Turkey

Republic of Türkiye Türkiye Cumhuriyeti (Turkish) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: İstiklal Marşı "Independence March"[1] | |

| |

| Capital | Ankara 39°55′N 32°51′E / 39.917°N 32.850°E |

| Largest city | Istanbul 41°1′N 28°57′E / 41.017°N 28.950°E |

| Official languages | Turkish[2][3] |

| Spoken languages |

|

| Ethnic groups (2016)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | |

| Cevdet Yılmaz | |

| Numan Kurtulmuş | |

| Kadir Özkaya | |

| Legislature | Grand National Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| c. 1299 | |

| 19 May 1919 | |

| 23 April 1920 | |

| 1 November 1922 | |

| 24 July 1923 | |

| 29 October 1923 | |

| 9 November 1982[6] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 783,562 km2 (302,535 sq mi) (36th) |

• Water (%) | 2.03[7] |

| Population | |

• December 2023 estimate | |

• Density | 111[8]/km2 (287.5/sq mi) (83rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (45th) |

| Currency | Turkish lira (₺) (TRY) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Calling code | +90 |

| ISO 3166 code | TR |

| Internet TLD | .tr |

Turkey,[a] officially the Republic of Türkiye,[b] is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a smaller part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran to the east; Iraq, Syria, and the Mediterranean Sea to the south; and the Aegean Sea, Greece, and Bulgaria to the west. Turkey is home to over 85 million people; most are ethnic Turks, while ethnic Kurds are the largest ethnic minority.[5] Officially a secular state, Turkey has a Muslim-majority population. Ankara is Turkey's capital and second-largest city, while Istanbul is its largest city and economic and financial center. Other major cities include İzmir, Bursa, and Antalya.

Turkey was first inhabited by modern humans during the Late Paleolithic.[12] Home to important Neolithic sites like Göbekli Tepe and some of the earliest farming areas, present-day Turkey was inhabited by various ancient peoples.[13] The Hattians were assimilated by the Anatolian peoples, such as the Hittites.[14] Classical Anatolia transitioned into cultural Hellenization following the conquests of Alexander the Great; Hellenization continued during the Roman and Byzantine eras.[15] The Seljuk Turks began migrating into Anatolia in the 11th century, starting the Turkification process.[16] The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum ruled Anatolia until the Mongol invasion in 1243, when it disintegrated into Turkish principalities.[17] Beginning in 1299, the Ottomans united the principalities and expanded. Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (now known as Istanbul) in 1453. During the reigns of Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire became a global power.[18][19] From 1789 onwards, the empire saw a major transformation, reforms, and centralization while its territory declined.[20]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, persecution of Muslims during the Ottoman contraction and in the Russian Empire resulted in large-scale loss of life and mass migration into modern-day Turkey from the Balkans, Caucasus, and Crimea.[21] Under the control of the Three Pashas, the Ottoman Empire entered World War I in 1914, during which the Ottoman government committed genocides against its Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian subjects.[22][23][24] Following Ottoman defeat, the Turkish War of Independence resulted in the abolition of the sultanate and the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne. The Republic was proclaimed on 29 October 1923, modelled on the reforms initiated by the country's first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Turkey remained neutral during most of World War II, but was involved in the Korean War. Several military interventions interfered with the transition to a multi-party system.

Turkey is an upper-middle-income and emerging country; its economy is the world's 17th-largest by nominal and 12th-largest by PPP-adjusted GDP. It is a unitary presidential republic. Turkey is a founding member of the OECD, G20, and Organization of Turkic States. With a geopolitically significant location, Turkey is a regional power[25] and an early member of NATO. An EU candidate, Turkey is part of the EU Customs Union, CoE, OIC, and TURKSOY.

Turkey has coastal plains, a high central plateau, and various mountain ranges; its climate is temperate with harsher conditions in the interior.[26] Home to three biodiversity hotspots,[27] Turkey is prone to frequent earthquakes and is highly vulnerable to climate change.[28][29] Turkey has a universal healthcare system, growing access to education, and increasing levels of innovativeness.[30] It is a leading TV content exporter.[31] With 21 UNESCO World Heritage sites, 30 UNESCO intangible cultural heritage inscriptions,[32] and a rich and diverse cuisine,[33] Turkey is the fifth most visited country in the world.

Etymology

Turchia, meaning "the land of the Turks", had begun to be used in European texts for Anatolia by the end of the 12th century.[34][35][36] As a word in Turkic languages, Turk may mean "strong, strength, ripe" or "flourishing, in full strength".[37] It may also mean ripe as in for a fruit or "in the prime of life, young, and vigorous" for a person.[38] As an ethnonym, the etymology is still unknown.[39] In addition to usage in languages such as Chinese in the 6th century,[36] the earliest mention of Turk (𐱅𐰇𐰺𐰜, türü̲k̲; or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚, türk/tẄrk) in Turkic languages comes from the Second Turkic Khaganate.[40]

In Byzantine sources in the 10th century, the name Tourkia was used for defining two medieval states: Hungary (Western Tourkia); and Khazaria (Eastern Tourkia).[41][42] The Mamluk Sultanate, with its ruling elite of Turkic origin, was called the "State of the Turks" (Dawlat at-Turk, or Dawlat al-Atrāk, or Dawlat-at-Turkiyya).[43] Turkestan, also meaning the "land of the Turks", was used for a historic region in Central Asia.[44]

Middle English usage of Turkye or Turkeye is found in The Book of the Duchess (written in 1369–1372) to refer to Anatolia or the Ottoman Empire.[45] The modern spelling Turkey dates back to at least 1719.[46] The bird called turkey was named as such due to trade of guineafowl from Turkey to England.[36] The name Turkey has been used in international treaties referring to the Ottoman Empire.[47] With the Treaty of Alexandropol, the name Türkiye entered international documents for the first time. In the treaty signed with Afghanistan in 1921, the expression Devlet-i Âliyye-i Türkiyye ("Sublime Turkish State") was used, likened to the Ottoman Empire's name.[48]

In December 2021, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called for expanded official usage of Türkiye, saying that Türkiye "represents and expresses the culture, civilization, and values of the Turkish nation in the best way".[49] In May 2022, the Turkish government requested the United Nations and other international organizations to use Türkiye officially in English; the UN agreed.[50][51][52]

History

Prehistory and ancient history

Present-day Turkey has been inhabited by modern humans since the late Paleolithic period and contains some of the world's oldest Neolithic sites.[54][55] Göbekli Tepe is close to 12,000 years old.[54] Parts of Anatolia include the Fertile Crescent, an origin of agriculture.[56] Other important Anatolian Neolithic sites include Çatalhöyük and Alaca Höyük.[57] Neolithic Anatolian farmers differed genetically from farmers in Iran and Jordan Valley.[58] These early Anatolian farmers also migrated into Europe, starting around 9,000 years ago.[59][60][61] Troy's earliest layers go back to around 4500 BC.[57]

Anatolia's historical records start with clay tablets from approximately around 2000 BC that were found in modern-day Kültepe.[62] These tablets belonged to an Assyrian trade colony.[62] The languages in Anatolia at that time included Hattian, Hurrian, Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic.[63] Hattian was a language indigenous to Anatolia, with no known modern-day connections.[63][64] Hurrian language was used in northern Syria.[63] Hittite, Palaic, and Luwian languages were "the oldest written Indo-European languages",[65] forming the Anatolian sub-group.[66][c]

Hattian rulers were gradually replaced by Hittite rulers.[62] The Hittite kingdom was a large kingdom in Central Anatolia, with its capital of Hattusa.[62] It co-existed in Anatolia with Palaians and Luwians, approximately between 1700 and 1200 BC.[62] As the Hittite kingdom was disintegrating, further waves of Indo-European peoples migrated from southeastern Europe, which was followed by warfare.[70] The Thracians were also present in modern-day Turkish Thrace.[71] It is not known if the Trojan War is based on historical events.[72] Troy's Late Bronze Age layers matches most with Iliad's story.[73]

Early classical antiquity

Around 750 BC, Phrygia had been established, with its two centers in Gordium and modern-day Kayseri.[75] Phrygians spoke an Indo-European language, which was closer to Greek than Anatolian languages.[66] Phrygians shared Anatolia with Neo-Hittites and Urartu. Luwian-speakers were probably the majority in various Anatolian Neo-Hittite states.[76] Urartians spoke a non-Indo-European language and their capital was around Lake Van.[77][75] Urartu and Phrygia fell in seventh century BC.[75][78] They were replaced by Carians, Lycians and Lydians.[78] These three cultures "can be considered a reassertion of the ancient, indigenous culture of the Hattian cities of Anatolia".[78]

