Jeffrey Katzenberg

Jeffrey Katzenberg | |

|---|---|

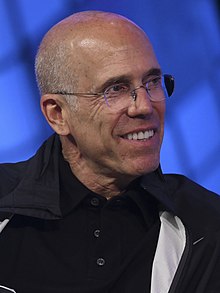

Katzenberg in 2022 | |

| Born | December 21, 1950 New York City, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Organization | WndrCo |

| Notable work | Who Framed Roger Rabbit The Little Mermaid Beauty and the Beast Aladdin The Lion King American Beauty The Prince of Egypt Shrek Kung Fu Panda How to Train Your Dragon |

| Title |

|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Marilyn Siegel (m. 1975) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

Jeffrey Katzenberg (/ˈkætsənˌbɜːrɡ/; born December 21, 1950) is an American media proprietor and film producer who served as chairman of Walt Disney Studios from 1984 to 1994, a position in which he oversaw production and business operations for the company's feature films. Following his departure, he co-founded DreamWorks SKG in 1994,[a] where he served as the company's chief executive officer (CEO) and executive producer of its animated franchises—including Shrek, Madagascar, Kung Fu Panda, and How to Train Your Dragon—until stepping down from the title in 2016. He has since founded the venture capital firm WndrCo in 2017,[1] which invests in digital media projects, and launched Quibi in 2020, a defunct short-form mobile video platform that lost US$1.35 billion in seven months.

Katzenberg has also been involved in politics as an election donor. With active support of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, he was named "one of Hollywood's premier political kingmakers and one of the Democratic Party's top national fund-raisers".[2] He served as a campaign co-chair for Joe Biden's 2024 presidential re-election campaign, and subsequently Kamala Harris' 2024 presidential campaign.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Katzenberg was born on December 21, 1950, in New York City, to a Jewish family, the son of Anne, an artist, and Walter Katzenberg, a stockbroker.[4] He attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, graduating in 1969. When he was 14, Katzenberg volunteered to work on John Lindsay's successful New York mayoral campaign. He quickly received the nickname "Squirt" and attended as many meetings as he could.[5] He went on to attend New York University for one year, before dropping out to work full-time as an advance man for Lindsay.[6][7]

Professional career

[edit]Paramount Pictures

[edit]Katzenberg began his career as an assistant to producer David V. Picker, then in 1974 he became an assistant to Barry Diller, the chairman of Paramount Pictures.[4] Diller moved Katzenberg to the marketing department, followed by other assignments within the studio, until he was assigned to revive the Star Trek franchise, which resulted in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He continued to work his way up and became president of production under Paramount's president, Michael Eisner, overseeing the production of films including 48 Hrs., Terms of Endearment, and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.[8]

The Walt Disney Studios

[edit]In 1984, Eisner became chief executive officer (CEO) of The Walt Disney Company. Eisner brought Katzenberg with him to serve as chairman of The Walt Disney Studios.[4] As head of the studio, he oversaw all filmed content including motion pictures, television, Disney Channel, and home video distribution.[4] Katzenberg was responsible for reviving the studio which, at the time, ranked last at the box office among the major studios. He focused the studio on the production of adult-oriented comedies through its Touchstone Pictures banner, including films such as Down and Out in Beverly Hills, Three Men and a Baby, Good Morning, Vietnam, Dead Poets Society, and Pretty Woman. By 1987, Disney had become the number-one studio at the box office.[9] Katzenberg expanded Disney's film portfolio by launching Hollywood Pictures with Eisner and overseeing the acquisition of Miramax Films in 1993.[5] Katzenberg also oversaw Touchstone Television, which produced television series such as The Golden Girls, Empty Nest and Home Improvement.

