Pacoima, Los Angeles

Pacoima | |

|---|---|

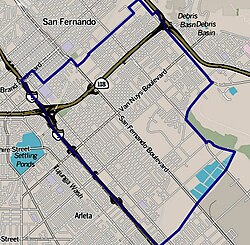

Boundaries of Pacoima as drawn by the Los Angeles Times | |

| Coordinates: 34°15′58″N 118°25′19″W / 34.26611°N 118.42194°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| City | Los Angeles |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 91331, 91333–91334 |

| Area code(s) | 818, 747 |

Pacoima (Tataviam language: Pakoinga, meaning "entrance")[1][2][3] is a neighborhood in Los Angeles, California. It is one of the oldest neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley region of LA.[4]

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]Pacoima is bordered by the Los Angeles districts of Mission Hills on the west, Arleta on the south, Sun Valley on the southeast, Lake View Terrace on the northeast, and by the city of San Fernando on the north.

It covers an area of 7.14 sq mi (18.5 km2).[5]

Landscape

[edit]Ed Meagher of the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1955 that the 110-block area on the north side of San Fernando Road in Pacoima consisted of what he described as a "smear of sagging, leaning shacks and backhouses framed by disintegrating fences and clutter of tin cans, old lumber, stripped automobiles, bottles, rusted water heaters and other bric-a-brac of the back alleys."[6] In 1955 Pacoima lacked curbs, paved sidewalks, and paved streets. Pacoima had what Meagher described as "dusty footpaths and rutted dirt roads that in hard rains become beds for angry streams."[6] Meagher added that the 450 houses in the area, with 2,000 inhabitants, "squatted" "within this clutch of residential blight."[6] He described most of the houses as "substandard." Around 1955, the price of residential property increased in value, as lots that sold years prior for $100 sold for $800 in 1955. Between 1950 and 1955, property values on Van Nuys Boulevard increased six times. In late 1952, the Los Angeles City Council allowed the Building and Safety Department to begin a slum clearance project to try to force homeowners who had houses deemed substandard to repair, demolish, or vacate those houses. In early 1955, the city began a $500,000 project to add 9 mi (14 km) of curbs, sidewalks, and streets. Meagher said that the "neatness and cleanness" [sic] of the new infrastructure were "a challenge to homeowners grown apathetic to thoroughfares ankle deep in mud or dust."[6] Some area businessmen established the San Fernando Valley Commercial & Savings Bank in November 1953 to finance area rehabilitation projects after other banks persistently refused to give loans to those projects.[6]

In late 1966, a city planning report described the central business district of Pacoima along Van Nuys Boulevard as "a rambling, shallow strip pattern of commercial uses... varying from banks to hamburger stands, including an unusual number of small business and service shops."[7] A Los Angeles Times article stated that the physical image of the area was "somewhat depressing." The council recommended the establishment of smaller community shopping centers. The article stated that the Pacoima Chamber of Commerce was expected to oppose the recommendation, and that the chamber favored deepening of the existing commercial zones along Laurel Canyon Boulevard and Van Nuys Boulevard. The council noted the lack of parking spaces and storefronts that appeared in disrepair or vacant. The report recommended establishing shopping centers in areas outside of the Laurel Canyon-Van Nuys commercial axis. The article stated that some sections of Laurel Canyon were "in a poor state of repair" and that there were "conspicuously minimal" curbs and sidewalks. The report recommended continued efforts to improve sidewalks and trees. The report advocated the establishment of a community center to "give Pacoima a degree of unity." Most of the residences in Pacoima were "of an older vintage." The article said most of the houses and yards, especially in the R-2 duplex zones, exhibited "sign[s] of neglect." The report said that the range of types of houses was "unusually narrow for a community of this size." The report also said that the fact had a negative effect on the community that was reflected by a lack of purchasing power. The report added "Substandard home maintenance is widespread and borders on total neglect in some sectors." The report recommended establishing additional apartments in central Pacoima; the Los Angeles Times report said that the recommendation was "clouded" by the presence of "enough apartment-zoned land to last 28 years" in the San Fernando Valley.[7]