Before 1200 BC, there were four Greek-speaking settlements in Anatolia, including Miletus.[79] Around 1000 BC, Greeks started migrating to the west coast of Anatolia. These eastern Greek settlements played a vital role in shaping the Archaic Greek civilization;[75][80] important cities included Miletus, Ephesus, Halicarnassus, Smyrna (now İzmir) and Byzantium (now Istanbul), the latter founded by colonists from Megara in the seventh century BCE.[81] These settlements were grouped as Aeolis, Ionia, and Doris, after the specific Greek groups that settled them.[82][83] Further Greek colonization in Anatolia was led by Miletus and Megara in 750–480 BC.[84] The Greek cities along the Aegean prospered with trade, and saw remarkable scientific and scholarly accomplishments.[85] Thales and Anaximander from Miletus founded the Ionian School of philosophy, thereby laying the foundations of rationalism and Western philosophy.[86]

Cyrus attacked eastern Anatolia in 547 BC, and Achaemenid Empire eventually expanded into western Anatolia.[78] In the east, the Armenian province was part of the Achaemenid Empire.[75] Following the Greco-Persian Wars, the Greek city-states of the Anatolian Aegean coast regained independence, but most of the interior stayed part of the Achaemenid Empire.[78] Two of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, and the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, were located in Anatolia.[88]

Following the victories of Alexander in 334 BC and 333 BC, the Achaemenid Empire collapsed and Anatolia became part of the Macedonian Empire.[78] This led to increasing cultural homogeneity and Hellenization of the Anatolian interior,[89][90][91] which met resistance in some places.[92] Following Alexander's death, the Seleucids ruled large parts of Anatolia, while native Anatolian states emerged in the Marmara and Black Sea areas. In eastern Anatolia, the kingdom of Armenia appeared. In third century BC, Celts invaded central Anatolia and continued as a major ethnic group in the area for around 200 years. They were known as the Galatians.[93]

Rome and Byzantine Empire

When Pergamon requested assistance in its conflict with the Seleucids, Rome intervened in Anatolia in the second century BC. Without an heir, Pergamum's king left the kingdom to Rome, which was annexed as province of Asia. Roman influence grew in Anatolia afterwards.[94] Following Asiatic Vespers massacre, and Mithridatic Wars with Pontus, Rome emerged victorious. Around the 1st century BC, Rome expanded into parts of Pontus and Bithynia, while turning rest of Anatolian states into Roman satellites.[95] Several conflicts with Parthians ensued, with peace and wars alternating.[96]

According to Acts of the Apostles, early Christian Church had significant growth in Anatolia because of St Paul's efforts. Letters from St. Paul in Anatolia comprise the oldest Christian literature.[97] Under Roman authority, ecumenical councils such as Council of Nicaea (Iznik) in 325 served as a guide for developing "orthodox expressions of basic Christian teachings".[98]

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centered in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term Byzantine Empire was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as Romans. Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of Christianity as the state religion, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier Roman Empire and the later Byzantine Empire.[citation needed]

In the early Byzantine Empire period, the Anatolian coastal areas were Greek speaking. In addition to natives, interior Anatolia had diverse groups such as Goths, Celts, Persians and Jews. Interior Anatolia had been "heavily Hellenized".[100] Anatolian languages eventually became extinct after Hellenization of Anatolia.[101]

Seljuks and Anatolian beyliks

According to historians and linguists, the Proto-Turkic language originated in Central-East Asia.[102] Initially, Proto-Turkic speakers were potentially both hunter-gatherers and farmers; they later became nomadic pastoralists.[103] Early and medieval Turkic groups exhibited a wide range of both East Asian and West-Eurasian physical appearances and genetic origins, in part through long-term contact with neighboring peoples such as Iranic, Mongolic, Tocharian, Uralic, and Yeniseian peoples.[104] During the 9th and 10th centuries CE, the Oghuz were a Turkic group that lived in the Caspian and Aral steppes.[105] Partly due to pressure from the Kipchaks, the Oghuz migrated into Iran and Transoxiana.[105] They mixed with Iranic-speaking groups in the area and converted to Islam.[105] Oghuz Turks were also known as Turkoman.[105]

The Seljuks originated from the Kınık branch of the Oghuz Turks who resided in the Yabgu Khaganate.[106] In 1040, the Seljuks defeated the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Dandanaqan and established the Seljuk Empire in Greater Khorasan.[107] Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliphate's capital and center of the Islamic world, was taken by Seljuks in 1055.[108] Given the role Khurasani traditions played in art, culture, and political traditions in the empire, the Seljuk period is described as a mixture of "Turkish, Persian and Islamic influences".[109] In the latter half of the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks began penetrating into medieval Armenia and Anatolia.[108] At the time, Anatolia was a diverse and largely Greek-speaking region after previously being Hellenized.[110][111][100]

The Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and later established the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum.[112] During this period, there were also Turkish principalities such as Danishmendids.[113] Seljuk arrival started the Turkification process in Anatolia;[111][114] there were Turkic/Turkish migrations, intermarriages, and conversions into Islam.[115][116] The shift took several centuries and happened gradually.[117][118] Members of Islamic mysticism orders, such as Mevlevi Order, played a role in the Islamization of the diverse people of Anatolia.[119][120] Seljuk expansion was one of the reasons for the Crusades.[121] In 13th century, there was a second significant wave of Turkic migration, as people fled Mongol expansion.[122][123] Seljuk sultanate was defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 and disappeared by the beginning of the 14th century. It was replaced by various Turkish principalities.[17][124]

Ottoman Empire

Based around Söğüt, Ottoman Beylik was founded by Osman I in the early 14th century.[125] According to Ottoman chroniclers, Osman descended from the Kayı tribe of the Oghuz Turks.[126] Ottomans started annexing the nearby Turkish beyliks (principalities) in Anatolia and expanded into the Balkans.[127] Mehmed II completed Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine Empire by capturing its capital, Constantinople, on 29 May 1453.[128] Selim I united Anatolia under Ottoman rule.[18] Turkification continued as Ottomans mixed with various indigenous people in Anatolia and the Balkans.[126]

The Ottoman Empire was a global power during the reigns of Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent.[18][19] In the 16th and 17th centuries, Sephardic Jews moved into Ottoman Empire following their expulsion from Spain.[129] From the second half of the 18th century onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to decline. The Tanzimat reforms, initiated by Mahmud II in 1839, aimed to modernize the Ottoman state in line with the progress that had been made in Western Europe. The Ottoman constitution of 1876 was the first among Muslim states, but was short-lived.[130][131]

As the empire gradually shrank in size, military power and wealth; especially after the Ottoman economic crisis and default in 1875[134] which led to uprisings in the Balkan provinces that culminated in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). The decline of the Ottoman Empire led to a rise in nationalist sentiment among its various subject peoples, leading to increased ethnic tensions which occasionally burst into violence, such as the Hamidian massacres of Armenians, which claimed up to 300,000 lives.[135][better source needed] Ottoman territories in Europe (Rumelia) were lost in the First Balkan War (1912–1913).[136] Ottomans managed to recover some territory in Europe, such as Edirne, in the Second Balkan War (1913).

