Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

quintero21amado

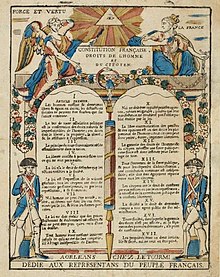

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1789), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can also be translated in the modern era as "Declaration of Human and Civic Rights". Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a significant impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.[1]

The Declaration was initially drafted by Marquis de Lafayette, with assistance from Thomas Jefferson, but the majority of the final draft came from Abbé Sieyès.[2] Influenced by the doctrine of natural right, human rights are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included at the beginning of the constitutions of both the French Fourth Republic (1946) and French Fifth Republic (1958), and is considered valid as constitutional law.

History

[edit]The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment.[3] Lafayette prepared the principal drafts in consultation with his close friend Thomas Jefferson.[4][5] In August 1789, Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[2][6]

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives based on a 24-article draft proposed by the sixth bureau[clarify],[7][8] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.[9]

Background

[edit]

The concepts in the Declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of the Enlightenment, such as individualism, the social contract as theorized by the Genevan philosopher Rousseau, and the separation of powers espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights, as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence, which preceded it (4 July 1776).

These principles were shared widely throughout European society, rather than being confined to a small elite as in the past. This took different forms, such as 'English coffeehouse culture', and extended to areas colonised by Europeans, particularly British North America. Contacts between diverse groups in Edinburgh, Geneva, Boston, Amsterdam, Paris, London, or Vienna were much greater than often appreciated.[10]

Transnational elites who shared ideas and styles were not new; what changed was their extent and the numbers involved.[11] Under Louis XIV, Versailles was the centre of French culture, fashion and political power. Improvements in education and literacy over the course of the 18th century meant larger audiences for newspapers and journals, with Masonic lodges, coffee houses and reading clubs providing areas where people could debate and discuss ideas. The emergence of this "public sphere" led to Paris replacing Versailles as the cultural and intellectual centre, leaving the Court isolated and less able to influence opinion.[12]

Assisted by Thomas Jefferson, then American diplomat to France, Lafayette prepared a draft which echoed some of the provisions of the US declaration. However, there was no consensus on the role of the Crown, and until this question was settled, it was impossible to create political institutions. When presented to the legislative committee on 11 July, it was rejected by pragmatists such as Jean Joseph Mounier, President of the Assembly, who feared creating expectations that could not be satisfied.[13]

Conservatives like Gérard de Lally-Tollendal wanted a bicameral system, with an upper house appointed by the king, who would have the right of veto. On 10 September, the majority led by Sieyès and Talleyrand rejected this in favour of a single assembly, while Louis XVI retained only a "suspensive veto"; this meant he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it. With these questions settled, a new committee was convened to agree on a constitution; the most controversial remaining issue was citizenship, itself linked to the debate on the balance between individual rights and obligations. Ultimately, the 1791 Constitution distinguished between 'active citizens' who held political rights, defined as French males over the age of 25, who paid direct taxes equal to three days' labour, and 'passive citizens', who were restricted to 'civil rights'. As a result, it was never fully accepted by radicals in the Jacobin club.[14]

After editing by Mirabeau, it was published on 26 August as a statement of principle.[6] The final draft contained provisions then considered radical in any European society, let alone France in 1789.[15] French historian Georges Lefebvre argues that combined with the elimination of privilege and feudalism, it "highlighted equality in a way the (American Declaration of Independence) did not".[16] More importantly, the two differed in intent; Jefferson saw the US Constitution and Bill of Rights as fixing the political system at a specific point in time, claiming they 'contained no original thought...but expressed the American mind' at that stage.[17] The 1791 French Constitution was viewed as a starting point, the Declaration providing an aspirational vision, a key difference between the two Revolutions. Attached as a preamble to the French Constitution of 1791, and that of the 1870 to 1940 French Third Republic, it was incorporated into the current Constitution of France in 1958.[2]