In 1994, according to Timothy Williams of the Los Angeles Times, there were few boarded-up storefronts along Pacoima's main commercial strip along Van Nuys Boulevard,[8] and no vacancies existed in Pacoima's main shopping center.[8] Williams added that many of the retail outlets in Pacoima consisted of check-cashing outlets, storefront churches, pawn shops, and automobile repair shops. Williams added that the nearest bank to the commercial strip was "several blocks away." In 1994 almost one third of Pacoima's residents lived in public housing complexes. Williams said that the complexes had relatively little graffiti. Many families who were on waiting lists to enter public housing complexes lived in garages and converted tool sheds, which often lacked electricity, heat, and/or running water. Williams said that they lived "out of sight."[8]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Pacoima, Los Angeles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

75 (24) |

78 (26) |

84 (29) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

88 (31) |

82 (28) |

73 (23) |

67 (19) |

78 (26) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 44 (7) |

45 (7) |

46 (8) |

48 (9) |

52 (11) |

56 (13) |

59 (15) |

61 (16) |

58 (14) |

53 (12) |

46 (8) |

43 (6) |

51 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.01 (102) |

4.50 (114) |

3.74 (95) |

0.96 (24) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.52 (13) |

1.38 (35) |

2.17 (55) |

18.16 (461) |

| Source: [9] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Until 1848

[edit]The area was first inhabited by the Fernandeño-Tongva and Tataviam people, California Indian Tribes, now known as Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.[10][11] The original name for the Native American village in this area was actually Pakoinga or Pakɨynga in Fernandeño, but since the "ng" sound (a voiced velar nasal) did not exist in Spanish, the Spaniards mistook the sound as an "m" and recorded the name as Pacoima, as is seen today.[12]

Pacoima's written history dates to 1769 when Spaniards entered the San Fernando Valley.[13] In 1771, nearby Mission San Fernando Rey was founded, with Native Americans creating gardens for the mission in the area.[14] They lived at the mission working on the gardens which, in a few years, had stretched out over most of the valley.[15]

The Mexican government secularized the mission lands in 1834 by taking them away from the church. The first governor of California, Pio Pico, leased the lands to Andrés Pico, his brother. In 1845, Pio Pico sold the whole San Fernando Valley to Don Eulogio de Celis for $14,000 to raise money for the war between Mexico and the United States, settled by a treaty signed at Campo de Cahuenga in 1845, and by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The Pacoima area became sheep ranches and wheat fields.[15]

Municipality

[edit]In 1873, Senator Charles Maclay of Santa Clara purchased 56,000 acres (230 km2) in the northern part of the San Fernando Valley adjacent to the San Fernando Mission and in 1887, Jouett Allen bought 1,000 acres (400 ha) of land between the Pacoima Wash and the Tujunga Wash. The land he purchased was from the Maclay Rancho Water Company, which had taken over Senator Charles Maclay’s holdings in the Valley. Allen retained 500 acres (200 ha) for himself and subdivided the remainder in 1-acre (4,000 m2) tracts. It was from this that the town of Pacoima was born.[15] The subdivision’s original boundaries were Paxton Street on the north, Herrick Avenue on the east, Pierce Street on the south, & San Fernando Road on the west.[16]

The town was built in keeping with the new Southern Pacific railroad station. Shortly after the rail line had been established, the Southern Pacific Railroad chose the site for a large brick passenger station, which was considered to be one of the finest on their line. Soon large spacious and expensive two-story homes made their appearance, as the early planners had established building restrictions against anything of a lesser nature. The first concrete sidewalks and curbs were laid and were to remain the only ones in the San Fernando Valley for many years.[15]

In 1888, the town's main street, 100 ft (30 m) wide and 8 mi (13 km) long, was laid through the center of the subdivision. The street was first named Taylor Avenue after President Taylor; later it was renamed Pershing Street. Today it is known as Van Nuys Boulevard. Building codes were established, requiring that homes built cost at least USD$2,000. The land deed contained a clause that if liquor was sold on this property, it would revert to Jouett Allen or his heirs.[15]

But like the railroad station, the large hotel, the big two-story school building and many commercial buildings, most were torn down within a few years as the boom days receded. The early pioneers had frowned upon industry, which eventually resulted in the people moving away from the exclusive suburb which they had set up to establish new homes closer to their employment and Pacoima returned to its rural, agricultural roots.[15]