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, persecution of Muslims during the Ottoman contraction and in the Russian Empire resulted in estimated 5 million deaths,[137][138] with the casualties including Turks.[138] Five to seven or seven to nine million refugees migrated into modern-day Turkey from the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Mediterranean islands,[139] shifting the center of the Ottoman Empire to Anatolia.[140] In addition to a small number of Jews, the refugees were overwhelmingly Muslim; they were both Turkish and non-Turkish people, such as Circassians and Crimean Tatars.[141][142] Paul Mojzes has called the Balkan Wars an "unrecognized genocide", where multiple sides were both victims and perpetrators.[143] Circassian refugees included the survivors of the Circassian genocide.[144]

Following the 1913 coup d'état, the Three Pashas took control of the Ottoman government. The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated.[145] During the war, the empire's Armenian subjects were deported to Syria as part of the Armenian genocide. As a result, an estimated 600,000[146] to more than 1 million,[146] or up to 1.5 million[147][148][149] Armenians were killed. The Turkish government has refused to acknowledge[22][150] the events as genocide and states that Armenians were only "relocated" from the eastern war zone.[151] Genocidal campaigns were also committed against the empire's other minority groups such as the Assyrians and Greeks.[152][153][154] Following the Armistice of Mudros in 1918, the victorious Allied Powers sought the partition of the Ottoman Empire through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.[155]

Republic of Türkiye

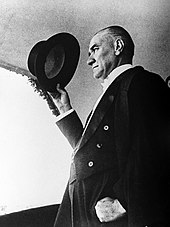

The occupation of Istanbul (1918) and İzmir (1919) by the Allies in the aftermath of World War I initiated the Turkish National Movement. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920).[156]

The Turkish Provisional Government in Ankara, which had declared itself the legitimate government of the country on 23 April 1920, started to formalize the legal transition from the old Ottoman into the new Republican political system. The Ankara Government engaged in armed and diplomatic struggle. In 1921–1923, the Armenian, Greek, French, and British armies had been expelled.[157][158][159][160] The military advance and diplomatic success of the Ankara Government resulted in the signing of the Armistice of Mudanya on 11 October 1922. On 1 November 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate, thus ending 623 years of monarchical Ottoman rule.

The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres,[155][156] led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the new Turkish state as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire. On 4 October 1923, the Allied occupation of Turkey ended with the withdrawal of the last Allied troops from Istanbul. The Turkish Republic was officially proclaimed on 29 October 1923 in Ankara, the country's new capital.[161] The Lausanne Convention stipulated a population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[162]

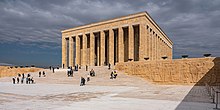

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first president and introduced many reforms. The reforms aimed to transform the old religion-based and multi-communal Ottoman monarchy into a Turkish nation state that would be governed as a parliamentary republic under a secular constitution.[163] Women gained the right to vote nationally in 1934.[164] With the Surname Law, the Turkish Parliament bestowed upon Kemal the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father Turk).[156] Atatürk's reforms caused discontent in some Kurdish and Zaza tribes leading to the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925[165] and the Dersim rebellion in 1937.[166]

İsmet İnönü became the country's second president following Atatürk's death in 1938. In 1939, the Republic of Hatay voted in favor of joining Turkey with a referendum. Turkey remained neutral during almost all of World War II,[167] but entered the war on the side of the Allies on 23 February 1945.[168] Later that year, Turkey became a charter member of the United Nations.[169] In 1950 Turkey became a member of the Council of Europe. After fighting as part of the UN forces in the Korean War, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, becoming a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean.

Military coups or memorandums, which happened in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997, complicated Turkey's transition to a democratic multiparty system.[170][171] Between 1960 and the end of the 20th century, the prominent leaders in Turkish politics who achieved multiple election victories were Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit and Turgut Özal.[citation needed] PKK started a "campaign of terrorist attacks on civilian and military targets" in the 1980s.[172] It is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey,[173] the United States,[174] and the European Union.[175] Tansu Çiller became the first female prime minister of Turkey in 1993. Turkey applied for full membership of the EEC in 1987, joined the European Union Customs Union in 1995 and started accession negotiations with the European Union in 2005.[176][177] Customs Union had an important impact on the Turkish manufacturing sector.[178][179]

In 2014, prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won Turkey's first direct presidential election.[180] On 15 July 2016, an unsuccessful coup attempt tried to oust the government.[181] According to the Turkish government, there are 13,251 arrested or convicted people in jail as of 2024, related to the 2016 coup attempt.[182][183] With a referendum in 2017, the parliamentary republic was replaced by an executive presidential system. The office of the prime minister was abolished, and its powers and duties were transferred to the president. On the referendum day, while the voting was still underway, the Supreme Electoral Council lifted a rule that required each ballot to have an official stamp.[184] The opposition parties claimed that as many as 2.5 million ballots without a stamp were accepted as valid.[184]

Administrative divisions

Turkey has a unitary structure in terms of public administration, and the provinces are subordinate to the central government in Ankara. In province centers the government is represented by the province governors (vali) and in towns by the governors (kaymakam). Other senior public officials are also appointed by the central government, except for the mayors (belediye başkanı) who are elected by the constituents.[185] Turkish municipalities have local legislative bodies (belediye meclisi) for decision-making on municipal issues.

Turkey is subdivided into 81 provinces (il or vilayet) for administrative purposes. Each province is divided into districts (ilçe), for a total of 973 districts.[186] Turkey is also subdivided into 7 regions (bölge) and 21 subregions for geographic, demographic and economic measurements, surveys and classifications; this does not refer to an administrative division.

Government and politics

Turkey is a presidential republic within a multi-party system.[187] The current constitution was adopted in 1982.[188] In the Turkish unitary system, citizens are subject to three levels of government: national, provincial, and local. The local government's duties are commonly split between municipal governments and districts, in which the executive and legislative officials are elected by a plurality vote of citizens by district.[citation needed] The government comprises three branches: first is the legislative branch, which is Grand National Assembly of Turkey;[189] second is the executive branch, which is the President of Turkey;[190] and third is the judicial branch, which includes the Constitutional Court, the Court of Cassation and Court of Jurisdictional Disputes.[191][6]

The Parliament has 600 seats, distributed among the provinces proportionally to the population. The Parliament and the president serve a five-year terms, with elections on the same day. The president is elected by direct vote and cannot run for re-election after two terms, unless the parliament calls early presidential elections during the second term.[citation needed] The Constitutional Court is composed of 15 members, elected for single 12-year terms. They are obliged to retire when they are over the age of 65.[192] Turkish politics have become increasingly associated with democratic backsliding, being described as a competitive authoritarian system.[193][194]

Parties and elections

Elections in Turkey are held for six functions of government: presidential (national), parliamentary (national), municipality mayors (local), district mayors (local), provincial or municipal council members (local), and muhtars (local). Referendums are also held occasionally. Every Turkish citizen who has turned 18 has the right to vote and stand as a candidate at elections.[citation needed] Universal suffrage for both sexes has been applied throughout Turkey since 1934.[195] In Turkey, turnout rates of both local and general elections are high compared to many other countries, which usually stands higher than 80%.[citation needed] President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is currently serving as the head of state and head of government.[196][197] Özgür Özel is the Main Opposition Leader. The last parliamentary and presidential elections were in 2023.

The Constitutional Court can strip the public financing of political parties that it deems anti-secular or having ties to terrorism, or ban their existence altogether.[198][199] The electoral threshold for political parties at national level is seven percent of the votes.[200] Smaller parties can avoid the electoral threshold by forming an alliance with other parties. Independent candidates are not subject to an electoral threshold.

On the right side of the Turkish political spectrum, parties like the Democrat Party, Justice Party, Motherland Party, and Justice and Development Party became the most popular political parties in Turkey, winning numerous elections. Turkish right-wing parties are more likely to embrace the principles of political ideologies such as conservatism, nationalism or Islamism.[201] On the left side of the spectrum, parties like the Republican People's Party, Social Democratic Populist Party and Democratic Left Party once enjoyed the largest electoral success. Left-wing parties are more likely to embrace the principles of socialism, Kemalism or secularism.[202]

Law

With the founding of the Republic, Turkey adopted a civil law legal system, replacing Sharia-derived Ottoman law. The Civil Code, adopted in 1926, was based on the Swiss Civil Code of 1907 and the Swiss Code of Obligations of 1911. Although it underwent a number of changes in 2002, it retains much of the basis of the original Code. The Criminal Code, originally based on the Italian Criminal Code, was replaced in 2005 by a Code with principles similar to the German Penal Code and German law generally. Administrative law is based on the French equivalent and procedural law generally shows the influence of the Swiss, German and French legal systems.[203] Islamic principles do not play a part in the legal system.[204]

Law enforcement in Turkey is carried out by several agencies under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. These agencies are the General Directorate of Security, the Gendarmerie General Command and the Coast Guard Command.[205] In the years of government by the Justice and Development Party and Erdoğan, particularly since 2013, the independence and integrity of the Turkish judiciary has increasingly been said to be in doubt by institutions, parliamentarians and journalists both within and outside of Turkey, because of political interference in the promotion of judges and prosecutors and in their pursuit of public duty.[206][207][208]