Summary of principles

[edit]The Declaration defined a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good."[18] They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.[19]

When it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.[20]

Substance

[edit]The Declaration is introduced by a preamble describing the fundamental characteristics of the rights, which are qualified as "natural, unalienable and sacred" and "simple and incontestable principles" on which citizens could base their demands. In the second article, "the natural and imprescriptible rights of man" are defined as "liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression". It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end to feudalism and to exemptions from taxation, freedom, and equal rights for all "Men" and access to public office based on talent. The monarchy was restricted, and all citizens had the right to participate in the legislative process. Freedom of speech and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests outlawed.[21]

The Declaration also asserted the principles of popular sovereignty, in contrast to the divine right of kings that characterized the French monarchy, and social equality among citizens, "All the citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents," eliminating the special rights of the nobility and clergy.[22]

Articles

[edit]Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III – The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disquieted for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Active and passive citizenship

[edit]

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens. Active citizenship was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants.[24] This meant that at the time of the Declaration, only male property owners held these rights.[25] The deputies in the National Assembly believed that only those who held tangible interests in the nation could make informed political decisions.[26] This distinction directly affects articles 6, 12, 14, and 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, as each of these rights is related to the right to vote and to participate actively in the government. With the decree of 29 October 1789, the term active citizen became embedded in French politics.[27]

The concept of passive citizens was created to encompass those populations excluded from political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Because of the requirements set down for active citizens, the vote was granted to approximately 4.3 million Frenchmen[27] out of a population of around 29 million.[citation needed] These omitted groups included women, the poor, enslaved people, children, and foreigners. As the General Assembly voted upon these measures, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the new French Republic (1792–1804).[26] This legislation, passed in 1789, was amended by the creators of the Constitution of the Year III to eliminate the label of an active citizen.[28] The power to vote was then, however, to be granted solely to substantial property owners.[28]

Tensions arose between active and passive citizens throughout the Revolution. This happened when passive citizens started to call for more rights or openly refused to listen to the ideals set forth by active citizens. Women in particular were strong passive citizens who played a significant role in the Revolution. Olympe de Gouges penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality.[29] By supporting the ideals of the French Revolution and wishing to expand them to women, she represented herself as a revolutionary citizen. Madame Roland also established herself as an influential figure throughout the Revolution. She saw women of the French Revolution as holding three roles; "inciting revolutionary action, formulating policy, and informing others of revolutionary events."[30] By working with men, as opposed to working apart from men, she may have been able to further the fight for revolutionary women. As players in the French Revolution, women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political power.[31]

Women's rights

[edit]The Declaration recognized many rights as belonging to citizens (who could only be male). This was despite the fact that after The March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, women presented the Women's Petition to the National Assembly in which they proposed a decree giving women equal rights.[32] In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d'Aelders unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.[33] Condorcet declared that "he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth abjured his own".[34] The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women's rights and this prompted Olympe de Gouges to publish the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in September 1791.[35]

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen is modeled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and is ironic in the formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality. It states: "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights, they have lost in society."

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point. Camille Naish has described it as "almost a parody... of the original document". The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility." The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied: "Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility". De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law, women were fully punishable yet denied equal rights, declaring, "Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum".[36]

Slavery

[edit]The declaration did not revoke the institution of slavery, as lobbied for by Jacques-Pierre Brissot's Les Amis des Noirs and against by the group of colonial planters called the Club Massiac, because they met at the Hôtel Massiac.[37] Despite the lack of explicit mention of slavery in the Declaration, slave uprisings in Saint-Domingue in the Haitian Revolution were inspired by it, as discussed in C. L. R. James's history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins.[38] In Louisiana, the organizers of the Pointe Coupée Slave Conspiracy of 1795 also drew information from the declaration.[39]

