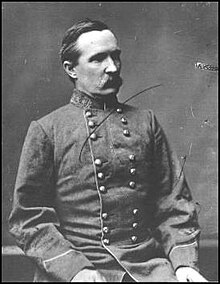

Henry Heth

Henry Heth | |

|---|---|

General Heth | |

| Nickname(s) | "Harry", "Jack" (in youth & at West Point) |

| Born | December 16, 1825 Black Heath, Virginia |

| Died | September 27, 1899 (aged 73) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1847–61 (USA) 1861–65 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations | George Pickett (cousin) |

Henry Heth (/ˈhiːθ/ not /ˈhɛθ/) (December 16, 1825 – September 27, 1899) was a career United States Army officer who became a Confederate general in the American Civil War.

He came to the notice of Robert E. Lee while serving briefly as his quartermaster, and was given a brigade in the Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia commanded by A. P. Hill, whose division he commanded when the latter was wounded at Chancellorsville. He is generally blamed for accidentally starting the Battle of Gettysburg by sending half his division into the town before the rest of the army was fully prepared. Later in the day, Confederate troops succeeded in routing two Union corps, but at a heavy cost in casualties. Heth continued to command his division during the remainder of the war and briefly took command of the Third Corps in April 1865 after the death of General Hill. Heth surrendered with the rest of Lee's army on April 9.

Early life

[edit]Henry Heth was born at Black Heath in Chesterfield County, Virginia, son of United States Navy Captain John Heth, and Margaret L. Pickett, sister of Robert Pickett, who was the father of Confederate general, George Pickett. He usually went by "Harry", the name also preferred by his grandfather, American Revolutionary War Colonel Henry Heth, who had established the Heth family in the coal business in the Virginia Colony after serving in the American Revolution. (The name Heth is pronounced like "Heath".) Henry Heth was born and raised in Virginia, as were both of his parents, all four of his grandparents and all eight of his great-grandparents. All sixteen of his great-great-grandparents came to Virginia from England, specifically from the rural areas of Hertfordshire, Hampshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire and Surrey.[1]

Heth was wounded at West Point in 1846 with a bayonet stab to his leg. He graduated from the United States Military Academy at the bottom of his class in 1847 (like his cousin George the year before). He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant and assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment. His antebellum career was served primarily in western posts, some as a quartermaster. He was serving as a first lieutenant in the 6th Infantry when John C. Symmes III refused a captaincy in the new 10th Infantry on March 3, 1855, and Heth was appointed in his place. He played a prominent role in the 1855 Battle of Ash Hollow (also known as the Harney Massacre due to the large number of Lakota women and children killed), leading a company of mounted infantry against the Lakota. In 1858, he created the first marksmanship manual for the Army.

Heth served at Camp Floyd during the Utah War. Camp Floyd had the largest concentration of US Troops at any post prior to the Civil War. While stationed in the desolate Utah Territory, he and others petitioned[2] the Freemason's Grand Lodge of Missouri to establish a Masonic Lodge in the Utah Territory. It was granted on March 6, 1859, for Rocky Mountain #205 under dispensation from Missouri; Heth served as the last Senior Warden of the first Masonic Lodge in Utah,[3] after which the Army was called away from Utah Territory to fight the American Civil War.

Civil War

[edit]

After the war began at Fort Sumter, Heth resigned from the U.S. Army and joined the Confederate States Army, where he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. His initial assignment was to muster and drill regiments of state militia in southwestern Virginia. In June, he was promoted to colonel. Born in Virginia's Tidewater region, Heth was unpopular with the mountain farmers and was known as a strict disciplinarian. In turn, Heth was frustrated by the illiteracy and lack of discipline of his men, as well as General John B. Floyd's actions as commanding officer in the region. Heth wrote of Floyd, "I soon discovered that my chief was as incapacitated for the work he had undertaken as I would have been to lead an Italian opera." Under Floyd, Heth led his regiment in the battles of Kessler's Cross Lanes and Carnifex Ferry. His brief service as General Robert E. Lee's quartermaster in the Virginia Provisional Army led to a close friendship between the two officers, Heth being one of the few generals whom Lee called by his first name. He spent the remainder of 1861 in the Kanawha Valley in western Virginia in the 5th and 45th Virginia Infantry regiments. He was promoted to brigadier general on January 6, 1862.