Foreign relations

Turkey's constant foreign policy goal is to pursue its national interests. These interests are mainly growing the economy, and maintaining security from internal terrorist and external threats.[209] After the establishment of the Republic, Atatürk and İnönü followed the "peace at home, peace in the world" principle until the Cold War's start.[210] Following threats from the Soviet Union, Turkey sought to ally with the United States and joined NATO in 1952.[211][212] Overall, Turkey aims for good relations with Central Asia, the Caucasus, Russia, the Middle East, and Iran. With the West, Turkey also aims to keep its arrangements.[213] By trading with the east and joining the EU, Turkey pursues economic growth.[213] Turkey joined the European Union Customs Union in 1995,[214] but its EU accession talks are frozen as of 2024.[215]

Turkey has been called an emerging power,[216] a middle power,[217] and a regional power.[218] Turkey has sought closer relations with the Central Asian Turkic states after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[219] Closer relations with Azerbaijan, a culturally close country, was achieved.[219] Turkey is a founding member of the International Organization of Turkic Culture and Organization of Turkic States.[220][221] It is also a member of Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Council of Europe, and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[222]

Following the Arab Spring, Turkey had problems with countries such as United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.[223] Relations with these countries have improved since then.[223][224][225] The exception is Syria, with which Turkey had cut its relations after the start of the Syrian civil war.[226] There are disputes with Greece over maritime boundaries and with Cyprus.[227]

In 2018, the Turkish military and the Turkish-backed forces began an operation in Syria aimed at ousting US-backed YPG (which Turkey considers to be an offshoot of the outlawed PKK)[228][229] from the enclave of Afrin.[230][231] Turkey has also conducted airstrikes in Iraqi Kurdistan, which was criticized by Iraq for violating its sovereignty and killing civilians.[232] Diplomatic relations with Israel were damaged after the Gaza flotilla raid,[233] normalized in 2016,[234] and cut again following the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip.[235] In 2024, Turkey stopped trading with Israel.[235]

Military

Turkish Armed Forces is responsible for defense against foreign threats. While the Commander-in-Chief is the President, General Staff, Air Force, Naval Force, and Land Force usually report to the Minister of National Defence.[239] The Gendarmerie General Command and the Coast Guard Command are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior.[240] Military service is required for 6–12 months for men,[241] which is reduced to one month after paying a fee.[242] Turkey does not recognize conscientious objection and does not offer a civilian alternative to military service.[243]

Turkey has the second-largest standing military force in NATO, after the United States, with an estimated strength of 890,700 military personnel as of February 2022.[244] As part of the nuclear sharing policy of NATO, Turkey hosts approximately 20 United States B61 nuclear bombs at the Incirlik Air Base.[245][246] The Turkish Armed Forces have a relatively substantial military presence abroad,[247] with military bases in Albania,[248] Iraq,[249] Qatar,[250] and Somalia.[251] The country also maintains a force of 36,000 troops in Northern Cyprus since 1974.[252]

Turkey has participated in international missions under the United Nations and NATO since the Korean War, including peacekeeping missions in Somalia, Yugoslavia and the Horn of Africa. It supported coalition forces in the First Gulf War, contributed military personnel to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, and remains active in Kosovo Force, Eurocorps and EU Battlegroups.[253][254] As of 2016, Turkey has assisted Peshmerga forces in northern Iraq and the Somali Armed Forces with security and training.[255][256]

Human rights

Article 2 of the Turkish Constitution includes references to upholding the rule of law and human rights.[258] In the 2000s, legal changes were made for public use of and teaching in the Kurdish language. This included opening a Kurdish-language national TV channel. Various "openings" were made to address concerns of minorities such as Alevi, ethnic Kurds, and ethnic Romani people.[259] Sentences for violence against women were strengthened.[259]

In 2013, widespread protests erupted, sparked by a plan to demolish Gezi Park but soon growing into general anti-government dissent.[260] On 20 May 2016, the Turkish parliament stripped almost a quarter of its members of immunity from prosecution, including 101 deputies from the pro-Kurdish HDP and the main opposition CHP party.[261][262] According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, there are 13 jailed journalists in Turkey.[263] In its 2023 report, the European Commission criticized how democratic institutions in Turkey operate.[264] The criticism was rejected by Turkey.[265] As of 2023, Turkey was the country with the highest number of European Court of Human Rights cases.[266]

Prior to 1858, Ottoman Empire had "a lenient legal accommodation of same-sex intimacy". When prosecuted, the punishment was monetary fines. In 1858, the 1810 French Penal Code was adopted by the Ottomans, which had no penalties for same-sex intimacy that is private.[268] Under the Republic, same sex acts have never been criminalized.[269] However, LGBT people in Turkey face discrimination, harassment and even violence.[270] In a survey conducted in 2016, 33% of respondents said that LGBT people should have equal rights, which increased to 45% in 2020. Another survey in 2018 found that the proportion of people who would not want a homosexual neighbor decreased from 55% in 2018 to 47% in 2019.[271][272]

When the annual Istanbul Pride was inaugurated in 2003, Turkey became the first Muslim-majority country to hold a gay pride march.[273] Since 2015, parades at Taksim Square and İstiklal Avenue have been denied government permission, citing security concerns, but hundreds of people have defied the ban each year.[267] The bans were criticized.[267]

Geography

Turkey covers an area of 783,562 square kilometres (302,535 square miles).[274] With Turkish straits and Sea of Marmara in between, Turkey bridges Western Asia and Southeastern Europe.[275] Turkey's Asian side covers 97% of its surface, and is often called Anatolia.[276] Another definition of Anatolia's eastern boundary is an imprecise line from the Black Sea to Gulf of Iskenderun.[277] Eastern Thrace, Turkey's European side, includes around 10% of the population and covers 3% of the surface area.[278] The country is encircled by seas on three sides: the Aegean Sea to the west, the Black Sea to the north and the Mediterranean Sea to the south.[279] Turkey is bordered by Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran to the east.[279] To the south, it's bordered by Syria and Iraq.[280] To the north, its Thracian area is bordered by Greece and Bulgaria.[279]

Turkey is divided into "seven major regions": Marmara, Aegean, Central Anatolia, Black Sea, Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia and the Mediterranean.[279] As a general trend, the inland Anatolian Plateau becomes increasingly rugged as it progresses eastward.[281] Mountain ranges include Köroğlu and Pontic mountain ranges to the north, and the Taurus Mountains to the south. The Lakes Region contains some of the largest lakes in Turkey such as Lake Beyşehir and Lake Eğirdir.

Geographers have used the eastern Anatolian plateau, Iranian plateau, and Armenian plateau terms to refer to the mountainous area around where Arabian and Eurasian tectonic plates merge. The eastern Anatolian plateau and Armenian plateau definitions largely overlap.[283] The Eastern Anatolia Region contains Mount Ararat, Turkey's highest point at 5,137 metres (16,854 feet),[284] and Lake Van, the largest lake in the country.[285] Eastern Turkey is home to the sources of rivers such as the Euphrates, Tigris and Aras. The Southeastern Anatolia Region includes the northern plains of Upper Mesopotamia.

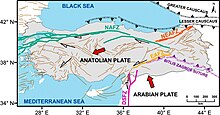

Earthquakes happen frequently in Turkey.[28] Almost the entire population lives in areas with varying seismic risk levels, with around 70% in highest or second-highest seismic areas.[286][287] Anatolian plate is bordered by North Anatolian Fault zone to the north; East Anatolian Fault zone and Bitlis–Zagros collision zone to the east; Hellenic and Cyprus subduction zones to the south; and Aegean extensional zone to the west.[288] After 1999 İzmit and 1999 Düzce earthquakes, North Anatolian Fault zone activity "is considered to be one of the most dangerous natural hazards in Turkey".[289] 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquakes were the deadliest in contemporary Turkish history.[290] Turkey is sometimes unfavorably compared to Chile, a country with a similar developmental level that is more successful with earthquake preparedness.[291][292][293]

Biodiversity

Turkey's position at the crossroads of the land, sea and air routes between the three Old World continents and the variety of the habitats across its geographical regions have produced considerable species diversity and a vibrant ecosystem.[294] Out of the 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world, Turkey includes 3 of them.[27] These are the Mediterranean, Irano-Anatolian, and Caucasus hotspots.[27]