Deplorable conditions for the thousands of enslaved people in Saint-Domingue, the most profitable slave colony in the world, led to the uprisings known as the first successful slave revolt in the New World. Free persons of color were part of the first wave of revolt, but later formerly enslaved people took control. In 1794, the convention was dominated by the Jacobins and abolished slavery, including in the colonies of Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe. However, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802 and attempted to regain control of Saint-Domingue by sending in thousands of troops. After suffering the losses of two-thirds of the men, many to yellow fever, the French withdrew from Saint-Domingue in 1803. Napoleon gave up on North America and agreed to the Louisiana Purchase by the United States. In 1804, the leaders of Saint-Domingue declared it an independent state, the Republic of Haiti, the second republic of the New World. Napoleon abolished the slave trade in 1815.[40] Slavery in France was finally abolished in 1848.

Homosexuality

[edit]The vast amount of personal freedom given to citizens by the document created a situation where homosexuality was decriminalized by the French Penal Code of 1791, which covered felonies; the law simply failed to mention sodomy as a crime, and thus no one could be prosecuted for it.[41] The 1791 Code of Municipal Police did provide misdemeanor penalties for "gross public indecency," which the police could use to punish anyone having sex in public places or otherwise violating social norms. This approach to punishing homosexual conduct was reiterated in the French Penal Code of 1810.

See also

[edit]- Bill of rights

- Human rights in France

- Natural person in French law

- Rights of Man (1791) by Thomas Paine

- Universality

Other early declarations of rights

[edit]- The decreta of León[42][43] (Kingdom of León (Modern Spain) 1188)

- Magna Carta (England, 1215)

- Kouroukan Fouga (Mali Empire, c. 1236)

- Statute of Kalisz (Poland, 1264)

- Henrician Articles and Pacta conventa (Poland, 1573)

- Petition of Right (England, 1628)

- Bill of Rights (England, 1689)

- Claim of Right (Scotland, 1689)

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Bill of Rights (United States, 1789)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of Franchimont (modern-day Belgium, 16 September 1789)

- "Belgian" Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (exiled Belgian and Liégeois revolutionaries in Paris, 23 April 1792)

- Proclamation of Połaniec – Polish historical document (Poland, 7 May 1794)

- "Batavian" Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (Batavian Republic, The Hague, 31 January 1795)

Citations

[edit]- ^ Kopstein Kopstein (2000). Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0521633567.

- ^ a b c Fremont-Barnes 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Lefebvre, Georges (2005). The Coming of the French Revolution. Princeton UP. p. 212. ISBN 0691121885.

- ^ George Athan Billias, ed. (2009). American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776–1989: A Global Perspective. NYU Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0814791394.

- ^ Susan Dunn, Sister Revolutions: French Lightning, American Light (1999) pp. 143–145

- ^ a b Baker 1995, pp. 154–196.

- ^ The original draft is an annex to the 12 August report (Archives parlementaires, 1,e série, tome VIII, débats du 12 août 1789, p. 431).

- ^ Archives parlementaires, 1e série, tome VIII, débats du 19 août 1789, p. 459.

- ^ Fremont-Barnes 2007, p. 159.

- ^ Jourdan 2007, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Jourdan 2007, p. 187.

- ^ Blanning 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Schama 1989, pp. 442–444.

- ^ Ludwikowski 1990, pp. 456–457.

- ^ Ludwikowski 1990, pp. 452–453.

- ^ Lefebvre 1962, p. 146.

- ^ Jefferson 1903, p. May 8, 1825.

- ^ First Article, Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- ^ Merryman, John Henry; Rogelierdomo (2007). The civil law tradition: an introduction to the legal system of Europe and Latin America. Stanford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0804755696.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0812218541.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2008). Western Civilization: 1300 to 1815. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-495-50289-0.

- ^ von Guttner, Darius (2015). The French Revolution. Nelson Cengage. pp. 85–88.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Active Citizen/Passive Citizen · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION". revolution.chnm.org. 1791. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "Thouret 'Report on the Basis of Political Eligibility' (29 September 1789) · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION". revolution.chnm.org. 29 September 1789. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Censer & Hunt 2001, p. 55.