In 1916, the presently named Pacoima Chamber of Commerce was established as the Pacoima Chamber of Farmers. For many years, the fertile soil produced abundant crops of olives, peaches, apricots, oranges and lemons. The opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct brought a new supply of water to the area. With the new water supply, the number of orchards, farms and poultry ranches greatly increased and thoroughbred horses began to be raised.[15]

Los Angeles annexed the land, including Pacoima, as part of ordinance 32192 N.S. on May 22, 1915.[17]

1940s: World War II

[edit]During World War II, the rapid expansion of the workforce at Lockheed's main plant in neighboring Burbank and need for worker housing led to the construction of the San Fernando Gardens housing project.[citation needed] By the 1950s, the rapid suburbanization of the San Fernando Valley arrived in Pacoima, and the area changed almost overnight from a dusty farming area to a bedroom community for the fast-growing industries in Los Angeles and nearby Burbank and Glendale, with transportation to and from Pacoima made easy by the Golden State Freeway.[citation needed]

Beginning in the late 1940s, parts of Pacoima started becoming a place where Southern Californians escaping poverty in rural areas settled. In the post–World War II era, many African Americans settled in Pacoima after arriving in the area during the second wave of the Great Migration since they had been excluded from other neighborhoods due to racially discriminatory covenants.[18] By 1960, almost all of the 10,000 African Americans in the San Fernando Valley lived in Pacoima and Arleta as it became the center of African-American life in the Valley.[8]

1957 airplane crashes

[edit]On January 31, 1957, a Douglas DC-7B operated by Douglas Aircraft Company was involved in a mid-air collision and crashed into the schoolyard of Pacoima Middle School, then named Pacoima Junior High School.[19][20] By February 1, seven people had died, and about 75 had been injured due to the incident.[21] A 12-year-old boy died from multiple injuries from the incident on February 2.[22] On June 10, 1957, a light aircraft hit a house in Pacoima; the four passengers on board died, and eight people in the house sustained injuries.[23]

1960s to present

[edit]In 1966, Los Angeles city planners wrote a 48-page report noting that Pacoima does not have a coherent structure to develop businesses in the central business district, lacks civic pride, and has poor house maintenance.[7]

By the late 1960s, immigrants from rural Mexico began to move to Pacoima due to the low housing costs and the neighborhood's proximity to manufacturing jobs. African Americans who were better established began to move out and, in an example of ethnic succession, within less than two decades, the African American population was replaced by a poorer Latino immigrant population. Immigrants from Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador settled in Pacoima.[8] Seventy-five percent of Pacoima's residents were African Americans in the 1970s. According to the 1990 U.S. Census, 71% of Pacoima's population was of Hispanic/Latino descent while 10% was African American.[8]

The closing of factories in the area around Pacoima in the early 1990s caused residents to lose jobs, reducing the economic base of the neighborhood; many residents left Pacoima as a result.[8] By 1994, Pacoima was the poorest area in the San Fernando Valley. One in three Pacoima residents lived in public housing. The poverty rate hovered between 25% and 40%. In 1994, Williams wrote of Pacoima, "one of the worst off" neighborhoods in Los Angeles "nevertheless hides its poverty well." Williams cited the lack of homeless people on Pacoima's streets, the fact that no vacancies existed in Pacoima's major shopping center, and the presence of "neat" houses and "well-tended" yards. Williams added that in Pacoima "holding a job is no guarantee against being poor." In 1994, Howard Berman, the U.S. Congress representative of an area including Pacoima, and Los Angeles City Council member Richard Alarcon advocated including a 2 sq mi area (5.2 km2) in the City of Los Angeles's bid for a federal empowerment zone. The proposed area, with 13,000 residents in 1994, included central Pacoima and a southern section of Lake View Terrace.[8]

Economy

[edit]In the early 1950s to early 1960s, which was the time of the greatest single-family housing construction and population expansion in Pacoima, most residents worked in construction, factory and other blue-collar fields.[8] By 1994 this had changed and many Pacoima residents were then employed at area factories. From 1990 to 1994, Lockheed cut over 8,000 jobs at its Burbank, California plant. General Motors closed its Van Nuys plant in 1992, causing the loss of 2,600 jobs. Timothy Williams of the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1994, "For years, those relatively high-paying jobs had provided families with a springboard out of the San Fernando Gardens and Van Nuys Pierce Park Apartments public housing complexes." After the jobs were lost, many longtime Pacoima residents left the area.[8] In the 1990 U.S. Census the unemployment rate in Pacoima was almost 14%, while the City of Los Angeles had an overall 8.4% overall unemployment rate. Many Pacoima residents who worked made less than $14,000 annually: the U.S. government's poverty line for a family of four. Most residents owned their houses.[8]