The forests of Turkey are home to the Turkey oak. The most commonly found species of the genus Platanus (plane) is the orientalis. The Turkish pine (Pinus brutia) is mostly found in Turkey and other east Mediterranean countries. Several wild species of tulip are native to Anatolia, and the flower was first introduced to Western Europe with species taken from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.[295][296]

There are 40 national parks, 189 nature parks, 31 nature preserve areas, 80 wildlife protection areas and 109 nature monuments in Turkey such as Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park, Mount Nemrut National Park, Ancient Troy National Park, Ölüdeniz Nature Park and Polonezköy Nature Park.[297] The Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests is an ecoregion which covers most of the Pontic Mountains in northern Turkey, while the Caucasus mixed forests extend across the eastern end of the range. The region is home to Eurasian wildlife such as the Eurasian sparrowhawk, golden eagle, eastern imperial eagle, lesser spotted eagle, Caucasian black grouse, red-fronted serin, and wallcreeper.[298]

The Anatolian leopard is still found in very small numbers in the northeastern and southeastern regions of Turkey.[299][300] The Eurasian lynx, the European wildcat and the caracal are other felid species which are found in the forests of Turkey. The Caspian tiger, now extinct, lived in the easternmost regions of Turkey until the latter half of the 20th century.[299][301] Renowned domestic animals from Ankara include the Angora cat, Angora rabbit and Angora goat; and from Van Province the Van cat. The national dog breeds are the Kangal (Anatolian Shepherd), Malaklı and Akbaş.[302]

Climate

The coastal areas of Turkey bordering the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas have a temperate Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild to cool, wet winters.[304] The coastal areas bordering the Black Sea have a temperate oceanic climate with warm, wet summers and cool to cold, wet winters.[304] The Turkish Black Sea coast receives the most precipitation and is the only region of Turkey that receives high precipitation throughout the year.[304] The eastern part of the Black Sea coast averages 2,200 millimetres (87 in) annually which is the highest precipitation in the country.[304] The coastal areas bordering the Sea of Marmara, which connects the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea, have a transitional climate between a temperate Mediterranean climate and a temperate oceanic climate with warm to hot, moderately dry summers and cool to cold, wet winters.[304]

Snow falls on the coastal areas of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea almost every winter but usually melts in no more than a few days.[304] However, snow is rare in the coastal areas of the Aegean Sea and very rare in the coastal areas of the Mediterranean Sea.[304] Winters on the Anatolian plateau are especially severe. Temperatures of −30 to −40 °C (−22 to −40 °F) do occur in northeastern Anatolia, and snow may lie on the ground for at least 120 days of the year, and during the entire year on the summits of the highest mountains. In central Anatolia the temperatures can drop below −20 °C (−4 °F) with the mountains being even colder. Mountains close to the coast prevent Mediterranean influences from extending inland, giving the central Anatolian Plateau a continental climate with sharply contrasting seasons.[304]

Due to socioeconomic, climatic, and geographic factors, Turkey is highly vulnerable to climate change.[29] This applies to nine out of ten climate vulnerability dimensions, such as "average annual risk to wellbeing".[29] OECD median is two out of ten.[29] Inclusive and swift growth is needed for decreasing vulnerability.[305] Turkey aims to achieve net zero emissions by 2053.[306] Accomplishing climate goals would require large investments, but would also result in net economic benefits, broadly due to reduced imports of fuel and due to better health from lowering air pollution.[307]

|

Economy

Turkey is an upper-middle-income country and an emerging market.[287][314] A founding member of the OECD and G20, it is the 17th-largest economy by nominal and the 12th-largest economy by PPP-adjusted GDP in the world.[315] It is classified among newly industrialized countries. Services account for the majority of GDP, whereas industry accounts for more than 30%.[316] Agriculture contributes about 7%.[316] According to IMF estimates, Turkey's GDP per capita by PPP is $40,283 in 2024, while its nominal GDP per capita is $15,666.[315] Foreign direct investment in Turkey peaked at $22.05 billion in 2007 and dropped to $13.09 billion in 2022.[317] Potential growth is weakened by long-lasting structural and macro obstacles, such as slow rates of productivity growth and high inflation.[287]

Turkey has a diversified economy; main industries include automobiles, electronics, textiles, construction, steel, mining, and food processing.[316] It is a major agricultural producer.[322] Turkey ranks 8th in crude steel production, and 13th in motor vehicle production, ship building (by tonnage), and annual industrial robot installation in the world.[323] Turkish automative companies include TEMSA, Otokar, BMC and Togg. Togg is the first all-electric vehicle company of Turkey. Arçelik, Vestel, and Beko are major manufacturers of consumer electronics.[324] Arçelik is one of the largest producers of household goods in the world.[325] In 2022, Turkey ranked second in the world in terms of the number of international contractors in the top 250 list.[326] It is also the fifth largest in the world in terms of textile exports.[327] Turkish Airlines is one of the largest airlines in the world.

Between 2007 and 2021, the share of population below the PPP-$6.85 per day international poverty threshold declined from 20% to 7.6%.[287] In 2023, 13.9% of the population was below the national at-risk-of-poverty rate.[329] In 2021, 34% of the population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, using Eurostat definition.[330] Unemployment in Turkey was 10.4% in 2022.[331] In 2021, it was estimated that 47% of total disposable income was received by the top 20% of income earners, while the lowest 20% received only 6%.[332]

Tourism accounts for about 8% of Turkey's GDP.[333] In 2022, Turkey ranked fifth in the world in the number of international tourist arrivals with 50.5 million foreign tourists.[334] Turkey has 21 UNESCO World Heritage Sites and 84 World Heritage Sites in tentative list. Turkey is home to 519 Blue Flag beaches, third most in the world.[335] According to Euromonitor International report, Istanbul is the most visited city in the world, with more than 20.2 million foreign visitors in 2023.[328] Antalya has surpassed Paris and New York to become the fourth most visited city in the world, with more than 16.5 million foreign visitors.[328]

Infrastructure

Turkey is the 16th largest electricity producer in the world. Turkey's energy generation capacity increased significantly, with electricity generation from renewable sources tripling in the past decade.[337][338] It produced 43.8% of its electricity from such sources in 2019.[339] Turkey is also the fourth-largest producer of geothermal power in the world.[340] Turkey's first nuclear power station, Akkuyu, will increase diversification of its energy mix.[341] When it comes to total final consumption, fossil fuels still play a large role, accounting for 73%.[342] A major reason of Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions is the large proportion of coal in the energy system.[343] As of 2017, while the government had invested in low carbon energy transition, fossil fuels were still subsidized.[344] By 2053, Turkey aims to have net zero emissions.[306]

Turkey has made security of its energy supply a top priority, given its heavy reliance on gas and oil imports.[341] Turkey's main energy supply sources are Russia, West Asia, and Central Asia.[213] Gas production began in 2023 in the recently discovered Sakarya gas field. When fully operational, it will supply about 30% of the natural gas needed domestically.[345][346] Turkey aims to become a hub for regional energy transportation.[347] Several oil and gas pipelines span the country, including the Blue Stream, TurkStream, and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipelines.[347]

As of 2023, Turkey has 3,726 kilometers of controlled-access highways and 29,373 kilometers of divided highways.[348] Multiple bridges and tunnels connect Asian and European sides of Turkey; the Çanakkale 1915 Bridge on the Dardanelles strait is the longest suspension bridge in the world.[349] Marmaray and Eurasia tunnels under the Bosporus connect both sides of Istanbul.[350] The Osman Gazi Bridge connects the northern and southern shores of the Gulf of İzmit.

