The Velvet Underground (album)

| The Velvet Underground | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | March 1969 | |||

| Recorded | November–December 1968 | |||

| Studio | TTG, Hollywood | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 43:53 | |||

| Label | MGM | |||

| Producer | The Velvet Underground | |||

| The Velvet Underground chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Velvet Underground | ||||

| ||||

The Velvet Underground is the third studio album by the American rock band the Velvet Underground. Released in March 1969 by MGM Records, it was their first record with multi-instrumentalist Doug Yule, who replaced previous member John Cale. Recorded in 1968 at TTG Studios in Los Angeles, California, the album's sound—consisting largely of ballads and straightforward rock songs—marked a notable shift in style from the band's previous recordings. Lead vocalist Lou Reed intentionally did this as a result of their abrasive previous studio album White Light/White Heat (1968).[6] Reed wanted other band members to sing on the album; Yule contributed lead vocals to the opening track "Candy Says" and the closing track "After Hours" is sung by drummer Maureen Tucker.

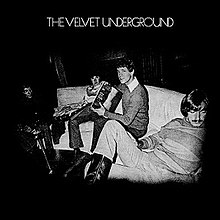

Thematically, The Velvet Underground discusses love, contrasting previous releases from the band. Reed devised its track order and based his songwriting upon relationships and religion. "Pale Blue Eyes" has been hailed as one of his best love songs,[by whom?] although "The Murder Mystery" is noted for its experimentation in a call-back to White Light/White Heat. Billy Name took the album's photograph of the band sitting on a couch at Andy Warhol's Factory. The recording process started at short notice and while the band had a high morale, they were ultimately disappointed that Reed had created his own mix of the final product.

Contemporary reviews praised the album, which was a turning point for the band. Nevertheless, The Velvet Underground failed to chart, again suffering from a lack of promotion by the band's record label. Reed played a dominant role in the mixing process and his own mix of the album, dubbed the "closet mix", was first released in the United States. MGM Director of Engineering Val Valentin was credited for a different mix which has been more widely distributed since then. Retrospective reviews have labeled it one of the greatest albums of the 1960s and of all time, with many critics noting its subdued production and personal lyrics. In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked it at number 143 on its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time".

Background

[edit]Cale was fired from the group in September 1968, and Yule was brought in as a bassist. Yule was discovered by Morrison through the band's road manager Hans Onsager.[7] Weeks after Yule joined the Velvet Underground, they began recording their third studio album.[8] Lou Reed, the band's principal songwriter, believed that the band should not "make another White Light/White Heat. I thought it would be a terrible mistake, and I really believed that. I thought we had to demonstrate the other side of us. Otherwise, we would become this one-dimensional thing, and that had to be avoided at all costs."[6]

According to Morrison, earlier in 1968 a majority of the band's equipment got stolen at JFK International Airport which influenced the album's sound. However, Yule rejects this claim, explaining that he has no recollection of such an event, clarifying that the band was simply playing more melodically—Tucker also says this. Reed during this time had a growing taste for soothing music; in an interview with Lester Bangs he singled out tracks "Jesus" and "Candy Says", declaring the latter "probably the best song I've written ..."[8] Reed considered White Light/White Heat to be as far as the band could go with such production and additionally called each album the band made a chapter.[5] They started recording after touring in the West Coast and band manager Steve Sesnick obtained studio time at a short notice, so the band had provided little time to prepare.[9] At the time, Reed was managing relationships between his girlfriend Shelley Albin and Name, which influenced his songwriting.[10]

Recording

[edit]The Velvet Underground was recorded during November and through December 1968 at TTG Studios in Los Angeles. The band stayed at the hotel Chateau Marmont and toured frequently while recording.[8] They wrote and rehearsed at the hotel in the afternoon, recording songs at night.[11] Reed and Morrison played 12-string guitars from Fender.[8][11] Morale in the studio was generally high—Yule said that recording the album "was a lot of fun. The sessions were constructive and happy and creative, everybody was working together".[6] According to Yule, it took "a couple of weeks for the basic tracks", additionally describing it as a "studio live album". Reed intentionally tried to get Yule in the spotlight of it, and the band members suspected that this might have inflated his ego. Generally, the sessions had a happy atmosphere;[12] Tucker said that she "was pleased with the direction we were going and with the new calmness in the group, and thinking about a good future, hoping people would smarten up and some record company would take us on and do us justice."[6]