Katzenberg was also charged with turning around Disney's ailing Feature Animation unit, creating some intrastudio controversy when he personally edited a few minutes out of a completed Disney animated feature, The Black Cauldron (1985), shortly after joining the company.[10] Under his management, the animation department eventually began creating some of Disney's most critically acclaimed and highest grossing animated features. These films include The Great Mouse Detective (1986), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Oliver & Company (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991)—which was the first animated feature to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture—Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), and Pocahontas (1995).[11][12][unreliable source?] Katzenberg also brokered a deal with Pixar to produce 3D computer-generated animated movies and greenlit production of Toy Story.[13]

Concerns arose internally at Disney, particularly from Eisner and Roy E. Disney, about Katzenberg taking too much credit for the success of Disney's animated releases.[9][14]: 166–168 In 1993, Katzenberg discussed with Eisner the possibility of being promoted to president of the company, which would mean moving Frank Wells from president to vice chairman. Eisner responded that Wells would feel "hurt" in that scenario and then, according to Katzenberg, assured him that he would get the job if Wells vacated the position. After Wells died in a helicopter crash in 1994, Eisner assumed his duties instead of promoting Katzenberg.[15] In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Eisner said that Roy Disney, Walt Disney's nephew and an influential member of the Disney board, did not like Katzenberg and threatened to start a proxy fight if Katzenberg was promoted to president.[16] Tensions between Katzenberg, Eisner and Disney resulted in Katzenberg leaving Disney upon conclusion of his work contract with the company in October 1994.[17][14]: 183, 185 Disney board member Stanley Gold said Katzenberg had been brought low by "his ego and almost pathological need to be important".[15] Katzenberg sued Disney for money he asserted he was owed, and settled out of court for an estimated $250 million in 1999.[8]

DreamWorks SKG

[edit]

Later in 1994, Katzenberg co-founded DreamWorks SKG with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen, with Katzenberg taking primary responsibility for animation operations. He was also credited as producer or executive producer on the DreamWorks animated films The Prince of Egypt (1998), The Road to El Dorado, Chicken Run and Joseph: King of Dreams (all in 2000), Shrek in 2001, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron in 2002, Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas in 2003 and both Shrek 2 and Shark Tale in 2004.

After DreamWorks Animation suffered a $125 million loss on the traditionally animated Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003),[18] Katzenberg believed that telling traditional stories using traditional animation was a thing of the past, and the studio switched to all computer-generated animation, though some of their films would have some small 2D animated sequences.[19] Since then, most of DreamWorks' animated feature films have been successful financially and critically with several Annie Awards and Academy Awards nominations and wins.

DreamWorks Animation

[edit]In 2004, DreamWorks Animation (DWA) was spun off from DreamWorks as a separate company headed by Katzenberg.[20] DWA held an initial public offering that same year in conjunction with the spinoff which raised more than $812 million.[21]

The live-action DreamWorks movie studio was sold to Viacom in December 2005.[22][23] Then in 2008, DreamWorks entered into a new agreement to begin distributing its live-action films through Universal Studios in 2009.[24]

In 2006, Katzenberg made an appearance on the fifth season of The Apprentice. He awarded the task winners an opportunity to be character voices in Over the Hedge.

Katzenberg has been an industry leader in promoting digital 3D production of film, calling it "the greatest advance in the film industry since the arrival of color in the 1930s." When Katzenberg appeared on The Colbert Report on April 20, 2010, he confirmed that from now on "every single movie" that DreamWorks Animation produced would be in 3D and gave Stephen Colbert a pair of new 3D glasses.[25]

NBCUniversal acquired DWA in 2016 for $3.8 billion. Katzenberg left his position as CEO of DWA and was named chairman of DreamWorks New Media (DWN), consisting of DWA's interests in AwesomenessTV and Nova.[26][27] By January 2017, Katzenberg had stepped down from his position with DWN.[28]

WndrCo

[edit]In January 2017, the LA Times reported that Katzenberg had raised funds for a new media and technology investment firm called WndrCo.[28]

Quibi

[edit]In late 2018, Katzenberg announced his new video streaming platform, Quibi, created in partnership with former eBay CEO Meg Whitman.[29][30] The platform specialized in original, short-form content designed for smartphones. Whitman was hired as the company's CEO and first employee. Katzenberg and Whitman created Quibi as a mobile-based Netflix. Their investors included Disney, NBCUniversal, Sony, Viacom, and AT&T's newly rebranded WarnerMedia.[31]

