Trail of Tears

| Part of Indian removal | |

The Trail of Tears memorial at the New Echota Historic Site in Georgia, which honors the Cherokees who died on the Trail of Tears | |

| Date | 1830–1850 |

|---|---|

| Location | Southeastern United States and Indian Territory |

| Type | |

| Cause | Indian Removal Act signed by President Andrew Jackson |

| Motive |

|

| Target | The "Five Civilized Tribes" (Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, Choctaw) |

| Perpetrator | |

| Deaths | 13,200–16,700[a] |

| Displaced | 60,000 Indigenous Americans forcibly relocated to Indian Territory. |

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their enslaved African Americans[3] within that were ethnically cleansed by the United States government.[4]

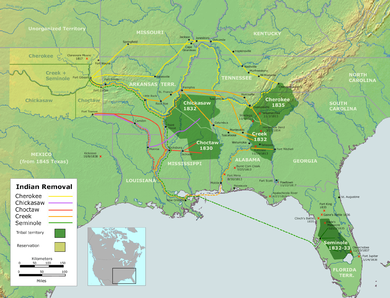

As part of Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States to newly designated Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830.[5][4][6] The Cherokee removal in 1838 was the last forced removal east of the Mississippi and was brought on by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush.[7] The relocated peoples suffered from exposure, disease, and starvation while en route to their newly designated Indian reserve. Thousands died from disease before reaching their destinations or shortly after.[8][9][10] A variety of scholars have classified the Trail of Tears as an example of the genocide of Native Americans;[11][b] others categorize it as ethnic cleansing.[32][c]

Overview

In 1830, a group of Indian nations collectively referred to as the "Five Civilized Tribes" (the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole nations), were living autonomously in what would later be termed the American Deep South. The process of cultural transformation from their traditional way of life towards a white American way of life as proposed by George Washington and Henry Knox was gaining momentum, especially among the Cherokee and Choctaw.[35][36]

American settlers had been pressuring the federal government to remove Indians from the Southeast; many settlers were encroaching on Indian lands, while others wanted more land made available to the settlers. Although the effort was vehemently opposed by some, including U.S. Congressman Davy Crockett of Tennessee, President Andrew Jackson was able to gain Congressional passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorized the government to extinguish any Indian title to land claims in the Southeast.

In 1831, the Choctaw became the first Nation to be removed, and their removal served as the model for all future relocations. After two wars, many Seminoles were removed in 1832. The Creek removal followed in 1834, the Chickasaw in 1837, and lastly the Cherokee in 1838.[37] Some managed to evade the removals, however, and remained in their ancestral homelands; some Choctaw still reside in Mississippi, Creek in Alabama and Florida, Cherokee in North Carolina, and Seminole in Florida. A small group of Seminole, fewer than 500, evaded forced removal; the modern Seminole Nation of Florida is descended from these individuals.[38] A number of non-Indians who lived with the nations, including over 4,000 slaves and others of African descent such as spouses or Freedmen,[39] also accompanied the Indians on the trek westward.[37] By 1837, 46,000 Indians from the southeastern states had been removed from their homelands, thereby opening 25 million acres (100,000 km2) for white settlement.[37][40] When the "Five Tribes" arrived in Indian Territory, "they followed their physical appropriation of Plains Indians' land with an erasure of their predecessor's history", and "perpetuated the idea that they had found an undeveloped 'wilderness" when they arrived" in an attempt to appeal to white American values by participating in the settler colonial process themselves. Other Indian nations, such as the Quapaws and Osages had moved to Indian Territory before the "Five Tribes" and saw them as intruders.[41]

Historical background

Before 1838, the fixed boundaries of these autonomous Indian nations, comprising large areas of the United States, were subject to continual cession and annexation, in part due to pressure from squatters and the threat of military force in the newly declared U.S. territories—federally administered regions whose boundaries supervened upon the Indian treaty claims. As these territories became U.S. states, state governments sought to dissolve the boundaries of the Indian nations within their borders, which were independent of state jurisdiction, and to expropriate the land therein. These pressures were exacerbated by U.S. population growth and the expansion of slavery in the South, with the rapid development of cotton cultivation in the uplands after the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney.[42]

Many people of the southeastern Indian nations had become economically integrated into the economy of the region. This included the plantation economy and the possession of slaves, who were also forcibly relocated during the removal.[42]

Prior to Jackson's presidency, removal policy was already in place and justified by the myth of the "Vanishing Indian".[43][44] Historian Jeffrey Ostler explains that "Scholars have exposed how the discourse of the vanishing Indian was an ideology that made declining Indigenous American populations seem to be an inevitable consequence of natural processes and so allowed Americans to evade moral responsibility for their destructive choices".[11] Despite the common association of Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears, ideas for Removal began prior to Jackson's presidency. Ostler explains, "A singular focus on Jackson obscures the fact that he did not invent the idea of removal…Months after the passage of the Removal Act, Jackson described the legislation as the 'happy consummation' of a policy 'pursued for nearly 30 years'".[11] James Fenimore Cooper was also a key component of the maintenance of the "vanishing Indian" myth. This vanishing narrative can be seen as existing prior to the Trail of Tears through Cooper's novel The Last of the Mohicans. Scholar and author Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz shows that:

Cooper has the last of the 'noble' and 'pure' Natives die off as nature would have it, with the 'last Mohican' handing the continent over to Hawkeye, the nativized settler, his adopted son ... Cooper had much to do with creating the US origin myth to which generations of historians have dedicated themselves, fortifying what historian Francis Jennings has described as "exclusion from the process of formation of American society and culture".[45]

Jackson's role

Although Jackson was not the sole, or original, architect of Removal policy, his contributions were influential in its trajectory. Jackson's support for the removal of the Indians began at least a decade before his presidency.[46] Indian removal was Jackson's top legislative priority upon taking office.[47] After being elected president, he wrote in his first address to Congress: "The emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land. But they should be distinctly informed that if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws. In return for their obedience as individuals they will without doubt be protected in the enjoyment of those possessions which they have improved by their industry".[45] The prioritization of American Indian removal and his violent past created a sense of restlessness among U.S. territories. During his presidency, "the United States made eighty-six treaties with twenty-six American Indian nations between New York and the Mississippi, all of them forcing land cessions, including removals".[45]

In a speech regarding Indian removal, Jackson said,[48]

It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.

The removals, conducted under both Presidents Jackson and Van Buren, followed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which provided the president with powers to exchange land with Indian nations and provide infrastructure improvements on the existing lands. The law also gave the president power to pay for transportation costs to the West, should the nations willingly choose to relocate. The law did not, however, allow the president to force Indian nations to move west without a mutually agreed-upon treaty.[49] Referring to the Indian Removal Act, Martin Van Buren, Jackson's vice president and successor, is quoted as saying "There was no measure, in the whole course of [Jackson's] administration, of which he was more exclusively the author than this."[47]

According to historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Jackson's intentions were outwardly violent. Dunbar-Ortiz claims that Jackson believed in "bleeding enemies to give them their senses" on his quest to "serve the goal of U.S. expansion". According to her, American Indians presented an obstacle to the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny, in his mind.[45][page needed] Throughout his military career, according to historian Amy H. Sturgis, "Jackson earned and emphasized his reputation as an 'Indian fighter', a man who believed creating fear in the native population was more desirable than cultivating friendship".[50] In a message to Congress on the eve of Indian Removal, December 6, 1830, Jackson wrote that removal "will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites." In this way, Sturgis has argued that Jackson demarcated the Indian population as an "obstacle" to national success.[50] Sturgis writes that Jackson's removal policies were met with pushback from respectable social figures and that "many leaders of Jacksonian reform movements were particularly disturbed by U.S policy toward American Indians".[50] Among these opponents were women's advocate and founder of the American Woman's Educational Association Catherine Beecher and politician Davy Crockett.[50]