Turkish State Railways operates both conventional and high speed trains, with the government expanding both.[351] High-speed rail lines include the Ankara-Istanbul, Ankara-Konya, and Ankara-Sivas routes.[352] Istanbul Metro is the largest subway network in the country with around 704 million annual ridership in 2019.[353] There are 115 airports as of 2024.[354] Istanbul Airport is one of the top 10 busiest airports in the world. Turkey aims to become a transportation hub.[355][356] It is part of various routes that connect Asia and Europe, including the Middle Corridor.[356] In 2024, Turkey, Iraq, UAE, and Qatar signed an agreement to link Iraqi port facilities to Turkey via road and rail connections.[357]

Science and technology

Turkey's spending on research and development as a share of GDP has risen from 0.47% in 2000 to 1.40% in 2021.[358] Turkey ranks 16th in the world in terms of article output in scientific and technical journals, and 35th in Nature Index.[359][360] Turkish patent office ranks 21st worldwide in overall patent applications, and 3rd in industrial design applications. Vast majority of applicants to the Turkish patent office are Turkish residents. In all patent offices globally, Turkish residents rank 21st for overall patent applications.[361] In 2024, Turkey ranked 37th in the world and 3rd among its upper-middle income group in the Global Innovation Index.[362]

TÜBİTAK is one of the main agencies for funding and carrying out research.[363][364] Turkey's space program plans to develop a national satellite launch system, and to improve capabilities in space exploration, astronomy, and satellite communication.[364] Under the Göktürk Program, Turkish Space Systems, Integration and Test Center was built.[365] Turkey's first communication satellite manufactured domestically, Türksat 6A, will be launched in 2024.[366] As part of a planned particle accelerator center, an electron accelerator called TARLA became operational in 2024.[367][368] An Antarctic research station is planned on Horseshoe Island.[369]

Turkey is considered a significant power in unmanned aerial vehicles.[370] Aselsan, Turkish Aerospace Industries, Roketsan, and Asfat are among the top 100 defense companies in the world.[371] Turkish defense companies spend a significant portion of their budgets for research and development.[372] Aselsan also invests in research in quantum technology.[373]

Demographics

According to the Address-Based Population Recording System, the country's population was 85,372,377 in 2023, excluding Syrians under temporary protection.[8] 93% lived in province and district centers.[8] People within the 15–64 and 0–14 age groups corresponded to 68.3% and 21.4% of the total population, respectively. Those aged 65 years or older made up 10.2%.[8] Between 1950 and 2020, Turkey's population more than quadrupled from 20.9 million to 83.6 million;[375] however, the population growth rate was 0.1% in 2023.[8] In 2023, the total fertility rate was 1.51 children per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.10 per woman.[376] In a 2018 health survey, the ideal children number was 2.8 children per woman, rising to 3 per married woman.[377]

Ethnicity and language

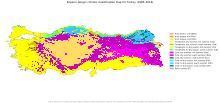

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a Turk as anyone who is a citizen.[379] It is estimated that there are at least 47 ethnic groups represented in Turkey.[380] Reliable data on the ethnic mix of the population is not available because census figures do not include statistics on ethnicity after the 1965 Turkish census.[381] According to the World Factbook, 70–75% of the country's citizens are ethnic Turks.[5] Based on a survey, KONDA's estimation was 76% in 2006, with 78% of adult citizens self-identifying their ethnic background as Turk.[382] In 2021, 77% of adult citizens identified as such in a survey.[383]

Kurds are the largest ethnic minority.[384] Their exact numbers remain disputed,[384] with estimates ranging from 12 to 20% of the population.[385] According to a 1990 study, Kurds made up around 12% of the population.[386] The Kurds make up a majority in the provinces of Ağrı, Batman, Bingöl, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Hakkari, Iğdır, Mardin, Muş, Siirt, Şırnak, Tunceli and Van; a near majority in Şanlıurfa (47%); and a large minority in Kars (20%).[387] In addition, internal migration has resulted in Kurdish diaspora communities in all of the major cities in central and western Turkey. In Istanbul, there are an estimated three million Kurds, making it the city with the largest Kurdish population in the world.[388] 19% of adult citizens identified as ethnic Kurds in a survey in 2021.[383] Some people have multiple ethnic identities, such as both Turk and Kurd.[389][390] In 2006, an estimated 2.7 million ethnic Turks and Kurds were related from interethnic marriages.[391]

According to the World Factbook, non-Kurdish ethnic minorities are 7–12% of the population.[5] In 2006, KONDA estimated that non-Kurdish and non-Zaza ethnic minorities constituted 8.2% of the population; these were people that gave general descriptions such as Turkish citizen, people with other Turkic backgrounds, Arabs, and others.[382] In 2021, 4% of adult citizens identified as non-ethnic Turk or non-ethnic Kurd in a survey.[383] According to the Constitutional Court, there are only four officially recognized minorities in Turkey: the three non-Muslim minorities recognized in the Treaty of Lausanne (Armenians, Greeks, and Jews[d]) and the Bulgarians.[e][395][396][397] In 2013, the Ankara 13th Circuit Administrative Court ruled that the minority provisions of the Lausanne Treaty should also apply to Assyrians in Turkey and the Syriac language.[398][399][400] Other unrecognized ethnic groups include Albanians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Georgians, Laz, Pomaks, and Roma.[401][402][403]

The official language is Turkish, which is the most widely spoken Turkic language in the world.[404][405] It is spoken by 85%[406][407] to 90%[408] of the population as a first language. Kurdish speakers are the largest linguistic minority.[408] A survey estimated 13% of the population speak Kurdish or Zaza as a first language.[406] Other minority languages include Arabic, Caucasian languages, and Gagauz.[408] The linguistic rights of the officially recognized minorities are de jure recognized and protected for Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Hebrew,[f][392][395][396][397] and Syriac.[399][400] There are multiple endangered languages in Turkey.

Largest cities or towns in Turkey

TÜİK's address-based calculation from 31 December 2023 published at 7th of February 2024. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Pop. | Rank | Name | Pop. | ||||

Istanbul  Ankara |

1 | Istanbul | 15,655,924 | 11 | Mersin | 1,938,389 |  İzmir  Bursa | ||

| 2 | Ankara | 5,803,482 | 12 | Diyarbakır | 1,818,133 | ||||

| 3 | İzmir | 4,479,525 | 13 | Hatay | 1,544,640 | ||||

| 4 | Bursa | 3,214,571 | 14 | Manisa | 1,475,716 | ||||

| 5 | Antalya | 2,696,249 | 15 | Kayseri | 1,445,683 | ||||

| 6 | Konya | 2,320,241 | 16 | Samsun | 1,377,546 | ||||

| 7 | Adana | 2,270,298 | 17 | Balıkesir | 1,273,519 | ||||

| 8 | Şanlıurfa | 2,213,964 | 18 | Tekirdağ | 1,167,059 | ||||

| 9 | Gaziantep | 2,164,134 | 19 | Aydın | 1,161,702 | ||||

| 10 | Kocaeli | 2,102,907 | 20 | Van | 1,127,612 | ||||

Immigration

Excluding Syrians under temporary protection, there were 1,570,543 foreign citizens in Turkey in 2023.[8] Millions of Kurds fled across the mountains to Turkey and the Kurdish areas of Iran during the Gulf War in 1991. Turkey's migrant crisis in the 2010s and early 2020s resulted in the influx of millions of refugees and immigrants.[409] Turkey hosts the largest number of refugees in the world as of April 2020.[410] The Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency manages the refugee crisis in Turkey. Before the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the estimated number of Arabs in Turkey varied from 1 million to more than 2 million.[411]

In November 2020, there were 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey;[412] these included other ethnic groups of Syria, such as Syrian Kurds[413] and Syrian Turkmens.[414] As of August 2023, the number these refugees was estimated to be 3.3 million. The number of Syrians had decreased by about 200,000 people since the beginning of the year.[415] The government has granted citizenship to 238 thousand Syrians by November 2023.[416] As of May 2023, approximately 96,000 Ukrainian refugees of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine have sought refuge in Turkey.[417] In 2022, nearly 100,000 Russian citizens migrated to Turkey, becoming the first in the list of foreigners who moved to Turkey, meaning an increase of more than 218% from 2021.[418]

Religion

Turkey is a secular state with no official state religion; the constitution provides for freedom of religion and conscience.[422][423] According to the CIA World Factbook, Muslims constitute 99.8% of the population, most of them being Sunni.[5] Based on a survey, KONDA's estimate for Muslims was 99.4% in 2006.[424] According to Minority Rights Group International, estimates of share of Alevi are between 10% and 40% of the population.[425] KONDA's estimate was 5% in 2006.[424] 4% of adult citizens identified as Alevi in a survey in 2021, while 88% identified as Sunni.[383]

The percentage of non-Muslims in modern-day Turkey was 19.1% in 1914, but fell to 2.5% in 1927.[426] Currently, non-Muslims constitute 0.2% of the population according to the World Factbook.[5] In 2006, KONDA's estimate was 0.18% for people with non-Islam religions.[424] Some of the non-Muslim communities are Armenians, Assyrians, Bulgarian Orthodox, Catholics, Chaldeans, Greeks, Jews, and Protestants.[427] Sources estimate that the Christian population in Turkey ranges between 180,000 and 320,000.[428][429] Turkey has the largest Jewish community among the Muslim-majority countries.[430] Currently, there are 439 churches and synagogues in Turkey.[431]