Juicy Couture, an apparel company, was founded here in 1996.[24]

In 1955, Ed Meagher of the Los Angeles Times said the "hard-working" low income families of Pacoima were not "indignents [sic] or transients", but they "belong to the community and have a stake in it." In 1955 P.M. Gomez, the owner of a grocery store in Pacoima, said in a Los Angeles Times article that most of the homeowners in Pacoima were not interested in moving to the San Fernando Gardens complex that was then under development, since most of the residents wanted to remain homeowners.[8] A 1966 city planning report criticized Pacoima for lacking civic pride, and that the community had no "vital community image, with no apparent nucleus or focal point."[7]

In 1994, Timothy Williams of the Los Angeles Times noted how Pacoima was "free of the overt blight found in other low-income neighborhoods is no accident." Cecila Costas, who was the principal of Maclay Middle School during that year, said that Pacoima was "a very poor community, but there's a tremendous amount of pride here. You can be poor, but that doesn't mean you have to grovel or look like you are poor."[8] Williams said that the African-American and Hispanic populations of Pacoima did not always have cordial relations. He added that by 1994 "the mood has shifted from conflict to conciliation as the town has become increasingly Latino."[8]

Demographics

[edit]The majority of the population is Hispanic.[25]

According to Mapping L.A., Mexican and German were the most common ancestries in 2000. Mexico and El Salvador were the most common foreign places of birth.[26]

2008

[edit]In 2008, the city estimated that the population was 81,318 with a density of approximately 10,510 people per square mile.[27]

2010

[edit]The 2010 U.S. census counted 103,689 residents in Pacoima's 91331 ZIP Code. The median age was 29.5, and the median yearly household income at that time was $49,842.[28]

Government and infrastructure

[edit]Local

[edit]The Los Angeles Police Department operates the Foothill Community Police Station in Pacoima.[29] The Los Angeles Fire Department operates Fire Station 98 in Pacoima.[30][31] The Los Angeles County Fire Department operates a department facility in Pacoima that houses, among others the Forestry Division, Air and Heavy Equipment and Transportation operations.[32]

County and federal

[edit]The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services operates the Pacoima Health Center which is located along Van Nuys Boulevard in Pacoima.[33]

The United States Postal Service Pacoima Post Office is located on Van Nuys Boulevard.[34]

Politically, Pacoima is represented by Tony Cárdenas in Congress, Caroline Menjivar in the State Senate, and Luz Rivas in the Assembly.

Transportation

[edit]The major transportation routes across and through the area are San Fernando Road, Van Nuys Boulevard, and Laurel Canyon Boulevard. California State Route 118 (Ronald Reagan) runs through it, and the community is bordered by the I-5 (Golden State).[35]

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA) operates bus services in Pacoima.[36] Metro operates Metro Rapid line 761 along Van Nuys Boulevard from Sylmar/San Fernando Station to the Expo/Sepulveda Station. Metro Local Lines 92, 166, 224, 230, 233, 294 and 690 operate in Pacoima. In 2031, Metro will open the East San Fernando Valley Light Rail Transit Project light rail project with three stations at Laurel Canyon Boulevard and Van Nuys Boulevard, San Fernando Road and Van Nuys Boulevard, and San Fernando Road & Paxton Street. Whiteman Airport, a general aviation airport owned by the County of Los Angeles, is located in Pacoima.