Historian Francis Paul Prucha, on the other hand, writes that these assessments were put forward by Jackson's political opponents and that Jackson had benevolent intentions. According to him, Jackson's critics have been too harsh, if not wrong.[51] He states that Jackson never developed a doctrinaire anti-Indian attitude and that his dominant goal was to preserve the security and well-being of the United States and its Indian and white inhabitants.[52] Corroborating Prucha's interpretation, historian Robert V. Remini argues that Jackson never intended the "monstrous result" of his policy.[53] Remini argues further that had Jackson not orchestrated the removal of the "Five Civilized Tribes" from their ancestral homelands, they would have been totally wiped out.[54]

Treaty of New Echota

Jackson chose to continue with Indian removal, and negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, on December 29, 1835, which granted the Cherokee two years to move to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). The Chickasaws and Choctaws had readily accepted and signed treaties with the U.S. government, while the Creeks did so under coercion.[55]

The negotiation of the Treaty of New Echota was largely encouraged by Jackson, and it was signed by a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party, led by Cherokee leader Elias Boudinot.[56] However, the treaty was opposed by most of the Cherokee people, as it was not approved by the Cherokee National Council, and it was not signed by Principal Chief John Ross. The Cherokee National Council submitted a petition, signed by thousands of Cherokee citizens, urging Congress to void the agreement in February 1836.[57]

Despite this opposition, the Senate ratified the treaty in March 1836, and the Treaty of New Echota thus became the legal basis for the Trail of Tears. Only a fraction of the Cherokees left voluntarily. The U.S. government, with assistance from state militias, forced most of the remaining Cherokees west in 1838.[58][full citation needed]

The Cherokees were temporarily remanded in camps in eastern Tennessee. In November, the Cherokee were broken into groups of around 1,000 each and began the journey west. They endured heavy rains, snow, and freezing temperatures.[59]

When the Cherokee negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, they exchanged all their land east of the Mississippi for land in modern Oklahoma and a $5 million payment from the federal government. Many Cherokee felt betrayed that their leadership accepted the deal, and over 16,000 Cherokee signed a petition to prevent the passage of the treaty.

By the end of the decade in 1840, tens of thousands of Cherokee and other Indian nations had been removed from their land east of the Mississippi River. The Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chicksaw were also relocated under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. One Choctaw leader portrayed the removal as "A Trail of Tears and Deaths", a devastating event that removed most of the Indian population of the southeastern United States from their traditional homelands.[60]

Legal background

The establishment of the Indian Territory and the extinguishing of Indian land claims east of the Mississippi by the Indian Removal Act anticipated the U.S. Indian reservation system, which was imposed on remaining Indian lands later in the 19th century.[citation needed]

The statutory argument for Indian sovereignty persisted until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), that the Cherokee were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore not entitled to a hearing before the court.

In the years after the Indian Removal Act, the Cherokee filed several lawsuits regarding conflicts with the state of Georgia. Some of these cases reached the Supreme Court, the most influential being Worcester v. Georgia (1832).

Samuel Worcester and the group of white Christian missionaries he was in were convicted by Georgia law for living in Cherokee territory in the state of Georgia without a license in 1831.

Worcester was sentenced to prison for four years and appealed the ruling, arguing that this sentence violated treaties made between Indian nations and the United States federal government by imposing state laws on Cherokee lands. The Court ruled in Worcester's favor, declaring that the Cherokee Nation was subject only to federal law and that the Supremacy Clause barred legislative interference by the state of Georgia.

Chief Justice Marshall argued, "The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States."[61]

The Court did not ask federal marshals to carry out the decision.[62] Worcester thus imposed no obligations on Jackson; there was nothing for him to enforce,[63][64] although Jackson's' political enemies conspired to find evidence, to be used in the forthcoming political election, to claim that he would refuse to enforce the Worcester decision.[65] He feared that enforcement would lead to open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, which would compound the ongoing crisis in South Carolina and lead to a broader civil war. Instead, he vigorously negotiated a land exchange treaty with the Cherokee.[66][67]

After this, Jackson's political opponents Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, who supported the Worcester decision, became outraged by Jackson's alleged refusal to uphold Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia.[68] Author and political activist Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote an account of Cherokee assimilation into the American culture, declaring his support of the Worcester decision.[69]

At the time, members of individual Indian nations were not considered United States citizens.[70] While citizenship tests existed for Indians living in newly annexed areas before and after forced relocation, individual U.S. states did not recognize the Indian nations' land claims, only individual title under State law, and distinguished between the rights of white and non-white citizens, who often had limited standing in court; and Indian removal was carried out under U.S. military jurisdiction, often by state militias. As a result, individual Indians who could prove U.S. citizenship were nevertheless displaced from newly annexed areas.[42]

Choctaw removal

The Choctaw nation resided in large portions of what are now the U.S. states of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. After a series of treaties starting in 1801, the Choctaw nation was reduced to 11 million acres (45,000 km2). The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek ceded the remaining country to the United States and was ratified in early 1831. The removals were only agreed to after a provision in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek allowed some Choctaw to remain. The Choctaws were the first to sign a removal treaty presented by the federal government. President Jackson wanted strong negotiations with the Choctaws in Mississippi, and the Choctaws seemed much more cooperative than Andrew Jackson had imagined. The treaty provided that the United States would bear the expense of moving their homes and that they had to be removed within two and a half years of the signed treaty.[71] The chief of the Choctaw nation, George W. Harkins, wrote to the citizens of the United States before the removals were to commence:

It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and believing that your highly and well-improved minds would not be well entertained by the address of a Choctaw. But having determined to emigrate west of the Mississippi river this fall, I have thought proper in bidding you farewell to make a few remarks expressive of my views, and the feelings that actuate me on the subject of our removal... We as Choctaws rather chose to suffer and be free, than live under the degrading influence of laws, which our voice could not be heard in their formation.

— George W. Harkins, George W. Harkins to the American People[72]

United States Secretary of War Lewis Cass appointed George Gaines to manage the removals. Gaines decided to remove Choctaws in three phases starting in November 1831 and ending in 1833. The first groups met at Memphis and Vicksburg, where a harsh winter battered the emigrants with flash floods, sleet, and snow. Initially, the Choctaws were to be transported by wagon but floods halted them. With food running out, the residents of Vicksburg and Memphis were concerned. Five steamboats (the Walter Scott, the Brandywine, the Reindeer, the Talma, and the Cleopatra) would ferry Choctaws to their river-based destinations. The Memphis group traveled up the Arkansas for about 60 miles (100 km) to Arkansas Post. There the temperature stayed below freezing for almost a week with the rivers clogged with ice, so there could be no travel for weeks. Food rationing consisted of a handful of boiled corn, one turnip, and two cups of heated water per day. Forty government wagons were sent to Arkansas Post to transport them to Little Rock. When they reached Little Rock, a Choctaw chief referred to their trek as a "trail of tears and death".[73] The Vicksburg group was led by an incompetent guide and was lost in the Lake Providence swamps.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the French philosopher, witnessed the Choctaw removals while in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1831:

In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil but somber and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples.