In 2006, KONDA's estimate was 0.47% for those with no religion.[424] According to KONDA, share of adult citizens who identified as unbeliever increased from 2% in 2011 to 6% in 2021.[383] A 2020 Gezici Araştırma poll found that 28.5% of the Generation Z identify as irreligious.[432][433]

Education

In the past 20 years, Turkey has improved quality of education and has made significant progress in increasing education access.[435] From 2011 to 2021, improvements in education access include "one of the largest increases in educational attainment for 25-34 year-olds at upper secondary non-tertiary or tertiary education", and quadrupling of pre-school institutions.[436] PISA results suggest improvements in education quality.[436] There is still a gap with OECD countries. Significant challenges include differences in student outcomes from different schools, differences between rural and urban areas, pre-primary education access, and arrival of students who are Syrian refugees.[436]

The Ministry of National Education is responsible for pre-tertiary education.[438] Compulsory education is free at public schools and lasts 12 years, divided into three parts.[439][435] There are 208 universities in Turkey.[364] Students are placed to universities based on their YKS results and their preferences, by the Measuring, Selection and Placement Center.[440] All state and private universities are under the control of the Higher Education Board (Turkish: Yükseköğretim Kurulu, YÖK). Since 2016, the president of Turkey directly appoints all rectors of all state and private universities.[441]

According to the 2024 Times Higher Education ranking, the top universities were Koç University, Middle East Technical University, Sabancı University, and Istanbul Technical University.[442] According to Academic Ranking of World Universities, the top ones were Istanbul University, University of Health Sciences (Turkey), and Hacettepe University.[443] Turkey is a member of the Erasmus+ Programme.[444] Turkey has become a hub for foreign students in recent years, with 795,962 foreign students in 2016.[445] In 2021 Türkiye Scholarships, a government-funded program, received 165,000 applications from prospective students in 178 countries.[446][447][448]

Health

The Ministry of Health has run a universal public healthcare system since 2003.[450] Known as Universal Health Insurance (Genel Sağlık Sigortası), it is funded by a tax surcharge on employers, currently at 5%.[450] Public-sector funding covers approximately 75.2% of health expenditures.[450] Despite the universal health care, total expenditure on health as a share of GDP in 2018 was the lowest among OECD countries at 6.3% of GDP, compared to the OECD average of 9.3%.[450] There are many private hospitals in the country.[451] The government planned several hospital complexes, known as city hospitals, to be constructed since 2013.[451] Turkey is one of the top 10 destinations for health tourism.[452]

Average life expectancy is 78.6 years (75.9 for males and 81.3 for females), compared with the EU average of 81 years.[450] Turkey has high rates of obesity, with 29.5% of its adult population having a body mass index (BMI) value of 30 or above.[453] Air pollution is a major cause of early death.[454]

Culture

In the 19th century, Turkish identity was debated in the Ottoman Empire, with three main views: Turkism, Islamism and Westernism.[455] In addition to Europe or Islam, Turkish culture was also influenced by Anatolia's native cultures.[456] After the establishment of the republic, Kemalism emphasized Turkish culture, attempted to make "Islam a matter of personal conviction", and pursued modernization.[457] Currently, Turkey has various local cultures. Things such as music, folk dance, or kebap variety may be used to identify a local area. Turkey also has a national culture, such as national sports leagues, music bands, film stars, and trends in fashion.[458]

Literature, theatre, and visual arts

Turkish literature goes back more than a thousand years. The Seljuk and Ottoman periods include numerous works of literature and poetry. Turkic tales and poetry from Central Asia were also kept alive. Tales of Dede Korkut is an example of the oral narrative tradition. Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, from the 11th century, contains Turkish linguistic information and poetry. Yunus Emre, influenced by Rumi, was one of the most important writers of Anatolian Turkish poetry. Ottoman Divan poetry used "refined diction" and complex vocabulary. It included Sufi mysticism, romanticism, and formal elements.[459]

Beginning in the 19th century, Ottoman literature was influenced by the West. New genres, such as novels and journalistic style, were introduced. Aşk-ı Memnu, written by Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil, was the "first truly refined Turkish novel". Fatma Aliye Topuz, the first female Turkish novelist, wrote fiction. After the proclamation of the republic in 1923, Atatürk instituted reforms such as the language reform and alphabet reform. Since then, Turkish literature reflected the socioeconomic conditions in Turkey with increasing variety. "Village Novel" genre appeared in the mid-1950s, which talked about difficulties faced from poverty.[459] An example is Memed, My Hawk by Yaşar Kemal, which was Turkey's first Nobel Prize in Literature nominee in 1973.[459][460] Orhan Pamuk won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature.[459]

Turkey has four "major theatrical traditions": "folk theatre, popular theatre, court theater, and Western theater." Turkish folk theatre goes back thousands of years and has survived among rural communities. Popular theatre includes plays by live actors, puppet and shadow plays, and storytelling performances. An example for shadow play is Karagöz and Hacivat. Court theatre was the refined version of popular theatre. Beginning in the 19th century, Western theatre tradition started appearing in Turkey. Following the establishment of Turkish Republic, a state conservatory and the State Theatre Company were formed.[461]

Turkey's visual arts scene can be categorized into two, as "decorative" and "fine" arts. Fine arts, or güzel sanatlar, includes sculpture and painting. Turkish artists in these areas have gained global recognition. Photography, fashion design, graphic arts, and graphic design are some of the other areas Turkish artists are known for in the world. The inaugural contemporary Turkish art sale by Sotheby's London was in 2009. Istanbul Modern and the Istanbul Biennial are examples of art galleries or exhibitions of contemporary Turkish art. Turkey has also seen a resurgence of traditional arts. This includes Ottoman-era traditional arts, such as ceramics and carpets. Textile and carpet design, glass and ceramics, calligraphy, paper marbling (ebru) are some of the art forms for which modern-day Turkish artists are recognized as leaders in the Islamic world.[462]

Music and dance

Although classifying genres of Turkish music can be problematic, three broad categories can be considered. These are "Turkish folk music", "Turkish art music", and multiple popular music styles. These Popular music styles include arabesque, pop, and Anatolian rock.[463]

The resurging popularity of pop music gave rise to several international Turkish pop stars such as Ajda Pekkan, Sezen Aksu, Erol Evgin, MFÖ, Tarkan, Sertab Erener, Teoman, Kenan Doğulu, Levent Yüksel and Hande Yener.[citation needed] Internationally acclaimed Turkish jazz and blues musicians and composers include Ahmet Ertegun[464] (founder and president of Atlantic Records), Nükhet Ruacan and Kerem Görsev.[citation needed]

Architecture

Turkey is home to numerous Neolithic settlements, such as Çatalhöyük.[466][57] From the Bronze Age, important architectural remnants include Alaca Höyük and the 2nd layer of Troy.[57] There are various examples of Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman architectures, especially in the Aegean region.[467] Byzantine architecture dates back to the 4th century AD. Its best example is Hagia Sophia. Byzantine architectural style continued to develop after the conquest of Istanbul, such as Byzantine Revival architecture.[468] During Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and Turkish principalities period, a distinct architecture emerged, which incorporated Byzantine and Armenian architectures with architectural styles found in West Asia and Central Asia.[469] Seljuk architecture often used stones and bricks, and produced numerous caravanserais, madrasas and mausoleums.[470]

Ottoman architecture emerged in northwest Anatolia and Thrace. Early Ottoman architecture mixed "traditional Anatolian Islamic architecture with local building materials and techniques".[471] Following the conquest of Istanbul, classical Ottoman architecture emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries.[472] The most important architect of the classical period is Mimar Sinan, whose major works include the Şehzade Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, and Selimiye Mosque.[472] Beginning in the 18th century, Ottoman architecture was influenced by European elements, resulting in development of Ottoman baroque style.[473] European influence continued in the 19th century; examples include works of Balyan family such as neo-Baroque style Dolmabahçe Palace.[474] The last period of Ottoman architecture consists of the First National Architectural Movement, including works of Vedat Tek and Mimar Kemaleddin.[473]