Crime

[edit]Crime increased in Pacoima in the 1970s. Timothy Williams of the Los Angeles Times said that an "unprecedented wave of activism" countered the crime surge. Residents led by social institutions such as churches, schools, and social service agencies held marches and rallies. Schools remained open on weekends and in evenings to offer recreational and tutoring programs. Residents circulated petitions to try to stop the establishment of liquor stores. Residents began holding weekly meetings with a gang that, according to Williams, "had long been a neighborhood scourge." Area police officers said, in Williams's words, "although crime in Pacoima remains a major problem", particularly in the area within the empowerment zone proposed by area politicians in the 1990s, "the situation is far improved from the 1980s."[8]

Officer Minor Jimenez, who was the senior lead police officer in the Pacoima area in 1994 and had been for a 3½ year period leading up to 1994, said that the community involvement was the main reason for the decrease in crime because the residents cooperated with the police and "the bad guys know it." After the activism in the area occurred, major crime was reduced by 6%. Residents reached an agreement with liquor store owners; the owners decided to erase graffiti on their properties within 24 hours of reaching the agreement. The owners also stopped the sale of individual cold containers of beer to discourage public consumption of alcohol. Williams said "The activism appears to have paid off." The resident meetings with Latino gang members resulted in a 143-day consecutive period of no drive by shootings.[8]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The David M. Gonzales Recreation Center, which originally opened as the Pacoima Recreation Center on June 1, 1950, was rededicated on June 1, 1990. The rededication included a plaque to David M. Gonzales, a soldier in World War II who died in the Battle of Luzon. The center has an auditorium, indoor gymnasium and basketball court. In addition, the center has an outdoor gymnasium with weights, lit baseball diamond, basketball and handball courts and a soccer field. It also features picnic tables, a children's play area and a community room. Gonzales Recreation Center is also used as a stop-in facility by the Los Angeles Police Department.[37]

Originally named Paxton Park, Ritchie Valens Park,[38] Recreation Center[39] and pool are located near the north end of Pacoima.[40] Valens Park has an impressive list of amenities, including an indoor auditorium and gymnasium, both a lit and unlit baseball diamond, indoor basketball courts and outdoor lit basketball courts, children's play area, community room, handball courts, kitchen, jogging path, picnic tables, unlit soccer field, a stage, and lit tennis courts.[38] The outdoor pool is seasonal and unheated.[40] In the 1990s Richard Alarcon, a Los Angeles City Council member who represented Pacoima, proposed changing the name of Paxton Park to honor Ritchie Valens. Hugo Martin of the Los Angeles Times said in 1994 that Alarcon proposed the rename so Pacoima residents will "remember Valens's humble background and emulate his accomplishments."[41] The annual Ritchie Valens Fest, a festival, was created in 1994 to honor the renaming of the park.[42]

The Hubert H. Humphrey Memorial Park, public swimming pool, and Recreation Center are located near the northern end of Pacoima. The pool is one of only a few citywide which is a year-round outdoor heated pool.[43] The park has a number of barbecue pits and picnic tables as well as a lit baseball diamond, basketball courts, football field, handball and volleyball courts. Other features include, a children's play area, an indoor gymnasium and a center for teenagers which has a kitchen and a stage.[44]

The Hansen Dam Municipal Golf Course, opened in 1962 as an addition to Hansen Dam Recreation Area, is located on the northwest boundary of Pacoima.[45] Although Hansen Dam Recreation Area is actually located in Lake View Terrace, a short distance beyond the true northwest boundary of Pacoima, they have always been associated with Pacoima.[46] The golf course also features a lit driving range, practice chipping and putting greens. There is club and electric or hand cart rental service, a restaurant and snack bar.[47][48] In 1974 a clubhouse was added.[49]

The Roger Jessup Recreation Center is an unstaffed small park in Pacoima. The park includes barbecue pits, a children's play area, a community room, and picnic tables.[50]

Education

[edit]Data from the United States Census Bureau show the percentage of Pacoima residents aged 25 and older who had obtained a four-year degree or higher is generally lower than the percentage of Los Angeles City and Los Angeles County residents, based on 30-year data spanning from 1991 to 2020.

| Year | Pacoima | Los Angeles City | Los Angeles County |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991-1995 | 6.1% | 20.4% | 22.3% |

| 1996-2000 | 6.6% | 23.3% | 24.3% |

| 2001-2005 | 8.1% | 26.4% | 27.1% |

| 2006-2010 | 10.5% | 29.4% | 29.9% |

| 2011-2015 | 12.5% | 32.1% | 32.6% |

| 2016-2020 | 13.7% | 35.0% | 35.4% |

Schools

[edit]

Schools within the Pacoima boundaries are:[52]