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America[74]

Nearly 17,000 Choctaws made the move to what would be called Indian Territory and then later Oklahoma.[75] About 2,500–6,000 died along the trail of tears. Approximately 5,000–6,000 Choctaws remained in Mississippi in 1831 after the initial removal efforts.[76][77] The Choctaws who chose to remain in newly formed Mississippi were subject to legal conflict, harassment, and intimidation. The Choctaws "have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died".[77] The Choctaws in Mississippi were later reformed as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the removed Choctaws became the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Seminole resistance

The U.S. acquired Florida from Spain via the Adams–Onís Treaty and took possession in 1821. In 1832 the Seminoles were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Ocklawaha River. The Treaty of Payne's Landing called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable. They were to be settled on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek nation, who considered them deserters[full citation needed]; some of the Seminoles had been derived from Creek bands but also from other Indian nations. Those among the nation who once were members of Creek bands did not wish to move west to where they were certain that they would meet death for leaving the main band of Creek Indians. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833, that the new land was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the Indian nations and bands that resided on the reservation. The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.[78] On December 28, 1835, a group of Seminoles and blacks ambushed a U.S. Army company marching from Fort Brooke in Tampa to Fort King in Ocala, killing all but three of the 110 army troops. This came to be known as the Dade Massacre.

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the War Department for the loan of 500 muskets. Five hundred volunteers were mobilized under Brig. Gen. Richard K. Call. Indian war parties raided farms and settlements, and families fled to forts, large towns, or out of the territory altogether. A war party led by Osceola captured a Florida militia supply train, killing eight of its guards and wounding six others. Most of the goods taken were recovered by the militia in another fight a few days later. Sugar plantations along the Atlantic coast south of St. Augustine were destroyed, with many of the slaves on the plantations joining the Seminoles.[79]

Other war chiefs such as Halleck Tustenuggee, Jumper, and Black Seminoles Abraham and John Horse continued the Seminole resistance against the army. The war ended, after a full decade of fighting, in 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent about $20,000,000 on the war, ($631,448,276 today). Many Indians were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi; others retreated into the Everglades. In the end, the government gave up trying to subjugate the Seminole in their Everglades redoubts and left fewer than 500 Seminoles in peace. Other scholars state that at least several hundred Seminoles remained in the Everglades after the Seminole Wars.[80]

As a result of the Seminole Wars, the surviving Seminole band of the Everglades claims to be the only federally recognized Indian nation which never relinquished sovereignty or signed a peace treaty with the United States.[81]

In general the American people tended to view the Indian resistance as unwarranted. An article published by the Virginia Enquirer on January 26, 1836, called the "Hostilities of the Seminoles", assigned all the blame for the violence that came from the Seminole's resistance to the Seminoles themselves. The article accuses the Indians of not staying true to their word—the promises they supposedly made in the treaties and negotiations from the Indian Removal Act.[82]

Creek dissolution

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as William McIntosh and Chief Shelocta signed treaties that ceded more land to Georgia. The 1814 signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson signaled the end for the Creek Nation and for all Indians in the South.[83] Friendly Creek leaders, like Shelocta and Big Warrior, addressed Sharp Knife (the Indian nickname for Andrew Jackson) and reminded him that they keep the peace. Nevertheless, Jackson retorted that they did not "cut (Tecumseh's) throat" when they had the chance, so they must now cede Creek lands. Jackson also ignored Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent that restored sovereignty to Indians and their nations.

Jackson opened this first peace session by faintly acknowledging the help of the friendly Creeks. That done, he turned to the Red Sticks and admonished them for listening to evil counsel. For their crime, he said, the entire Creek Nation must pay. He demanded the equivalent of all expenses incurred by the United States in prosecuting the war, which by his calculation came to 23,000,000 acres (93,000 km2) of land.

— Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson[83]

Eventually, the Creek Confederacy enacted a law that made further land cessions a capital offense. Nevertheless, on February 12, 1825, McIntosh and other chiefs signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia.[84] After the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty, McIntosh was assassinated on April 30, 1825, by Creeks led by Menawa.

The Creek National Council, led by Opothle Yohola, protested to the United States that the Treaty of Indian Springs was fraudulent. President John Quincy Adams was sympathetic, and eventually, the treaty was nullified in a new agreement, the Treaty of Washington (1826).[85] The historian R. Douglas Hurt wrote: "The Creeks had accomplished what no Indian nation had ever done or would do again—achieve the annulment of a ratified treaty."[86] However, Governor George Troup of Georgia ignored the new treaty and began to forcibly remove the Indians under the terms of the earlier treaty. At first, President Adams attempted to intervene with federal troops, but Troup called out the militia, and Adams, fearful of a civil war, conceded. As he explained to his intimates, "The Indians are not worth going to war over."

Although the Creeks had been forced from Georgia, with many Lower Creeks moving to the Indian Territory, there were still about 20,000 Upper Creeks living in Alabama. However, the state moved to abolish tribal governments and extend state laws over the Creeks. Opothle Yohola appealed to the administration of President Andrew Jackson for protection from Alabama; when none was forthcoming, the Treaty of Cusseta was signed on March 24, 1832, which divided up Creek lands into individual allotments.[87] Creeks could either sell their allotments and receive funds to remove to the west, or stay in Alabama and submit to state laws. The Creeks were never given a fair chance to comply with the terms of the treaty, however. Rampant illegal settlement of their lands by Americans continued unabated with federal and state authorities unable or unwilling to do much to halt it. Further, as recently detailed by historian Billy Winn in his thorough chronicle of the events leading to removal, a variety of fraudulent schemes designed to cheat the Creeks out of their allotments, many of them organized by speculators operating out of Columbus, Georgia and Montgomery, Alabama, were perpetrated after the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta.[88] A portion of the beleaguered Creeks, many desperately poor and feeling abused and oppressed by their American neighbors, struck back by carrying out occasional raids on area farms and committing other isolated acts of violence. Escalating tensions erupted into open war with the United States after the destruction of the village of Roanoke, Georgia, located along the Chattahoochee River on the boundary between Creek and American territory, in May 1836. During the so-called "Creek War of 1836" Secretary of War Lewis Cass dispatched General Winfield Scott to end the violence by forcibly removing the Creeks to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. With the Indian Removal Act of 1830 it continued into 1835 and after as in 1836 over 15,000 Creeks were driven from their land for the last time. 3,500 of those 15,000 Creeks did not survive the trip to Oklahoma where they eventually settled.[60]

Chickasaw monetary removal

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 (equal to $14,700,000 today) for the westernmost part of the Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1837 and was led by John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at Memphis on July 4, 1837, with all of their assets—belongings, livestock, and slaves. Once across the Mississippi River, they followed routes previously established by the Choctaws and the Creeks. Once in Indian Territory, the Chickasaws merged with the Choctaw nation.