In the spring of 1862 Heth was in command of the "Army of the New River," (in actuality the 22nd and 45th Virginia Infantry regiments, with attached cavalry and artillery). Heth's diminutive force held off the forces of General Jacob D. Cox at Giles (County) Courthouse (May 10, 1862) and pursued the enemy to Lewisburg, where Heth was forced to withdraw (May 23, 1862). The actions were critical to keeping federal forces tied up and out of the southern Shenandoah Valley while Stonewall Jackson was conducting his own campaign 120 miles to the north. Despite the small size of his force, Heth submitted his reports as an army commander and had his regimental commanders write their own as "brigade" commanders, possibly assisting in the eventual promotion of Heth to major general.[4]

He was then sent west to the Department of East Tennessee, to serve under Edmund Kirby Smith. During the Kentucky Campaign, he was sent by Smith to take a division north from Lexington, Kentucky, to make a demonstration on Cincinnati. Although this caused a great commotion in the city's defenses, only a few skirmishes occurred.[5] Smith's portion of the army was spread too far north in Kentucky to consolidate with Bragg's portion in time for the Battle of Perryville. Bragg ordered the withdrawal of Confederate forces back to Tennessee, and Smith was subsequently transferred to the Trans-Mississippi Department, his forces again missing a vital battle at Stones River.

In March 1863, Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, then positioned at Fredericksburg, recalled Heth to Virginia to serve as a brigade commander in Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill's division. He fought in the Battle of Chancellorsville, showing aggressive, but misguided, qualities in his first large-scale combat, attacking without reserves against a Union force emerging from the Wilderness. Heth assumed command of Hill's division after Hill assumed corps command after Stonewall Jackson's wounding. Following the death of Jackson, Lee reorganized his army into three corps, promoting Hill to the Third Corps. Heth retained his division command and was promoted to major general on May 24, 1863.

Heth's division made history by inadvertently starting the Battle of Gettysburg. Marching east from Cashtown on July 1, 1863, Heth sent two brigades ahead in a reconnaissance in force. His memoirs referred to sending them in a search of shoes in Gettysburg, but some historians[who?] consider this an apocryphal story; they[who?] say Heth knew that Jubal A. Early had been in Gettysburg a few days earlier and any available shoes would have been taken at that time. They[who?] also consider sending two brigades on such a mission would have been wasteful. The brigades made contact with Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford and spread out into battle formation.

Lee had ordered A. P. Hill to avoid a general engagement with the enemy before he could assemble his full army, but Heth's actions had now rendered that order moot. They were engaged, and Union reinforcements started arriving quickly. Heth's decision to deploy his two brigades before the arrival of the rest of his division was an error as well; they were repulsed in hard fighting against an elite division of the Army of the Potomac's I Corps, including the famously tenacious Iron Brigade. After a lull in fighting, Heth brought two more brigades into the fray in the afternoon and the Union forces were driven back to Seminary Ridge, but principally because the XI Corps' right flank was crushed by Richard S. Ewell's corps coming in from the north. Finally, Heth attacked again in conjunction with the division of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes and the Union corps were routed, retreating back through town to Cemetery Hill, but Confederate losses were severe. Heth should have better coordinated his attack with the division of Maj. Gen. Dorsey Pender. Heth was wounded during the attack when a bullet struck him in the head. However, he was wearing a hat that was too large and stuffed with papers to make it fit. The papers probably deflected the bullet to avoid a fatal wound, but Heth was knocked unconscious and effectively out of the battle. Parts of his division, under the command of Brig. Gen. Johnston Pettigrew, saw more action two days later in Pickett's Charge, and Heth recovered enough to command during the retreat back to Virginia and the minor engagements of the fall of 1863.