Public

[edit]Los Angeles Unified School District

- San Fernando High School

- Hillery T. Broadus Elementary School, 12651 Filmore Street

- Vaughn Next Century Learning Center, 13330 Vaughn Street

- Discovery Charter Preparatory No. 2, high school, 13570 Eldridge Avenue

- Charles Maclay Middle School, 12540 Pierce Avenue

- Mission Continuation School, 11015 O'Melveny Avenue

- Sara Coughlin Elementary School, 11035 Borden Street

- Pacoima Charter Elementary School, 11016 Norris Avenue

- Telfair Avenue Elementary School, 10975 Telfair Avenue

- Haddon Avenue Elementary School, 10115 Haddon Avenue

- Pacoima Middle School, 9919 Laurel Canyon Boulevard

- Montague Charter Academy, 13000 Montague Street

- Bert Corona Charter School, middle, 9400 Remick Avenue

- iLEAD Pacoima, K-8 (K-12 planned for fall 2016), 11251 Glenoaks Blvd.

Students in Pacoima are zoned to one of three high schools: San Fernando High, Sun Valley High School or John H. Francis Polytechnic High School.[53][54]

Private

[edit]- Guardian Angel Elementary School, 10919 Norris Avenue

- Mary Immaculate Elementary School, 10390 Remick Avenue

- Branford Grove School, 13044 Chase Street

- Soledad Enrichment Action School, 13456 Van Nuys Boulevard

Public libraries

[edit]

Los Angeles Public Library operates the Pacoima Branch Library in Pacoima.[55]

By 1958, the City of Los Angeles started negotiations to purchase a site to use as the location of a library in Pacoima.[56] The city was scheduled to ask for bids for the construction of the library in May 1960.[57] The library, scheduled to open on August 23, 1961,[58] was a part of a larger $6.4 million library expansion program covering the opening of a total of six libraries in the San Fernando Valley and three other libraries.[59] The previous Pacoima Library, with 5,511 sq ft (512.0 m2) of space,[60] had around 50,300 books in 2000.[61] In 1978 Pacoima residents protested after the City of Los Angeles decreased library services in Pacoima in the aftermath of the passing of Proposition 13.[62] The Homework Center opened in the library in 1994.[63]

In 1998 Angelica Hurtado-Garcia, then the branch librarian of the Pacoima Branch, said that the community had outgrown the branch and needed a new one. During that year, a committee of the Los Angeles City Council recommended spending $600,000 in federal grant funds to develop plans to build two library branches in the San Fernando Valley, including one in Pacoima.[64] The groundbreaking for the 10,500 sq ft (980 m2) current Pacoima Branch Library, scheduled to have a collection of 58,000 books and videos, was held in 2000.[61] The new library opened in 2002. Hurtado, who was still the senior librarian in 2006, said that the new library, in the words of Alejandro Guzman of the Los Angeles Daily News, was "more attractive and inviting to the community" than the previous one.[65]

Religion

[edit]- Churches in Pacoima

|

|

Notable people

[edit]- Judy Baca, painter and social activist[66]

- Kenya Barris

- Bobby Chacon, two-time world boxing champion.[67]

- Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter[68]

- Miguel González, pitcher for the Texas Rangers[69]

- Howard Huntsberry, musician and actor

- Alex Padilla, United States Senator[70]

- DaShon Polk, professional football player[71]

- Levi Ponce, artist.[72]

- Danny Trejo, actor[73]

- Ritchie Valens, singer and recording artist[41]

References

[edit]- ^ "Short list of Fernandeño Tataviam words". Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians | Language. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

- ^ "Pacoima historian tells the tale of America through the lens of her hometown". Daily News. December 24, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "History of Pacoima". pacoima-history. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ Hsu, Tiffany (September 4, 2014) "Main Street economic renaissance planned for Pacoima". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Los Angeles Times, Mapping LA, Pacoima: 81,318 population in 2008, based on L.A. Department of City Planning estimates. 7.14 square miles. 10,510 people per square mile, about average for the city of Los Angeles and about average for the county.