Cherokee forced relocation

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). Forcible removals began in May 1838 when General Winfield Scott received a final order from President Martin Van Buren to relocate the remaining Cherokees.[60] Approximately 4,000 Cherokees died in the ensuing trek to Oklahoma.[89] In the Cherokee language, the event is called nu na da ul tsun yi ("the place where they cried") or nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i (the trail where they cried). The Cherokee Trail of Tears resulted from the enforcement of the Treaty of New Echota, an agreement signed under the provisions of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which exchanged Indian land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River, but which was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people.[90]

There were significant changes in gender relations within the Cherokee Nation during the implementation of the Indian Removal Act during the 1830s. Cherokee historically operated on a matrilineal kinship system, where children belonged to the clan of their mother and their only relatives were those who could be traced through her. In addition to being matrilineal, Cherokees were also matrilocal.[91] According to the naturalist William Bartram, "Marriage gives no right to the husband over the property of his wife; and when they part, she keeps the children and property belonging to them."[92] In this way, the typical Cherokee family was structured in a way where the wife held possession to the property, house, and children.[93] However, during the 1820s and 1830s, "Cherokees [began adopting] the Anglo-American concept of power—a political system dominated by wealthy, highly acculturated men and supported by an ideology that made women … subordinate".[94]

The Treaty of New Echota was largely signed by men. While women were present at the rump council negotiating the treaty, they did not have a seat at the table to participate in the proceedings.[95] Historian Theda Perdue explains that "Cherokee women met in their own councils to discuss their own opinions" despite not being able to participate.[96] The inability for women to join in on the negotiation and signing of the Treaty of New Echota shows how the role of women changed dramatically within Cherokee Nation following colonial encroachment. For instance, Cherokee women played a significant role in the negotiation of land transactions as late as 1785, where they spoke at a treaty conference held at Hopewell, South Carolina to clarify and extend land cessions stemming from Cherokee support of the British in the American Revolution.[97]

The sparsely inhabited Cherokee lands were highly attractive to Georgian farmers experiencing population pressure, and illegal settlements resulted. Long-simmering tensions between Georgia and the Cherokee Nation were brought to a crisis by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1829, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush, the second gold rush in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure mounted to fulfill the Compact of 1802 in which the US Government promised to extinguish Indian land claims in the state of Georgia.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee lands in 1830, the matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Marshall court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national government—not state governments—had authority in Indian affairs. Worcester v Georgia is associated with Andrew Jackson's famous, though apocryphal, quote "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" In reality, this quote did not appear until 30 years after the incident and was first printed in a textbook authored by Jackson critic Horace Greeley.[67]

Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with South Carolina (i.e. the nullification crisis) and favored Cherokee relocation over civil war.[67] With the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the U.S. Congress had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty.

The final treaty, passed in Congress by a single vote, and signed by President Andrew Jackson, was imposed by his successor President Martin Van Buren. Van Buren allowed Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama an armed force of 7,000 militiamen, army regulars, and volunteers under General Winfield Scott to relocate about 13,000 Cherokees to Cleveland, Tennessee. After the initial roundup, the U.S. military oversaw the emigration to Oklahoma. Former Cherokee lands were immediately opened to settlement. Most of the deaths during the journey were caused by disease, malnutrition, and exposure during an unusually cold winter.[98]

In the winter of 1838 the Cherokee began the 1,000-mile (1,600 km) march with scant clothing and most on foot without shoes or moccasins. The march began in Red Clay, Tennessee, the location of the last Eastern capital of the Cherokee Nation. Because of the diseases, the Indians were not allowed to go into any towns or villages along the way; many times this meant traveling much farther to go around them.[1] After crossing Tennessee and Kentucky, they arrived at the Ohio River across from Golconda in southern Illinois about the 3rd of December 1838. Here the starving Indians were charged a dollar a head (equal to $28.61 today) to cross the river on "Berry's Ferry" which typically charged twelve cents, equal to $3.43 today. They were not allowed passage until the ferry had serviced all others wishing to cross and were forced to take shelter under "Mantle Rock", a shelter bluff on the Kentucky side, until "Berry had nothing better to do". Many died huddled together at Mantle Rock waiting to cross. Several Cherokee were murdered by locals. The Cherokee filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Government through the courthouse in Vienna, suing the government for $35 a head (equal to $1,001.44 today) to bury the murdered Cherokee.[1]

As they crossed southern Illinois, on December 26, Martin Davis, commissary agent for Moses Daniel's detachment, wrote:

There is the coldest weather in Illinois I ever experienced anywhere. The streams are all frozen over something like 8 or 12 inches [20 or 30 cm] thick. We are compelled to cut through the ice to get water for ourselves and animals. It snows here every two or three days at the fartherest. We are now camped in Mississippi [River] swamp 4 miles (6 km) from the river, and there is no possible chance of crossing the river for the numerous quantity of ice that comes floating down the river every day. We have only traveled 65 miles (105 km) on the last month, including the time spent at this place, which has been about three weeks. It is unknown when we shall cross the river....[99]

A volunteer soldier from Georgia who participated in the removal recounted:

I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.[100]

It eventually took almost three months to cross the 60 miles (97 kilometres) on land between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.[101] The trek through southern Illinois is where the Cherokee suffered most of their deaths. However a few years before forced removal, some Cherokee who opted to leave their homes voluntarily chose a water-based route through the Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It took only 21 days, but the Cherokee who were forcibly relocated were wary of water travel.[102]

Environmental researchers David Gaines and Jere Krakow outline the "context of the tragic Cherokee relocation" as one predicated on the difference between "Indian regard for the land, and its contrast with the Euro-Americans view of land as property".[103] This divergence in perspective on land, according to sociologists Gregory Hooks and Chad L. Smith, led to the homes of American Indian people "being donated and sold off" by the United States government to "promote the settlement and development of the West," with railroad developers, white settlers, land developers, and mining companies assuming ownership.[104] In American Indian society, according to Colville scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker, it caused "the loss of ancient connections to homelands and sacred sites," "the deaths of upward of 25 percent of those on the trail" and "the loss of life-sustaining livestock and crops."[105]

Dina Gilio-Whitaker draws on research by Choctaw and Chippewa historian Clara Sue Kidwell to show the relationship between the Trail of Tears and a negative impact on the environment. In tracking the environmental changes of the southeastern tribes who relocated to new lands across the Trail of Tears, Kidwell finds that "prior to removal the tribes had already begun adapting to a cash-based, private property economic system with their adoption of many European customs (including the practice of slave owning), after their move west they had become more deeply entrenched into the American economic system with the discovery of coal deposits and the western expansion of the railroads on and through their lands. So while they adapted to their new environments, their relationship to land would change to fit the needs of an imposed capitalist system".[105] Cherokee ethnobotanist Clint Carroll illustrates how this imposed capitalist system altered Cherokee efforts to protect traditional medicinal plants during relocation, saying that "these changes have resulted in contrasting land management paradigms, rooted in the language of 'resource-based' versus 'relationship-based' approaches, a binary imposed on tribal governments by the Bureau of Indian Affairs through their historically paternalistic relationship".[105] This shift in land management as a function of removal had negative environmental ramifications such as solidifying "a deeply entrenched bureaucratic structure that still drives much of the federal-tribal relationship and determines how tribal governments use their lands, sometimes in ways that contribute to climate change and, in extreme cases, ways that lead to human rights abuses".[105]

In addition to a physical relocation, American Indian removal and the Trail of Tears had social and cultural effects as American Indians were forced "to contemplate abandonment of their native land. To the Cherokees life was a part of the land. Every rock, every tree, every place had a spirit. And the spirit was central to the tribal lifeway. To many, the thought of loss of place was a thought of loss of self, loss of Cherokeeness, and a loss of life- way".[106] This cultural shift is characterized by Gilio-Whitaker as "environmental deprivation," a concept that "relates to historical processes of land and resource dispossession calculated to bring about the destruction of Indigenous Americans' lives and cultures. Environmental deprivation in this sense refers to actions by settlers and settler governments that are designed to block Native peoples' access to life-giving and culture-affirming resources".[105] The separation of American Indian people from their land lead to the loss of cultural knowledge and practices, as described by scholar Rachel Robison-Greene, who finds the "legacy of fifteenth-century European colonial domination" led to "Indigenous knowledge and perspectives" being "ignored and denigrated by the vast majority of social, physical, biological and agricultural scientists, and governments using colonial powers to exploit Indigenous resources".[107] Indigenous cultural and intellectual contribution to "environmental issues" in the form of a "rich history, cultural customs, and practical wisdom regarding sustainable environmental practices" can be lost because of Indigenous removal and the Trail of Tears, according to Greene.