In late 2020, Quibi shut down after just over six months of operation. Katzenberg said the shutdown was due to a sudden change in how audiences consume media caused by the coronavirus pandemic which did not align with Quibi's market niche as well as a desire to return some funds to investors.[32][33] Of the initial $1.65 billion raised, Katzenberg said he was able to return $600 million to investors.[34] To lift Quibi employees' spirits, The Wall Street Journal reported that Katzenberg told them to listen to "Get Back Up Again" from the movie Trolls during a video call announcing the company's closure.[35]

Political activities

[edit]

Katzenberg has been a prominent supporter of Democratic candidates for elected office since the Clinton administration and was an early supporter of Barack Obama. Reportedly "smitten" by Obama's speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, Katzenberg pledged his full support to Obama in 2006 if he decided to run for president. During his campaign, Obama praised Katzenberg for his "tenacious support and advocacy since we started back in 2007."[36][37]

Katzenberg was an avid fundraiser for Obama, doing so while much of Hollywood was still supporting the Clintons. The Wall Street Journal reported his efforts allowed Katzenberg to become an "informal liaison" between Hollywood and the Obama administration.[36] Katzenberg was reportedly Obama's top "bundler", and, with Andy Spahn, had collected at least $6.6 million in combined donations for both of Obama's presidential campaigns.[38] In 2012, Katzenberg organized a fundraiser for Obama's 2012 presidential campaign at the residence of George Clooney. The event reportedly set a record for presidential fundraisers, garnering approximately $15 million.[39] Some Obama campaign officials were unhappy with some of Katzenberg's requests, including that Obama stay and talk with guests at each of the 14 tables at the dinner.[36]

In 2012, the Securities and Exchange Commission reportedly opened an investigation into DreamWorks and other movie studios for bribing foreign officials. It was opened after the announcements of a deal between China and the United States to increase the number of American movies released in China and the launch of Oriental DreamWorks, a Chinese offshoot of DreamWorks Animation.[40] News of the investigation broke shortly after Katzenberg assisted Joe Biden with brokering the Chinese movie deal and Katzenberg had held a fundraiser for the Obama campaign. The timing of the events led Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin to question if the deal and fundraiser were related.[41][40] Katzenberg denied the existence of the investigation, saying that DreamWorks had never been asked for documents or to otherwise cooperate with an investigation.[42]

In October 2012, Obama and Bill Clinton reportedly visited Katzenberg at his home in Beverly Hills for a private meeting with wealthy Democratic donors. The Obama campaign said the meeting was to thank supporters, but some members of the campaign finance committee said that it involved the pro-Obama political action committee Priorities USA Action. Members of the White House press corps who had traveled to California with Obama were kept in the garage of Katzenberg's mansion and one reporter called the meeting "unusual".[43] Katzenberg, who had previously donated $2 million to Priorities USA Action, donated an additional $1 million to the PAC that month.[43][44] Kaztzenberg donated $1 million to Priorities USA Action in 2015, which supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential race.[45] In October 2016, he hosted a $100,000-per-person fundraiser at his Beverly Hills residence with Obama as the main attraction.[46]

In 2018, following the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, Katzenberg pledged $500,000 to the March for Our Lives gun-control demonstration.[47]

Katzenberg donated approximately $1.8 million to a PAC supporting Karen Bass's Los Angeles mayoral bid in 2022.[48]

In 2023, Katzenberg was named as one of the national co-chairs of Joe Biden's 2024 campaign for reelection as president.[49] Katzenberg noted he would provide significant financial support for Biden's re-election.[50] In December 2023, Katzenberg hosted a fundraiser and, at the time, dismissed concerns about Biden's age, instead referring to it as "his superpower".[51]

In 2024, Katzenberg was an advisor to and co-chair of the Biden reelection campaign.[52] After Biden dropped out of the race, Katzenberg became co-chair of Kamala Harris's 2024 presidential campaign.[53]

SOPA/PIPA

[edit]When the White House announced its opposition to the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) in January 2012, Chris Dodd, the former Senator and head of the Motion Picture Association of America, the film industry's lobbying organization, contacted Katzenberg to obtain more information about the president's plans.[54] When Dodd reportedly asked him to intervene, Katzenberg declined,[55] but "sought to soothe hurt feelings and lay the groundwork for a deal more friendly to Hollywood". Katzenberg's office contacted Obama and urged him to contact other studio chiefs in order to reaffirm their support. Obama would take the advice, making Katzenberg one of the few Hollywood executives working on brokering a compromise with Silicon Valley.[36]