- ^ a b Popkin 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 124.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 420.

- ^ De Gouges, "Declaration of the Rights of Women", 1791.

- ^ Dalton 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Levy & Applewhite 2002, pp. 319–320, 324.

- ^ "Women's Petition to the National Assembly". Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat; Susan Sniader Lanser; David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-55111-255-8.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ The club of reactionary colonial proprietors meeting since July 1789 were opposed to representation in the Assemblée of France's overseas dominions, for fear "that this would expose delicate colonial issues to the hazards of debate in the Assembly", as Robin Blackburn expressed it (Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 [1988:174f]); see also the speech of Jean-Baptiste Belley

- ^ Cf. Heinrich August Winkler (2012), Geschichte des Westens. Von den Anfängen in der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, Third Edition, Munich (Germany), p. 386

- ^ Rasmussen, Daniel (2011). American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt. Harper Collins. p. 89.

- ^ "Napoleon's Decree Abolishing the Slave Trade 29 March 1815". The Napoleon Series. September 2000. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Merrick, Jeffrey; Ragan, Brant T. Jr. (1996). Homosexuality in Modern France. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 82 ff. ISBN 0195357671. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "The Decreta of León of 1188 – The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system". www.unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Versión española de los Decreta de León de 1188" (PDF). www.mecd.gob.es. Spanish Mimisterio de Educació, Cultura y Deporte. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Baker, Keith (1995). "The Idea of a Declaration of Rights". In Van Kley, Dale (ed.). The French Idea of Freedom: The Old Regime and the Declaration of Rights of 1789. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2355-8.

- Blanning, Timothy C. W (1997). The French Revolution: Class War or Culture Clash?. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-67064-4.

- Censer, Jack; Hunt, Lynn (2001). Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Dalton, S. (2001). "Gender and the Shifting Ground of Revolutionary Politics: The Case of Madame Roland". Canadian Journal of History. 36 (2): 259–282. doi:10.3138/cjh.36.2.259. PMID 18711850.

- Doyle, William (1989). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04951-4.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1903). Ford, Paul (ed.). The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. XII: Correspondence and Papers 1808–1816 (2010 ed.). Cosimo Classics. ISBN 978-1-61640-215-0.

- Jourdan, Annie (2007). "The 'Alien Origins' of the French Revolution: American, Scottish, Genevan, and Dutch Influences". The Western Society for French History. 35 (2). University of Amsterdam. hdl:2027/spo.0642292.0035.012.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1962). The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-08598-4.

- Levy, Darline; Applewhite, Harriet (2002). "A Political Revolution for Women? The Case of Paris". The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations (5th ed.). Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. Co. pp. 317–346.

- Ludwikowski, Rhett (1990). "The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and the American Constitutional Development". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 2: 445–462. doi:10.2307/840552. JSTOR 840552. S2CID 143656851.

- Popkin, Jeremy (2006). A History of Modern France. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

- "Active Citizen/Passive Citizen". Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. Project History. 1791. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (2004 ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101727-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Gérard Conac, Marc Debene, Gérard Teboul, eds, La Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789; histoire, analyse et commentaires (in French), Economica, Paris, 1993, ISBN 978-2-7178-2483-4.

- McLean, Iain. "Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen" in The Future of Liberal Democracy: Thomas Jefferson and the Contemporary World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

External links

[edit]- "Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen de 1789". Conseil constitutionnel (in French). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Declaration of human and civic rights of 26 August 1789" (PDF). Conseil constitutionnel. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- 1780s in Paris

- 1789 documents

- 1789 events of the French Revolution

- 1789 in law

- Age of Enlightenment

- Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

- Government of France

- History of human rights

- Human rights in France

- Human rights instruments

- Memory of the World Register

- Political charters

- Popular sovereignty

- Works by Thomas Jefferson