Removed Cherokees initially settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma. When signing the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 Major Ridge said "I have signed my death warrant." The resulting political turmoil led to the killings of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot; of the leaders of the Treaty Party, only Stand Watie escaped death.[108] The population of the Cherokee Nation eventually rebounded, and today the Cherokees are the largest American Indian group in the United States.[109]

There were some exceptions to removal. Approximately 100 Cherokees evaded the U.S. soldiers and lived off the land in Georgia and other states. Those Cherokees who lived on private, individually owned lands (rather than communally owned tribal land) were not subject to removal. In North Carolina, about 400 Cherokees, sometimes referred to as the Oconaluftee Cherokee due to their settlement near to the river of the same name, lived on land in the Great Smoky Mountains owned by a white man named William Holland Thomas (who had been adopted by Cherokees as a boy), and were thus not subject to removal. Added to this were some 200 Cherokee from the Nantahala area allowed to stay in the Qualla Boundary after assisting the U.S. Army in hunting down and capturing the family of the old prophet, Tsali, who was executed by a firing squad as were most of his family. These North Carolina Cherokees became the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation.

A local newspaper, the Highland Messenger, said July 24, 1840, "that between nine hundred and a thousand of these deluded beings … are still hovering about the homes of their fathers, in the counties of Macon and Cherokee" and "that they are a great annoyance to the citizens" who wanted to buy land there believing the Cherokee were gone; the newspaper reported that President Martin Van Buren said "they … are, in his opinion, free to go or stay.'[110]

Several Cherokee speakers throughout history offered first-hand accounts of the events of the Trail of Tears as well as provided insight into its lasting effects. Elias Budinot, Major Ridge, Speckled Snake, John Ross, and Richard Taylor were all notable Cherokee orators during the 19th century who used the speech as a form of resistance against the U.S. government. John Ross, the Cherokee Chief from 1828 to 1866, and Major Ridge embarked on a speaking tour within the Cherokee Nation itself in hopes of strengthening a sense of unity amongst the tribal members.[111] Tribal unity was a central tenet to Cherokee resistance, with Ross stating in his council address: "'Much…depends on our unity of sentiment and firmness of action, in maintaining those sacred rights which we have ever enjoyed'".[111] Cherokee speeches like this were made even more important because the state of Georgia made it illegal for members of American Indian tribes to both speak to an all-white court and convince other Indian tribal members not to move.[111]

Another influential Cherokee figure was Cherokee writer John Ridge, son of Major Ridge, who wrote four articles using the pseudonym "Socrates". His works were published in the Cherokee Phoenix, the nation's newspaper. The choice of pseudonym, according to literary scholar Kelly Wisecup, "...facilitated a rhetorical structure that created not only a public persona recognizable to the Phoenix's multiple readerships but also a public character who argued forcefully that white readers should respect Cherokee rights and claims".[112] The main focal points of Ridge's articles critiqued the perceived hypocrisy of the U.S. government, colonial history, and the events leading up to the Trail of Tears, using excerpts from American and European history and literature.[112]

Eastern Cherokee Restitution

The United States Court of Claims ruled in favor of the Eastern Cherokee Nation's claim against the U.S. on May 18, 1905. This resulted in the appropriation of $1 million (equal to $27,438,023.04 today) to the Nation's eligible individuals and families. Interior Department employee Guion Miller created a list using several rolls and applications to verify tribal enrollment for the distribution of funds, known as the Guion Miller Roll. The applications received documented over 125,000 individuals; the court approved more than 30,000 individuals to share in the funds.[113][page needed]

Statistics

| Nation | Population before removal | Treaty and year | Major emigration | Total removed | Number remaining | Deaths during removal | Deaths from warfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choctaw | 19,554[114]

+ white citizens of the Choctaw Nation + 500 Black slaves |

Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830) | 1831–1836 | 15,000[75] | 5,000–6,000[115][116][117] | 2,000–4,000+ (cholera) | none |

| Creek (Muscogee) | 22,700 + 900 Black slaves[118] | Cusseta (1832) | 1834–1837 | 19,600[119] | 744[120] | 3,500–4,500 (disease after removal)[121][122] | Unknown (Creek War of 1836) |

| Chickasaw | 4,914 + 1,156 Black slaves[123] | Pontotoc Creek (1832) | 1837–1847 | 4,600[120] | 400[120] | 500–800 | none |

| Cherokee | 16,542 + 201 married white + 1,592 Black slaves[124] | New Echota (1835) | 1836–1838 | 16,000,[125] but according to Indian Affairs report from 1841 there were 25,911 Cherokees already removed to Indian Territory.[120] | 1,500 | 4,000–8,000[126][127][122][45]: 113 | none |

| Seminole | 3,700–5,000[128] + fugitive slaves | Payne's Landing (1832) | 1832–1842 | 2,833[129]–4,000[130] | 250[129]–500[131] or 575[120] | up to 5,500 (Second Seminole War) |

Legacy

Terminology

The events have sometimes been referred to as "death marches", in particular when referring to the Cherokee march across Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri in 1838.[42][132][133]

Indians who had the means initially provided for their own removal. Contingents that were led by conductors from the U.S. Army included those led by Edward Deas, who was claimed to be a sympathizer for the Cherokee plight.[citation needed] The largest death toll from the Cherokee forced relocation comes from the period after the May 23, 1838 deadline. This was at the point when the remaining Cherokee were rounded up into camps and placed into large groups, often over 700 in size. Communicable diseases spread quickly through these closely quartered groups, killing many. These groups were among the last to move, but following the same routes the others had taken; the areas they were going through had been depleted of supplies due to the vast numbers that had gone before them. The marchers were subject to extortion and violence along the route. In addition, these final contingents were forced to set out during the hottest and coldest months of the year, killing many. Exposure to the elements, disease, starvation, harassment by local frontiersmen, and insufficient rations similarly killed up to one-third of the Choctaw and other nations on the march.[76] There exists some debate among historians and the affected nations as to whether the term "Trail of Tears" should be used to refer to the entire history of forced relocations from the Eastern United States into Indian Territory, to the relocations of specifically the Five Civilized Tribes, to the route of the march, or to specific marches in which the remaining holdouts from each area were rounded up.[citation needed]

Classification debate

There is debate among historians about how the Trail of Tears should be classified. Some historians classify the events as a form of ethnic cleansing;[134][135][32] others refer to it as genocide.[105][11][45]

Historian and biographer Robert V. Remini wrote that Jackson's policy on Native Americans was based on good intentions. He writes: "Jackson fully expected the Indians to thrive in their new surroundings, educate their children, acquire the skills of white civilization so as to improve their living conditions, and become citizens of the United States. Removal, in his mind, would provide all these blessings....Jackson genuinely believed that what he had accomplished rescued these people from inevitable annihilation."[136] Historian Sean Wilentz writes that some critics who label Indian removal as genocide view Jacksonian democracy as a "momentous transition from the ethical community upheld by antiremoval men", and says this view is a caricature of US history that "turns tragedy into melodrama, exaggerates parts at the expense of the whole, and sacrifices nuance for sharpness".[137][138] Historian Donald B. Cole, too, argues that it is difficult to find evidence of a conscious desire for genocide in Jackson's policy on Native Americans, but dismisses the idea that Jackson was motivated by the welfare of Native Americans.[138] Colonial historian Daniel Blake Smith disagrees with the usage of the term genocide, adding that "no one wanted, let alone planned for, Cherokees to die in the forced removal out West".[139]