Recognition

[edit]Katzenberg was awarded an honorary Doctor of Arts degree by Ringling College of Art and Design in 2008, the first in the school's history.[56]

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Katzenberg with the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2012, in acknowledgment of his role in "raising money for education, art and health-related causes, particularly those benefiting the motion picture industry".[57][58] The following year, Katzenberg was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Obama.[59]

At the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, Katzenberg was awarded an honorary Palme d'Or, the festival's highest prize. Cannes director Thierry Frémaux credited Katzenberg and Shrek with expanding the range of films considered at the competition. Katzenberg compared the distinction to the earlier Academy recognition.[60]

Personal life

[edit]

Katzenberg married Marilyn Siegel, a kindergarten teacher, in 1975. They have twin children, Laura and David, born in 1983.[61] David is a television producer and director.[62][63]

Katzenberg and his wife have been highly active in charitable causes. They donated the multimillion-dollar Katzenberg Center to Boston University's College of General Studies, citing that the school gave their two children the "love of education".[64] They also donated the Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Center for Animation at the University of Southern California.

Katzenberg sits on the board of directors of multiple organizations, including the Motion Picture & Television Fund, Geffen Playhouse, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, AIDS Project Los Angeles, The Michael J. Fox Foundation, California Institute of the Arts, Simon Wiesenthal Center, and the USC School of Cinematic Arts. In 2008, Katzenberg founded the DreamWorks Animation Academy in partnership with Inner-City Arts, a Los Angeles-based art education nonprofit organization, to provide inner-city students with instruction in digital media production.[65][66]

Katzenberg had an estimated worth of $900 million in 2016.[67]

Filmography

[edit]Films

[edit]Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Occupation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Father of the Pride | Creator/Executive producer | 2 episodes |

| 2005–2009 | The Contender | Executive producer | 26 episodes |

| 2005 | The Contender Rematch: Mora vs. Manfredo | TV special | |

| 2008 | The Contender Asia | 12 episodes | |

| 2010 | Neighbors from Hell | 5 episodes | |

| 2020 | Dummy | Producer | wiip, Heller Highwater Pictures, Let's Go Again |

| Thanks a Million | Short TV series | ||

| Elba vs. Block | |||

| Beauty | Short series | ||

| Benedict Men | TV series | ||

| 2022 | The Now | Executive producer | |

| 2021 | Natural Born Narco |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Katzenberg represents the K in DreamWorks SKG.

References

[edit]- ^ Garfinkle, Alexandra (June 23, 2023). "Jeffrey Katzenberg's unexpected take on AI – here's what he and Netomi CEO had to say". Finance.Yahoo.com.

- ^ Daunt, Tina; Masters, Kim (October 30, 2013). "Jeffrey Katzenberg's Secret Call to Hillary Clinton: Hollywood's 2016 Support Assured". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ "Joe Biden is redefining presidential campaign frugality". POLITICO. July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Harmetz, Aljean (February 7, 1988). "Who Makes Disney Run?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Pulver, Andrew (May 17, 2001). "The Katz that bit the mouse". The Guardian.

- ^ "Jeffrey Katzenberg". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ Kahn, Carrie (May 11, 2012). "Head Of Shrek's Studio Puts Millions Behind Obama". NPR. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Pulver, Andrew (May 17, 2001). "The Katz that bit the mouse". The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Hahn, Don (2009). Waking Sleeping Beauty (Documentary film). Burbank, California: Stone Circle Pictures/Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (1991). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York.: Hyperion. p. 114. ISBN 1-56282-899-1.