- ^ a b c d e Meagher, Ed. "Pacoima Area Revamped by Awakened Citizenry." Los Angeles Times. May 18, 1955. A1. Two Pages Local News. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Planners Criticize Pacoima's 'Lack of Pride,' Development." Los Angeles Times. May 22, 1966. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Williams, Timothy. "Poverty, Pride--and Power: In Line for Federal Help, Pacoima Hides Problems Below Neat Surface." Los Angeles Times. April 10, 1994. 3. Retrieved on March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Zipcode 91331". www.plantmaps.com. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ McCawley, William The First Angelinos: The Fernandeno Indians of Mission de Fernndo Ballena Press, 1996 ISBN 0965101606 [1]

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Mural at Pakoinga (Pacoima)". Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Jim Hier (2007). Granada Hills. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-4771-8.

- ^ Carl A. Maida (December 16, 2008). Pathways through Crisis: Urban Risk and Public Culture. AltaMira Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-7591-1245-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Pacoima's History". Pacoima Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Composite: Baist's Map of the San Fernando Valley, Plates 46, 47, 48, 49. - David Rumsey Historical Map Collection". www.davidrumsey.com.

- ^ "Annexation and Detachment Map." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on March 19, 2010.

- ^ Holland, Gale (September 9, 2019). "Locked out of L.A.'s white neighborhoods, they built a black suburb. Now they're homeless". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ Hill, Gladwyn. "7 Die as Planes Collide and One Falls in Schoolyard; PLANES COLLIDE, SCHOOL YARD HIT Roar Alerts Students 'Everything on Fire' Witness Describes Crash", The New York Times, February 1, 1957, Retrieved on February 3, 2010. "Wreckage of airliner falls into school yard at Pacoima, Calif."

- ^ "31-JAN-1957 Douglas DC-7B N8210H." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on February 3, 2010.

- ^ "7 KILLER, 74 HURT IN SCHOOL AIR CRASH." [sic] Los Angeles Times. February 1, 1957. Start page 1. 5 pages. Retrieved on February 3, 2010.

- ^ "Pacoima Boy Dies, 8th Air Crash Victim." Los Angeles Times. February 3, 1957. Start page: 1. 4 pages. Retrieved on February 3, 2010.

- ^ "PLANE SLAMS PACOIMA HOUSE; 4 ABOARD DIE." Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1957. Start page 1, 2 pages. Retrieved on February 3, 2010.

- ^ "Juicy Couture to open store in Ohio Archived 2012-09-28 at the Wayback Machine." The Cincinnati Enquirer. March 15, 2010. Retrieved on March 17, 2010. "Founded in 1996 in Pacoima, Calif., Juicy Couture was purchased by Liz Claiborne Inc. in 2003. Items from the brand can be found at local Nordstrom..."

- ^ "Pacoima neighborhood in Pacoima, California (CA), 91331, 91340 subdivision profile - real estate, apartments, condos, homes, community, population, jobs, income, streets". www.city-data.com.

- ^ "Pacoima Profile - Mapping L.A. - Los Angeles Times".

- ^ [2] "Pacoima", Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ [3] "Community Facts" American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau

- ^ "Foothill Community Police Station." Los Angeles Police Department. Retrieved on March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Fire Station 98 Archived 2010-01-24 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles Fire Department. Retrieved on March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Neighborhood Fire Stations Archived 2010-04-21 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles Fire Department. Retrieved on March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Content Error". Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Pacoima Health Center." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved on March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Post Office Location - PACOIMA." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 6, 2008.

- ^ [4] Mapping L.A.

- ^ "Bus and Rail System Archived 2010-06-21 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ David M. Gonzales Recreation Center.

- ^ a b "Ritchie Valens Park." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Ritchie Valens Recreation Center." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "Ritchie Valens Pool." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Martin, Hugo. "Ritchie Valens Park Nearer Reality Recreation: Council votes to rename a Pacoima site for the late singer. Commission must approve the action". Los Angeles Times. June 4, 1994. Metro Part B Metro Desk. Start Page 3. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ Becker, Tom. "VALLEY FOCUS; Pacoima; Ritchie Valens Fest to Rock the Weekend." Los Angeles Times. May 7, 1998. Metro Part B Metro Desk. Start Page 3. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Hubert H. Humphrey Pool." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Hubert H. Humphrey Memorial Park." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on October 21, 2012.

- ^ "[5]." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on November 15, 2018

- ^ "Golf Course Slated in Pacoima Park." Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1962. Section J, M10. Retrieved on March 19, 2010.

- ^ "Hansen Dam Municipal Golf Course

- ^ "Hansen Dam Golf Contract Signed." Los Angeles Times. June 29, 1962. B11. Retrieved on March 19, 2010.