Historian Justin D. Murphy argues that:

Although the “Trail of Tears” was tragic, it does not quite meet the standard of genocide, and the extent to which tribes were allowed to retain their identity, albeit by removal, does not quite meet the standard of cultural genocide".[140]

In contrast, some scholars have debated that the Trail of Tears was a genocidal act.[11][32][134] Historian Jeffrey Ostler argues that the threat of genocide was used to ensure Natives' compliance with removal policies,[11][141]: 1 and concludes that, "In its outcome and in the means used to gain compliance, the policy had genocidal dimensions."[141] Patrick Wolfe argues that settler colonialism and genocide are interrelated but should be distinguished from each other, writing that settler colonialism is "more than the summary liquidation of Indigenous people, though it includes that."[142] Wolfe describes the assimilation of Indigenous people who escaped relocation (and particularly their abandonment of collectivity) as a form of cultural genocide, though he emphasises that cultural genocide is “the real thing” in that it resulted in large numbers of deaths. The Trail of Tears was thus a settler-colonial replacement of Indigenous people and culture in addition to a genocidal mass-killing according to Wolfe.[142]: 1 [142]: 2 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz describes the policy as genocide, saying: "The fledgling United States government's method of dealing with native people—a process which then included systematic genocide, property theft, and total subjugation—reached its nadir in 1830 under the federal policy of President Andrew Jackson."[45] Mankiller emphasises that Jackson's policies were the natural extension of much earlier genocidal policies toward Native Americans established through territorial expansion during the Jefferson administration.[45]

Dina Gilio-Whitaker, in As Long as Grass Grows, describes the Trail of Tears and the Diné long walk as structural genocide, because they destroyed Native relations to land, one another, and nonhuman beings which imperiled their culture, life, and history. According to her, these are ongoing actions that constitute both cultural and physical genocide.[105]: 35–51 [143]

Landmarks and commemorations

In 1987, about 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of trails were authorized by federal law to mark the removal of 17 detachments of the Cherokee people.[144] Called the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, it traverses portions of nine states and includes land and water routes.[145]

Trail of Tears outdoor historical drama, Unto These Hills

A historical drama based on the Trail of Tears, Unto These Hills written by Kermit Hunter, has sold over five million tickets for its performances since its opening on July 1, 1950, both touring and at the outdoor Mountainside Theater of the Cherokee Historical Association in Cherokee, North Carolina.[146][147]

Remember the Removal bike ride

A regular event, the "Remember the Removal Bike Ride," entails six cyclists from the Cherokee Nation to ride over 950 miles while retracing the same path that their ancestors took. The cyclists, who average about 60 miles a day, start their journey in the former capital of the Cherokee Nation, New Echota, Georgia, and finish in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.[148] In June 2024, Shawna Baker, justice of the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court was a mentor cyclist on the 40th commemorative ride.[149]

Commemorative medallion

Cherokee artist Troy Anderson was commissioned to design the Cherokee Trail of Tears Sesquicentennial Commemorative Medallion. The falling-tear medallion shows a seven-pointed star, the symbol of the seven clans of the Cherokees.[150]

In literature and oral history

- Family Stories From the Trail of Tears is a collection edited by Lorrie Montiero and transcribed by Grant Foreman, taken from the Indian-Pioneer History Collection[151]

- Johnny Cash played in the 1970 NET Playhouse dramatization of The Trail of Tears.[152] He also recorded the reminiscences of a participant in the removal of the Cherokee.[153]

- Walking the Trail (1991) is a book by Jerry Ellis describing his 900-mile walk retracing of the Trail of Tears in reverse

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, a Cherokee scholar and poet, was a more contemporary figure who wrote a poem titled "Trail of Tears" that enshrined the devastation faced by the Cherokee nation that still permeates Indigenous conscience today:

From the homes their fathers made // From the graves the tall trees shade // For the sake of greed and gold, // The Cherokees were forced to go // To a land they did not know; // And Father Time or wisdom old // Cannot erase, through endless years // The memory of the trail of tears.

Notes

- ^

- Cherokee - 4,000

- Creek and Seminole in Second Seminole War (1835–1842) - 3,000

- Chickasaw - 3,500

- Choctaw - 2,500–6,000

- ^

- Political scientist Michael Rogin – "To face responsibility for specific killings might have led to efforts to stop it; to avoid individual deaths turned Indian removal into a theory of genocide."[12]

- Indigenous studies scholar Nicky Michael and historian Beverly Jean Smith – "Over one-fourth died on the forced death marches of the 1830s. By any United Nations standard, these actions can be equated with genocide and ethnic cleansing."[13]

- Historian Jim Piecuch argues that the Trail of Tears constitutes one tool in the genocide of Native Americans over the three centuries since the beginning of colonization in north America.[14]

- Political scientist Andrew R. Basso – "The Cherokee Trail of Tears should be understood within the context of colonial genocide in the Americas. This is yet another chapter of colonial forces acting against an indigenous group in order to secure rich and fertile lands, resources, and living spaces."[15]

- Political scientist Barbara Harff – "One of the most enduring and abhorrent problems of the world is genocide, which is neither particular to a specific race, class, or nation, nor rooted in any one ethnocentric view of the world. […] Often democratic institutions are cited as safeguards against mass excesses. In view of the treatment of Amerindians by agents of the U.S. government, this view is unwarranted. For example, the thousands of Cherokees who died during the Trail of Tears (Cherokee Indians were forced to march in 1838-1839 from Appalachia to Oklahoma) testify that even a democratic system may tum against its people."[16]

- Legal scholar Rennard Strickland – "There were, of course, great and tragic Indian massacres and bitter exoduses, illegal even under the laws of war. We know these acts of genocide by place names - Sand Creek, the Battle of Washita, Wounded Knee - and by their tragic poetic codes - the Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, the Cheyenne Autumn. But ... genocidal objectives have been carried out under color of law - in de Tocqueville's phrase, "legally, philanthropically, without shedding blood, and without violating a single great principle of morality in the eyes of the word." These were legally enacted policies whereby a way of life, a culture, was deliberately obliterated. As the great Indian orator Dragging Canoe concluded, "Whole Indian Nations have melted away like balls of snow in the sun leaving scarcely a name except as imperfectly recorded by their destroyers"."[17]

- Legal scholars Christopher Turner and Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond reiterate Strickland's assessment.[18]

- Attorney Maria Conversa – "The theft of ancestral tribal lands, the genocide of tribal members, public hostility towards Native peoples, and irreversible oppression--these are the realities that every indigenous person has had to face because of colonization. By recognizing and respecting the Muscogee Creek Nation's authority to criminally sentence its own members, the United States Supreme Court could have taken a small step towards righting these wrongs."[19]

- Genocide education scholar Thomas Keefe – "The preparation (Stage 7) for genocide, specifically the transfer of population that "Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part" as stated in Article II of the UNCPPCG is clear in the Trail of Tears and other deportations of Native American populations from land seized for the benefit of European-American populations."[20]

- Historian David Stannard and ethnic studies scholar Ward Churchill have both identified the trail of tears as part of the United States history of genocidal actions against indigenous nations.[21][22]