- ^ The Disney Renaissance Didn't Happen Because of Jeffrey Katzenberg; It Happened In Spite of Him

- ^ Four Wins of the Disney Renaissance that Happened in Spite of Jeffrey Katzneberg

- ^ Borden, Mark (December 1, 2009). "Jeffrey Katzenberg Plans on Living Happily Ever After". Fast Company. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Stewart, James B. (2006). DisneyWar. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6709-0. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Masters, Kim (April 9, 2014). "The Epic Disney Blow-Up of 1994: Eisner, Katzenberg and Ovitz 20 Years Later". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Michael Eisner on Former Disney Colleagues, Rivals and Bob Iger's Successor". The Hollywood Reporter. July 27, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (August 25, 1994). "Chairman of Disney Studios Resigns". The New York Times.

- ^ Eller, Claudia; Hofmeister, Sallie (December 17, 2005). "DreamWorks Sale Sounds Wake-Up Call for Indie Films". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

The company nearly went bankrupt twice, Geffen said during a panel discussion in New York this year, adding that when the animated film "Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas" flopped in 2003, the resulting $125-million loss nearly sank his company.

- ^ M. Holson, Laura (July 21, 2003). "Animated Film Is Latest Title To Run Aground At DreamWorks". The New York Times. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

'I think the idea of a traditional story being told using traditional animation is likely a thing of the past', he said. Among other factors, Mr. Katzenberg said, 'fast-evolving technology is making it easier to create images that a few years ago could only be drawn by hand.'

- ^ Spangler, Todd (January 26, 2017). "Jeffrey Katzenberg's Investment Venture WndrCo Raises $591.5 Million". Variety. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Crawford, Krysten (October 29, 2004). "The animation flood: Too much Shrek? Hollywood can't get enough of computer animation flicks. Will moviegoers join the binge?". CNN. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "'Island' Could Sink DreamWorks Sale – Celebrity Gossip | Entertainment News". FOXNews.com. August 1, 2005. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Sean (December 19, 2005). "Hollywood: DreamWorks Sale—Why the Dream Didn't Work – Newsweek – Newsweek Periscope". MSNBC. Archived from the original on December 13, 2005. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Keating, Gina (October 13, 2008). "Universal Studios to distribute DreamWorks films". Reuters. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Colbert Nation". Colbert Report – Jeffrey Katzenberg. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ Laporte, Nicole (April 28, 2016). "How Jeffrey Katzenberg Created, Built, And Sold DreamWorks Animation". Fast Company. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ James, Meg (April 28, 2016). "Comcast's NBCUniversal buys DreamWorks Animation in $3.8-billion deal". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Faughnder, Ryan (January 26, 2017). "Former DreamWorks Chief Jeffrey Katzenberg raises nearly $600 million for his next act". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Schwartzel, Erich (December 20, 2018). "Meg Whitman Wants to Change What You Watch". Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (June 14, 2019). "What Is Jeffrey Katzenberg's Quibi All About, and Why Should You Care?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ "Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman Reveal the Name of Their 'NewTV' Platform". Fortune.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (May 11, 2020). "Jeffrey Katzenberg Blames Pandemic for Quibi's Rough Start". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (October 21, 2020). "Quibi's Jeffrey Katzenberg & Meg Whitman Detail "Clear-Eyed" Decision To Shut It Down". Deadline. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Jeffrey Katzenberg on How Quibi Experience Informs His VC Ambitions". Bloomberg.com. June 23, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Farrell, Maureen; Flint, Joe; Mullin, Benjamin (October 22, 2020). "Quibi Is Shutting Down Barely Six Months After Going Live". WSJ. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Nicholas, Peter; Orden, Erica (September 30, 2012). "Movie Mogul's Starring Role in Raising Funds for Obama". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 23, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (May 11, 2012). "The Katzenberg-Obama connection". Politico. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Confessore, Nicholas (September 12, 2012). "Obama Grows More Reliant on Big-Money Contributors". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Kahn, Carrie (May 11, 2012). "Head Of Shrek's Studio Puts Millions Behind Obama". NPR. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Wyatt, Edward; Cieply, Michael; Barnes, Brooks (April 24, 2012). "S.E.C. Asks if Hollywood Paid Bribes in China". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Rubin, Jennifer (June 1, 2012). "Biden's role in U.S. companies' deals with China". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Berrin, Danielle (July 17, 2013). "Jeffrey Katzenberg: Mogul on a mission". Jewish Journal. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Daunt, Tina (October 7, 2012). "Obama, Clinton Powwow with Donors at Jeffrey Katzenberg's House". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg Give $1 Million Each to Aid Obama Super PAC". Huffington Post. October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Faughnder, Ryan (April 28, 2016). "Katzenberg to relinquish DreamWorks Animation CEO role after Comcast deal". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Gardner, Chris (October 24, 2016). "Inside Jeffrey Katzenberg's Final Fundraiser for President Obama". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Oprah Follows George and Amal Clooney's Lead, to Donate $500,000 for Parkland Students' March". February 20, 2018. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ Oreskes, Benjamin (October 6, 2022). "Jeffrey Katzenberg donates $1 million to support Karen Bass' bid for L.A. mayor". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Ken; Lucey, Catherine (June 26, 2023). "Jeffrey Katzenberg's Very Hollywood Advice for Joe Biden". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Culture, Sophie Lloyd Pop; Reporter, Entertainment (April 5, 2024). "Full list of celebrities supporting Joe Biden over Donald Trump". Newsweek. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (July 14, 2023). "Jeffrey Katzenberg Calls Joe Biden's $72 Million Fundraising Total A "Blockbuster" Number, Says POTUS's Age Is His "Superpower"". Deadline. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Baker, Peter (June 13, 2024). "A Hollywood Heavyweight Is Biden's Secret Weapon Against Trump". The New York Times.