- ^ "Golf Clubhouse Set at Hansen Dam Course." Los Angeles Times. August 11, 1974. Part VII, G15. Retrieved on March 19, 2010.

- ^ "Roger Jessup Recreation Center." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. "Educational Attainment 25 Years and Over (ACS 5-Year Estimates) - Los Angeles County, California". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- ^ [6] "Pacoima: Schools," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ "11. Proposed Changes to Valley Region High School Zone #5 Zone of Choice Area Schools" (Archive). Los Angeles Unified School District. Retrieved on April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Pacoima Profile." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Pacoima Branch Library." Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Pacoima Library Site Purchase Under Way." Los Angeles Times. April 20, 1958. San Fernando Valley SF8. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "City Board Will Seek Pacoima Library Bids." Los Angeles Times. April 24, 1960. San Fernando Valley. Page SF5. Retrieved on March 18, 2010. "Bids for the construction of a branch library at Van Nuys Blvd. and Haddon Ave. will be asked by the Los Angeles Library Commission late next month."

- ^ "Library in Pacoima to Open Aug. 23." Los Angeles Times. August 13, 1961. Section J Page I4. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "6 New Branch Libraries to Open in 1961." Los Angeles Times. December 22, 1960. E1, 2 pages. Retrieved on March 19, 2010.

- ^ Stassel, Stephanie. "Valley Libraries Branching Out in Building Boom; Services: In a massive citywide project, dozens of facilities will be rebuilt, remodeled and added. Many will be closed during construction." Los Angeles Times. October 2, 2000. Metro Part B Metro Desk. Start Page 1. Retrieved on March 18, 2010. "Pacoima. 13605 Van Nuys Blvd. Estimated cost: $2665500. Description: New 10500- square-foot building and parking to replace existing 5511-square-foot library."

- ^ a b "SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA / A news summary; Groundbreaking Held for Pacoima Library." Los Angeles Times. August 25, 2000. Metro Part B Metro Desk. Start Page 4. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ Willmann, Martha L. "Pacoima Protesters Denounce Library Cutbacks, Demand Service Restoration." Los Angeles Times. June 22, 1978. San Fernando Valley SF2. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ Bond, Ed. "PACOIMA Homework Center Opens at Library." Los Angeles Times. September 16, 1994. Metro Part B Zones Desk. Start Page 3. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ Satzman, Darrell. "VALLEY FOCUS; Pacoima; Use of Grant Funds on 2 Libraries Urged." Los Angeles Times. March 5, 1998. Metro Part B Zones Desk. Start Page 3. Retrieved on March 18, 2010. "Pacoima branch librarian Angelica H. Gracia said the community has outgrown its present library, built in 1961."

- ^ Guzman, Alejandro. "Pacoima Library Serves as Sanctuary." Los Angeles Daily News. September 13, 2006. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ Delgadillo, Sharis. "L.A's Living Legend, Muralist Judy Baca Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine." University of Southern California. November 15, 2009. Retrieved on August 29, 2010.

- ^ Dominguez, Fernando (July 2, 1997). "Boxing Champ Chacon's Life on the Ropes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Aron, Hillel (November 9, 2015). "These Savvy Women Have Made Black Lives Matter the Most Crucial Left-Wing Movement Today". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Orioles vs. Angels - Game Recap - July 6, 2012 - ESPN". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013.

- ^ Roderick, Kevin (July 2002). "Power Play in East Valley". Los Angeles Magazine.

- ^ "DaShon Polk". Pro=Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Shyong, Frank (August 23, 2013). "Pacoima Muralist Uses Paint and Persuasion". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "VOICE OF EXPERIENCE." Daily News of Los Angeles. January 22, 2005. Retrieved on August 29, 2010. "Convictions for robbery and gang violence earned the Pacoima native a..."

External links

[edit]Pacoima, Los Angeles.

- Official Pacoima Neighborhood Council website

- Empowerla.org: Pacoima Neighborhood Council—Department of Neighborhood Empowerment, Pacoima NC webpage

- CRA/LA.org: Pacoima/Panorama City

- Tataviam.org: Tataviam tribal website

- Joangushin.net: "1957 mid-air collision above Pacoima Junior High School"—newspaper clippings