- Sociologist James V. Fenelon and historian Clifford E. Trafzer – "Instead the national government and its leaders have offered a systemic denial of genocide, the occurrence of which would be contrary to the principles of a democratic and just society. "Denial of massive death counts is common among those whose forefathers were the perpetrators of the genocide" (Stannard, 1992, p. 152) with motives of protecting "the moral reputations of those people and that country responsible," including some scholars. It took 50 years of scholarly debate for the academy to recognize well-documented genocides of the Indian removals in the 1830s, including the Cherokee Trail of Tears, as with other nations of the "Five Civilized" southeastern tribes."[23]

- Sociologist Benjamin P. Bowser, psychologist Carol O. Word, and Kate Shaw – "There was a pattern to Indian genocide. One-by-one, each Native state was defeated militarily; successive Native generations fought and were defeated as well. As settlers became more numerous and stronger militarily, Indians became fewer and weaker militarily. In one Indian nation after the other, resistance eventually collapsed due to the death toll from violence. Then, survivors were displaced from their ancestral lands, which had sustained them for generations. […] Starting in 1830, surviving Native people, mostly Cherokee, in the Eastern US were ordered by President Andrew Jackson to march up to two thousand miles and to cross the Mississippi River to settle in Oklahoma. Thousands died on the Trail of Tears. This pattern of defeat, displacement, and victimization repeated itself in the American West. From this history, Native Americans were victims of all five Lemkin specified genocidal acts."[24]

- Sociologist and historian Vahakn Dadrian lists the expulsion of the Cherokee as an example of utilitarian genocide, stating "the expulsion and decimation of the Cherokee Indians from the territories of the State of Georgia is symbolic of the pattern of perpetration inflicted upon the American Indian by Whites in North America."[25]

- Genocide scholar Adam Jones – "Forced relocations of Indian populations often took the form of genocidal death marches, most infamously the "Trails of Tears" of the Cherokee and Navajo nations, which killed between 20 and 40 percent of the targeted populations en route. The barren "tribal reservations" to which survivors were consigned exacted their own grievous toll through malnutrition and disease."[26]

- Cherokee politician Bill John Baker – "this ruthless [Indian Removal Act] policy subjected 46,000 Indians—to a forced migration under punishing conditions […] amounted to genocide, the ethnic cleansing of men, women and children, motivated by racial hatred and greed, and carried out through sadism and violence."[27]

- Sociologist and psychologist Laurence French wrote that the trail of tears was at least a campaign of cultural genocide.[28]

- Cultural studies scholar Melissa Slocum – "Rarely is the conversation about the impact of genocide on today’s generations or the overall steps that lead to genocide. As well, most curricula in the education system, from kindergarten up through to college, does not discuss in detail American Indian genocide beyond possibly a quick one-day mention of the Cherokee Trail of Tears."[29]

- English and literary scholar Thir Bahadur Budhathoki – "On the basis of the basic concept of genocide as propounded by Rephael Lemkin, the definitions of the UN Convention and other genocide scholars, sociological perspective of genocide-modernity nexus and the philosophical understanding of such crime as an evil in its worst possible form, the fictional representation of the entire process of Cherokee removal including its antecedents and consequences represented in these novels, is genocidal in nature. However, the American government, that mostly represents the perpetrators of the process, and the Euro-American culture of the United States considered as the mainstream culture, have not acknowledged the Native American tragedy as genocide."[30]

- Muscogee Nation Historic and Cultural Preservation Manager Rae Lynn Butler – "really was about extinguishing a race of people"; Archivist at the Cherokee Heritage Center Jerrid Miller – "The Trail of Tears was outright genocide".[31]

- ^ Ethnic cleansing is a term dating from the 20th Century with roots in 1940s Nazi Germany, coming into wide usage starting in 1988.[33] Genocide is a term that came into use in 1944 from Raphael Lemkin's book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.[34]

See also

- Long Walk of the Navajo, a later forced removal

- Cupeño trail of tears, the last native forced removal

- California Genocide

- Northern Cheyenne Exodus

- Potawatomi Trail of Death

- Timeline of Cherokee removal

- Steamboat Monmouth disaster

References

- ^ a b c Report. Illinois General Assembly. Vol. HJR0142.

- ^ Crepelle, Adam (2021). "Lies, Damn Lies, and Federal Indian Law: The Ethics of Citing Racist Precedent in Contemporary Federal Indian Law" (PDF). N.y.u. Review of Law & Social Change. 44: 565. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Littlefield, Daniel F. Jr. The Cherokee Freedmen: From Emancipation to American Citizenship. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978, p. 68

- ^ a b Minges, Patrick (1998). "Beneath the Underdog: Race, Religion, and the Trail of Tears". US Data Repository. Archived from the original on October 11, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ "Indian removal". PBS. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Alaina E. (2021). I've Been Here All The While: Black Freedom on Native Land. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780812253030.

- ^ Inskeep, Steve (2015). Jacksonland: President Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-1-59420-556-9.

- ^ Thornton 1991, pp. 75–93; Prucha 1984, p. 241; Ehle 2011, pp. 291–292

- ^ "A Brief History of the Trail of Tears". www.cherokee.org. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ "Native Americans". Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvgc629z. ISBN 978-0-300-21812-1. JSTOR j.ctvgc629z. S2CID 166826195.

- ^ Lutz, Regan A. (June 1995). West of Eden: The Historiography of the Trail of Tears (PhD). University of Toledo. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Michael, Smith & Lowe 2021, p. 27.

- ^ Piecuch, Jim (7 December 2014). "Perspective 1: three Centuries of Genocide". In Bartrop, Paul R.; Jacobs, Steven Leonard (eds.). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693639.

- ^ Basso, Andrew R. (6 March 2016). "Towards a Theory of Displacement Atrocities: The Cherokee Trail of Tears, The Herero Genocide, and The Pontic Greek Genocide". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 10 (1): 5–29 [15]. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.10.1.1297.

- ^ Harff, Barbara (1987). "The Etiology of Genocides". In Wallimann, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N. (eds.). The Age of Genocide: Etiology and Case Studies of Mass Death. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 41.

- ^ Strickland, Rennard (1986). "Genocide-at-Law: An Historic and Contemporary View of the North American Experience". University of Kansas Law Review. 713: 719.

- ^ Tennant, Christopher C.; Turpel, Mary Ellen (1990). "A Case Study of Indigenous Peoples: Genocide, Ethnocide and Self-determination". Nordic Journal of International Law. 287 (4): 287–319 [296–297]. doi:10.1163/157181090X00387.

- ^ Conversa, Maria (2021). "Righting the Wrongs of Native American Removal and Advocating for Tribal Recognition: A Binding Promise, The Trail of Tears, and the Philosophy of Restorative Justice". UIC Law Review. 933. University of Illinois Chicago: 4, 13.

- ^ Keefe, Thomas E. (13–14 April 2019). Native American Genocide: Realities and Denials. First International Conference of the Center for Holocaust, Genocide & Human Rights Studies, University of North Carolina. Charlotte. p. 21.

- ^ Lewy, Guenter (9 November 2007). "Can there be genocide without the intent to commit genocide?". Journal of Genocide Research. 9 (4): 661–674 [669]. doi:10.1080/14623520701644457.

- ^ MacDonald, David B. (2015). "Canada's history wars: indigenous genocide and public memory in the United States, Australia and Canada". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 411–431 [415]. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096583.

- ^ Fenelon, James V.; Trafzer, Clifford E. (2014). "From Colonialism to Denial of California Genocide to Misrepresentations: Special Issue on Indigenous Struggles in the Americas". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (3): 3–29 [16]. doi:10.1177/0002764213495045.