Since 1918, Turkish architecture can be divided into three parts. From 1918 to 1950, the first one includes the First National Architectural Movement period, which transitioned into modernist architecture. Modernist and monumental buildings were preferred for public buildings, whereas "Turkish house" type vernacular architecture influenced private houses. From 1950 to 1980, the second part includes urbanization, modernization, and internationalization. For residential housing, "reinforced concrete, slab-block, medium-rise apartments" became prevalent. Since 1980, the third part is defined by consumer habits and international trends, such as shopping malls and office towers. Luxury residences with "Turkish house style" have been in demand.[475] In the 21st century, urban renewal projects have become a trend.[476] Resilience against natural disasters such as earthquakes is one of the main goals for urban renewal projects.[477] Around one-third of Turkey's building stock, corresponding to 6.7 million units, were assessed risky and needing urban renewal.[478]

Cuisine

Turkey has a diverse and rich cuisine, varying geographically.[33] Turkish cuisine has been influenced by Anatolian, Mediterranean, Iranian, Central Asian, and East Asian cuisines.[481] Turkish and Ottoman cuisine have also influenced others. Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, from the 11th century, documents "the ancient lineage of much of present-day Turkish cuisine".[481] Güveç, Bulgur, and Börek are some of the earliest recorded examples of Turkish cuisine. Even though kebab as a word comes from Persian, Turkic people had been familiar with using skewers to cook meat. Turkish cuisine can be distinguished by its various kinds of kebabs. Similarly, pilaf dishes were influenced by Turkish cuisine. Further information about cuisine during the Seljuk and Ottoman periods comes from the works of Rumi and Evliya Çelebi. The latter describes "food-related guilds of Istanbul".[481]

Food staples in Turkey include bread and yogurt. Some of bread varieties are lavash and pide (a type of pita bread). Ayran is a drink made of yoghurt. In western parts of Turkey, olive oil is used. Grains include wheat, maize, barley, oats, and millet. Beans, chickpeas, nuts, aubergines, and lamb are some of the commonly used ingredients.[481] Doner kebab, originally from Turkey, is marinated lamb slices cooked vertically.[482] Seafood includes anchovy and others. Dolma varieties and mantı are made by stuffing vegetables or pasta.[481] Sarma is made by rolling edible leaf over the filling.[483] Yahni dishes are vegetable stews.[481] Turkey is one of the countries with the meze tradition.[484] Honey, pekmez, dried fruit, or fruit are used for sweetening.[481] Filo is an originally Turkish dough that is used to make baklava.[485] Turkish delight is a "delicate but gummy jelly".[486]

Sports

The most popular sport is association football.[487] Galatasaray won the UEFA Cup and UEFA Super Cup in 2000.[488] The Turkey national football team won the bronze medal at the 2002 FIFA World Cup, the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup and UEFA Euro 2008.[489]

Other mainstream sports such as basketball and volleyball are also popular.[490] The men's national basketball team and women's national basketball team have been successful. Anadolu Efes S.K. is the most successful Turkish basketball club in international competitions.[491][492] Fenerbahçe reached the final of the EuroLeague in three consecutive seasons (2015–2016, 2016–2017 and 2017–2018), becoming the European champions in 2017.

The final of the 2013–14 EuroLeague Women basketball championship was played between two Turkish teams, Galatasaray and Fenerbahçe, and won by Galatasaray.[493] Fenerbahçe won the 2023 FIBA Europe SuperCup Women after two consecutive Euroleague wins in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 seasons.

The women's national volleyball team has won several medals.[494] Women's volleyball clubs, namely VakıfBank S.K., Fenerbahçe and Eczacıbaşı, have won numerous European championship titles and medals.[495]

The traditional national sport of Turkey has been yağlı güreş (oil wrestling) since Ottoman times.[496] Edirne Province has hosted the annual Kırkpınar oil wrestling tournament since 1361, making it the oldest continuously held sporting competition in the world.[497][498] In the 19th and early 20th centuries, oil wrestling champions such as Koca Yusuf, Nurullah Hasan and Kızılcıklı Mahmut acquired international fame in Europe and North America by winning world heavyweight wrestling championship titles. International wrestling styles governed by FILA such as freestyle wrestling and Greco-Roman wrestling are also popular, with many European, World and Olympic championship titles won by Turkish wrestlers both individually and as a national team.[499]

Media and cinema

Hundreds of television channels, thousands of local and national radio stations, several dozen newspapers, a productive and profitable national cinema and a rapid growth of broadband Internet use constitute a vibrant media industry in Turkey.[500][501] The majority of the TV audiences are shared among public broadcaster TRT and the network-style channels such as Kanal D, Show TV, ATV and Star TV. The broadcast media have a very high penetration as satellite dishes and cable systems are widely available.[502] The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) is the government body overseeing the broadcast media.[502][503] By circulation, the most popular newspapers are Posta, Hürriyet, Sözcü, Sabah and Habertürk.[504]

Filiz Akın, Fatma Girik, Hülya Koçyiğit, and Türkan Şoray represent their period of Turkish cinema.[505] Turkish directors like Metin Erksan, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Yılmaz Güney, Zeki Demirkubuz and Ferzan Özpetek won numerous international awards such as the Palme d'Or and Golden Bear.[506] Turkish television dramas are increasingly becoming popular beyond Turkey's borders and are among the country's most vital exports, both in terms of profit and public relations.[507] After sweeping the Middle East's television market over the past decade, Turkish shows have aired in more than a dozen South and Central American countries in 2016.[508][509] Turkey is today the world's second largest exporter of television series.[510][511][512]

See also

Notes

- ^ Turkish: Türkiye, Turkish: [ˈtyɾcije]

- ^ Turkish: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, Turkish: [ˈtyɾcije dʒumˈhuːɾijeti] ⓘ

- ^ The origin of Indo-European languages is unknown.[67] They may be native to Anatolia[68] or non-native.[69]

- ^ Even though they are not explicitly mentioned in the Treaty of Lausanne.[392]

- ^ The Bulgarian community in Turkey is now so small that this disposition is de facto not applied.[392][393][394]

- ^ The Turkish government considers that, for the purpose of the Treaty of Lausanne, the language of Turkish Jews is Hebrew, even though the mother tongue of Turkish Jews was not Hebrew but historically Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino) or other Jewish languages.[396][397]

References

- ^ "The Turkish Flag and The Turkish National Anthem (Independence March)". Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası" (in Turkish). Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

3. Madde: Devletin Bütünlüğü, Resmi Dili, Bayrağı, Milli Marşı ve Başkenti: Türkiye Devleti, ülkesi ve milletiyle bölünmez bir bütündür. Dili Türkçedir. Bayrağı, şekli kanununda belirtilen, beyaz ay yıldızlı al bayraktır. Milli marşı "İstiklal Marşı" dır. Başkenti Ankara'dır.

- ^ "Mevzuat: Anayasa" (in Turkish). Constitutional Court of Turkey. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^

- KONDA 2006, p. 19

- Kornfilt 2018, p. 537

- ^ a b c d e f "Turkey (Turkiye)". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Turkish Constitution". Anayasa Mahkemesi. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2023". www.tuik.gov.tr. Turkish Statistical Institute. 6 February 2024. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Türkiye)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 22 October 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Gini index (World Bank estimate) – Turkey". World Bank. 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Howard 2016, p. 24

- ^

- Howard 2016, pp. 24–28: "Göbekli Tepe’s close proximity to several very early sites of grain cultivation helped lead Schmidt to the conclusion that it was the need to maintain the ritual center that first encouraged the beginnings of settled agriculture—the Neolithic Revolution"

- McMahon & Steadman 2012a, pp. 3–12

- Matthews 2012, p. 49

- ^

- Ahmed 2006, p. 1576: "Turkey’s diversity is derived from its central location near the world’s earliest civilizations as well as a history replete with population movements and invasions. The Hattite culture was prominent during the Bronze Age prior to 2000 BCE, but was replaced by the Indo-European Hittites who conquered Anatolia by the second millennium. Meanwhile, Turkish Thrace came to be dominated by another Indo-European group, the Thracians for whom the region is named."

- Steadman 2012, p. 234: "By the time of the Old Assyrian Colony period in the early second millennium b.c.e . (see Michel, chapter 13 in this volume) the languages spoken on the plateau included Hattian, an indigenous Anatolian language, Hurrian (spoken in northern Syria), and Indo-European languages known as Luwian, Hittite, and Palaic"

- Michel 2012, p. 327

- Melchert 2012, p. 713

- Howard 2016, p. 26

- ^