- ^ Saric, Ivana (August 1, 2024). "Harris campaign hands Democrats a Hollywood glow up". Axios. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ Welch, Chris (January 26, 2012). "Inside Hollywood's failed SOPA efforts — and a glimmer of hope". The Verge. Retrieved October 27, 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Andy. "Meet the New George Soros". Mother Jones. Retrieved October 27, 2024.

- ^ "DreamWorks Animation CEO Jeffery Katzenberg to speak at Ringling College of Art and Design's 2008 Commencement". Tampa Bay CEO Magazine. April 15, 2008. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Groom, Nichola (December 2, 2012). "Producer Katzenberg picks up honorary Oscar for charity work". Reuters. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (September 5, 2012). "Academy to honor Jeffrey Katzenberg, Hal Needham, D.A. Pennebaker and George Stevens Jr". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Fritz, Ben; Schwartzel, Erich; Ballhaus, Rebecca (July 22, 2014). "Obama Mega-Donor Jeffrey Katzenberg to Receive National Arts Medal". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Richford, Rhonda (May 19, 2017). "Cannes: Jeffrey Katzenberg Feted With Honorary Palme d'Or". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Berrin, Danielle (July 17, 2013). "Jeffrey Katzenberg: Mogul on a mission". Jewish Journal. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ Howard, Caroline; Noer, Michael (December 17, 2012). "30 under 30". Forbes. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Radish, Christina (April 14, 2011). "Producer David Katzenberg Talks THE HARD TIMES OF RJ BERGER Season 2". Collider.com. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "BU Today News & Events". CGS dedicates Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Center. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (September 5, 2012). "Academy to honor Jeffrey Katzenberg, Hal Needham, D.A. Pennebaker and George Stevens Jr". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Pener, Degen (August 8, 2012). "Jeffrey and Marilyn Katzenberg to Be Honored at Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network Gala (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Katzenberg Net Worth Climbs to Nearly $900 Million After Comcast Buys DreamWorks Animation". Forbes. August 26, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Jeffrey Katzenberg

- 1950 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- American chief executives

- American chief executives in the media industry

- American film producers

- American film studio executives

- American film production company founders

- American gun control activists

- 20th-century American Jews

- American philanthropists

- Businesspeople from New York City

- California Democrats

- DreamWorks Animation people

- American mass media company founders

- Disney executives

- Ethical Culture Fieldston School alumni

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- Joe Biden 2024 presidential campaign

- Kamala Harris 2024 presidential campaign

- People associated with the 2024 United States presidential election

- New York (state) Democrats

- Paramount Pictures executives

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Walt Disney Animation Studios people

- 21st-century American Jews

- Mass media people from New York City

- People from New York (state)

- Jewish film people