- ^ Bowser, Benjamin P.; Word, Carl O.; Shaw, Kate (2021). "Ongoing Genocides and the Need for Healing: The Cases of Native and African Americans". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 15 (3): 83–99 [86]. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.15.3.1785.

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1975). "A Typology of Genocide". International Review of Modern Sociology. 5 (2): 201–212 [209]. JSTOR 41421531.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2006). "The conquest of the Americas". Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-203-34744-7.

- ^ Bracey, Earnest N. (2021). "Andrew Jackson, Black American Slavery, and the Trail of Tears: A Critical Analysis". Dialogue and Universalism. 31 (1): 119–138 [128]. doi:10.5840/du20213118.

- ^ French, Laurence (June 1978). "The Death of a Nation". American Indian Journal. 4 (6): 2–9 [2].

- ^ Slocum, Melissa Michal (2018). "There Is No Question of American Indian Genocide". Transmotion. 4 (2): 1– 30 [4]. doi:10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.651.

- ^ Budhathoki, Thir Bahadur (December 2013). Literary Rendition of Genocide in Cherokee Fiction (MPhil). Tribhuvan University. p. 89.

- ^ Martin Rogers, Janna Lynell (July 2019). Decolonizing Cherokee History 1790-1830s: American Indian Holocaust, Genocidal Resistance, and Survival (MA). Oklahoma State University. p. 63.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Gary Clayton (2014). Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-8061-4508-2.

- ^ Safire, William (March 14, 1993). "On Language: Ethnic Cleansing". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Lemkin, Raphael (2005) [1944]. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress. The Lawbook Exchange. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8. Retrieved June 24, 2024. Originally published in 1944 by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Perdue, Theda (2003). "Chapter 2 'Both White and Red'". Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. University of Georgia Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-8203-2731-X.

- ^ "The Trail of Tears". PBS. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Indian removal 1814 - 1858". PBS. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- ^ Gannon, Michael, ed. (1996). The new history of Florida. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. pp. 183–206. ISBN 0813014158. OCLC 32469459.

- ^ Smith, Ryan P. "How Native American Slaveholders Complicate the Trail of Tears Narrative". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Carter 1976, p. 232.

- ^ Roberts, Alaina E. (2021). I've Been Here All The While: Black Freedom on Native Land. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 12–15. ISBN 9780812253030.

- ^ a b c d Jahoda, Gloria (1975). Trail of Tears: The Story of the American Indian Removal 1813-1855. Wings Books. ISBN 978-0-517-14677-4.

- ^ O'Brien, Jean (2010). Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1452915258.

- ^ Berkhofer, Robert (1979). The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian, from Columbus to the Present. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 9780394727943.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-0040-3. OCLC 868199534.

- ^ Wallace, Anthony (2011). The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9781429934275.

- ^ a b Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743797.

- ^ "President Andrew Jackson's Message to Congress 'On Indian Removal' (1830)". National Archives. June 25, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ Morris, Michael (2007). "Georgia and the Conversation over Indian Removal". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 91 (4): 403–423. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Sturgis, Amy H. (2007). The Trail of Tears and Indian removal. Greenwood Press. pp. 33, 40, 41. ISBN 978-0-313-05620-8. OCLC 181203333.

- ^ Prucha, Francis Paul (1969). "Andrew Jackson's Indian Policy: A Reassessment". The Journal of American History. 56 (3): 527–539. doi:10.2307/1904204. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 1904204.

- ^ Boyd, Kelly (1999). Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing. Taylor & Francis. p. 967. ISBN 978-1-884964-33-6.

- ^ Remini 2001, p. 270.

- ^ Remini, Robert V. (1998-04-10). Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-8018-5913-7.

They are gone, wiped out. And there are other such tribes. President Jackson and his Democratic friends warned the Cherokees and the other southern tribes that extinction would be their fate if they refused to remove.

- ^ Feller, Daniel (October 4, 2016). "Andrew Jackson: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center. Archived from the original on July 1, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Clair, Robin Patric (September 1997). "Organizing silence: Silence as voice and voice as silence in the narrative exploration of the treaty of New Echota". Western Journal of Communication. 61 (3): 315–337. doi:10.1080/10570319709374580. ISSN 1057-0314.

- ^ Carroll, Clint (May 15, 2015). "Shaping New Homelands: Landscapes of Removal and Renewal". Roots of Our Renewal: Ethnobotany and Cherokee Environmental Governance. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 57–82. doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816690893.003.0003. ISBN 9780816690893. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ River, Charles. The Trail of Tears: Forced Removal of Five Civilized Tribes.

- ^ Perdue, Theda; Green, Michael D. (2008). The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. Viking. p. 137. ISBN 9780670031504.

- ^ a b c "Trail of Tears". History Channel. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ Coates, Julia. Trail of Tears.

"Worcester v. Georgia". Oyez. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2017. - ^ Berutti 1992, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Banner, Stuart (2005). How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 218–224.

- ^ Norgren, Jill (2004). The Cherokee Cases: Two Landmark Federal Decisions in the Fight for Sovereignty. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 122–130.

- ^ Ellis, Richard E. (1987). The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights and the Nullification Crisis. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-802084-4.

- ^ Gilbert, Joan (1996). "The Cherokee Home in the East". The Trail of Tears Across Missouri. University of Missouri Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8262-1063-5.

- ^ a b c Miles, Edwin A (November 1973). "After John Marshall's Decision: Worcester v Georgia and the Nullification Crisis". The Journal of Southern History. 39 (4): 519–544. doi:10.2307/2205966. JSTOR 2205966.

- ^ Cave, Alfred A. (Winter 2003). "Abuse of Power: Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830". The Historian. 65 (6): 1347–1350. doi:10.1111/j.0018-2370.2003.00055.x. JSTOR 24452618. S2CID 144157296.

- ^ Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2009). Genocide and International Justice. Infobase Publishing. pp. 128–131. ISBN 978-0816073108. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Letter to Martin Van Buren President of the United States 1836". www.cherokee.org/. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016. - ^ "Tribes - Native Voices - 1924: American Indians granted U.S. citizenship". United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on June 29, 2024. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Davis, Ethan. "An Administrative Trail of Tears: Indian Removal". American Journal of Legal History 50, no. 1 (2008): 65–68. Accessed December 15, 2014. Davis, Ethan (2008). "An Administrative Trail of Tears: Indian Removal". The American Journal of Legal History. 50 (1): 49–100. doi:10.1093/ajlh/50.1.49. JSTOR 25664483.

- ^ Harkins, George (1831). "1831 - December - George W. Harkins to the American People". Archived from the original on May 27, 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ Sandra Faiman-Silva (1997). Choctaws at the Crossroads. University of Nebraska Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0803269026.

- ^ de Tocqueville, Alexis (1835–1840). "Tocqueville and Beaumont on Race". Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Satz 1986, p. 7.

- ^ a b Baird, David (1973). "The Choctaws Meet the Americans, 1783 to 1843". The Choctaw People. United States: Indian Tribal Series. p. 36. ASIN B000CIIGTW.

- ^ a b Walter, Williams (1979). "Three Efforts at Development among the Choctaws of Mississippi". Southeastern Indians: Since the Removal Era. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Missall. pp. 83-85.

- ^ Missall. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Sources

- Covington, James W. (1993). The Seminoles of Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-8130-1196-5.

- Morris, Theodore (2004). Florida's Lost Tribes. University Press of Florida. p. 63.

- Prucha 1984, pp. 232–233