Harry Heth commanded his division through the 1864 Overland Campaign. At the Battle of the Wilderness, his men were on the front line of A.P. Hill's corps, which blunted Union attacks on the Orange Plank Road. In the subsequent Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, his division was held primarily in the rear, and was positioned on the Confederate left flank at the Battles of North Anna and Cold Harbor. Heth also participated in the Siege of Petersburg, playing direct roles in the battles of Globe Tavern; Second Ream's Station; Peebles' Farm; Boydton Plank Road; and Hatcher's Run. Following the death of Gen. A.P. Hill on April 2, 1865, Heth briefly took over command of the Third Corps. Heth's troops, now led by Gen. John R. Cooke, were pushed back at the Battle of Sutherland's Station. Heth led the remainder of his troops in the Appomattox Campaign, fighting at Cumberland Church and retreating to Appomattox Court House, where he surrendered with Lee on April 9, 1865.

Postbellum years

[edit]

After the war, Heth worked in the insurance business and later served the government as a surveyor and in the Office of Indian Affairs. He died in Washington, D.C., and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.[6] Heth served as the first Commander of the Centennial Legion of Historic Military Commands when it was founded in 1876.[7]

In popular media

[edit]Heth was portrayed by Warren Burton in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara's novel, The Killer Angels.

Selected works

[edit]- A System of Target Practice (published in 1858)

- The Memoirs of Henry Heth (posthumous, 1974).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Virginia Lives: The Old Dominion Who's who - Page 450 by Richard Lee Morton · 1964

- ^ Goodwin, S. H. (1934). "Freemasonry in Utah : Rocky Mountain Lodge No. 205, A.F. & A.M., 1859-1861, Camp Floyd, the First Masonic Lodge in Utah" (PDF). Camp Floyd Historic Lodge No. 205 F. & A. M. Educational bulletin (Freemasons. Utah. Grand Lodge. Committee on Masonic Education and Instruction), no. 1, amplified. Salt Lake City. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Goodwin, S. H. (1934). "Freemasonry in Utah : Rocky Mountain Lodge No. 205, A.F. & A.M., 1859-1861, Camp Floyd, the First Masonic Lodge in Utah" (PDF). Camp Floyd Historic Lodge No. 205 F. & A. M. Educational bulletin (Freemasons. Utah. Grand Lodge. Committee on Masonic Education and Instruction), no. 1, amplified. Salt Lake City. pp. 3, 38. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, vol 12, Part 1, page 491-495 (Second Manassas)".

- ^ Noe, pp. 86-87.

- ^ "Death of General Heth". Vol. C, no. 229. Alexandria Gazette. Library of Congress - Chronicling America. September 27, 1899. p. 2. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ Centennial Legion of Historic Military Commands web site. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

References

[edit]- Berg, Andrew. "The Best Offense." Smithsonian Magazine, September 2005.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Noe, Kenneth W. Perryville: This Grand Havoc of Battle. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg, Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-2624-3.

- Krick, Robert K. The Unfulfilled Promise of Robert E. Lee’s Favorite Officer. www.historynet.com, June 6, 2018. http://www.historynet.com/unfulfilled-promise-robert-e-lees-favorite-officer.htm. Originally published in the January 2008 issue of America's Civil War.

External links

[edit]- Henry Heth in Encyclopedia Virginia

- "Henry Heth". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- 1825 births

- 1899 deaths

- People from Chesterfield County, Virginia

- Confederate States Army major generals

- American people of English descent

- United States Army officers

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- Members of the Aztec Club of 1847

- United States Military Academy alumni

- People of Virginia in the American Civil War

- Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia)

- American Freemasons

- Southern Historical Society