"The Murder Mystery" includes all four members' voices. Yule states that the song was recorded in an MGM studio on Sixth Avenue in New York, though this contradicts the record's liner notes.[8] The album's closing song, "After Hours", has a rare solo lead vocal by Tucker, requested by Reed as he felt the sweet, innocent quality of her voice fitted the song's mood better than his own.[13] Tucker was nervous while recording the track, and after eight takes made everyone leave except herself, Reed, and the engineer. After she finished her take, she said that she wouldn't sing it live unless someone requested it. Reed recorded multiple guitar solos for "What Goes On"; when the engineer commented on how they were running out of track space, the band ultimately decided to keep all of them,[8] as Reed could not decide which one sounded better.[14] When Reed did his own mix for the album—which drowned out other backing parts except his vocals—Morrison and Tucker were annoyed.[11] Morrison described the final product as "anti-production".[14]

Music and lyrics

[edit]The restraint and subtlety of the album was a significant departure from the direct abrasiveness of White Light/White Heat.[15][16] It reduced their previous effort's explicit sexual references, horror, and references to drugs, replacing those with discussions of religion, love, and loneliness.[12] Music critic Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune characterized it as folk rock,[17][18] and Rolling Stone magazine's Troy Carpenter said that it focused on mellow, melodic rock.[15] According to music journalist Steve Taylor, The Velvet Underground is a pop album because of its more accessible songs and "has been called Lou Reed with a backing band due to the emphasis placed on songs rather than experimental sound work."[19] Biographer Richie Unterberger commented on its dramatic shift in sound: "Having made perhaps the loudest album of all time, it's almost as if they've now decided to make the world's quietest LP."[8] Reed said that all of the songs on the album were in order and complement each other, elaborating in an interview with Howard Smith:[5]

There were certain questions stated in the opening song ... and then it was delineated, you know, through various phases. ... it ended with 'Jesus,' saying now help me do this, man. ... And then after you went through all ... from here to here, which is like what an average person goes through, you're faced with like 'The Murder Mystery,' which is a total reversal of everything. Because you shouldn't be faced with that, but you were.

Just like on the other albums ... people didn't catch [the track order]. And on this one, I felt it was obvious. But maybe it wasn't. ... And finally he sums up, he says, 'That's the Story of My Life.' But then he was faced with something else, which is once you get past you, you got you solved, so that you don't exist ... But what really is going on outside you is 'The Murder Mystery ... then after that, it was just kind of, well, 'After Hours.' What could you say after 'The Murder Mystery'? Except that 'you close the door, the night could last forever.' Which is true.

Reed considered each song to be impersonal "little plays".[8] Apart from the forceful rockers "What Goes On" and "Beginning to See the Light", the album contains reflective, melodic songs that are about various forms of love,[16] such as "Pale Blue Eyes", "Some Kinda Love", "Jesus", "I'm Set Free" and "That's the Story of My Life". Reed and Morrison's twin-guitar playing became the band's most prominent sound,[16] and the album had spare arrangements that lacked distortion. The only song that exhibited the band's avant-garde roots is "The Murder Mystery".[16] The song took two sessions to record, and its poem was later included in The Paris Review.[14]

Side one

[edit]Opening track "Candy Says" is based on transgender actress Candy Darling who was a member of Warhol's Factory.[13][8] Yule sings a tale of Darling, who hates her body and is in emotional pain.[12] It references Darling's thoughts by ambiguously stating "I've come to hate my body/And all that it requires in this world".[20] Darling reappears in Reed's 1972 song "Walk on the Wild Side".[21] Morrison says that the choice for Yule singing the song was because Reed was worn down by touring. Yule is backed by doo-wop-style harmonies and backing vocals. This was Yule's first time singing in a studio,[8] and the song was sung by Yule at Reed's insistence.[21]

"What Goes On" is upbeat and combines multiple lead guitar parts against an organ; this organ, played by Yule, is present in more songs on the record.[8] Kory Grow of Rolling Stone described Reed's guitar solo on the song as "bagpipe-y".[14] Described as the "anomaly" of side one by Rob Jovanovic, it is complete with a "twitchy beat", its sound as a result of Reed increasing the volume of his guitar during recording.[12] R.C. Baker of The Village Voice labeled this song "one of rock 'n' roll's greatest existential anthems".[22]

"Some Kinda Love" contains salacious lyrics, contrasting the record, but it still has subdued elements—Tucker only uses a cowbell and bass drum.[8] It ambiguously describes love, specifically religious love.[12] Reed references "The Hollow Men" by T.S. Eliot.[13] He writes about two characters, Tom and Marguerita, detailing a seductive conversation between them.[23] Victor Bockris cites this as another example "where [Reed] makes rock lyrics function as literature".[24] Grow said that the song explains how love is uniform, while "Pale Blue Eyes" simply discussed "another kind of love", specifically adultery, according to Reed.[14]

"Pale Blue Eyes" has been called one of Reed's greatest love songs[according to whom?]—Morrison singled it out from the album in a 1981 interview.[citation needed] The composition of it dates back to 1966;[8] it had been performed live since mid-1966.[25] It describes adultery and sinning as an extension of the album's religious references.[12] It was inspired by Reed's girlfriend at the time, Shelley Albin.[26] According to Reed, he wrote it for someone he missed who had hazel eyes; it references "I'll Be Your Mirror" and Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me by Richard Fariña.[13] Additionally, Sesnick speculates that some lines are about Cale's firing.[27] Tucker plays a tambourine.[23] Reed praised Morrison's guitar solo in the song:[8]

It had that beautiful stutter in it. I could never do that. I always wondered how the hell he did that. But it was just the way he played – intuitive, but intuitive matched with brain.

According to Reed, "Jesus" has nothing to do with religion, though he described it as a search song. However, in the folk ballad, Reed asks Jesus for redemption in the form of a joyous sermon.[8] Reed had little interest in religion; the message of the song is generally secular.[23] During the course of the song Yule's bass takes on a lead role in the instrumental backing.[12]

Side two

[edit]"Beginning to See the Light" uses a phrase associated with religious redemption. In the song, Reed discusses his imagined revelation,[8] and affirms his distinction of being loved,[24] this time being described in relation to religion.[14] He addresses the free love movement with the lines "Here we go again/I thought you were my friend", later commenting "How does it feel to be loved?"[28]

"I'm Set Free" is ambiguous, though it salutes Phil Spector; the goodbyes at the end of the song imitate those in "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" by Spector's band the Righteous Brothers.[original research?] Unterberger praises the guitar solo of it as "one of the group's most tastefully underrated".[8] In the song, Reed claims that he is free from a relationship,[14] though he eventually discovers that this is untrue.[24]

"That's the Story of My Life" is minimal in instrumentation. Originally, Cale played viola for the song in live versions, though no viola was included for this studio version.[8] During the song four lines of lyrics are repeated, and refer to Billy Name.[12] The title and lyrics were inspired by a remark from Name, who introduced Reed to one of his largest influences, Alice Bailey.[23] Bockris summarizes the theme of this song: "The difference between right and wrong is the story of [Reed]'s life."[24]

"The Murder Mystery" is a spoken word track.[8] It incorporates a raga rhythm, murmuring organ, overlapping spoken-word passages, and lilting counterpoint vocals.[16] During the verses, Lou Reed and guitarist Sterling Morrison recite different verses of poetry simultaneously, with the voices positioned strictly to the left and right. For the choruses, Tucker and Yule sing different lyrics and melodies at the same time, also separated left and right.[8] Unterberger noted that it has "little melody", and its narrative is repetitive, comparing it to "78rpm and 16rpm records played simultaneously", the track closing with "progressively crazed" piano. Of the song, Reed referenced "Sister Ray", elaborating that the song “is part of the novel that's a murder mystery”. It was never performed live in its entirety—Morrison elaborated that it would be too hard to play.[8] Jovanovic described it as an "incomprehensible mix" and homage to White Light/White Heat; Reed labeled it as a failure, as he wanted "one vocal to be saying the [lyrical] opposite of the other".[12]

"After Hours" was the band's only release at the time with Tucker singing lead vocals. She does not play percussion and is only backed by a guitar and bass. Tucker counts off by saying "one, two, three"; an older recording disk labeled the track "If You Close the Door (Moe's Song)".[8] Generally, the song discusses intentional isolation.[14]

Cover artwork

[edit]The cover was taken by Billy Name, photographer and archivist of Warhol's Factory,[29] featuring the band sitting sedately on a couch at The Factory. Name was paid 300 dollars for the photograph, which was the most he had been paid at the time for a picture.[5] Yule and Tucker are looking at Reed, and Morrison is looking away—according to Tucker, this is because Reed was talking about the magazine cover.[24] The back cover is a picture of Reed smoking, divided in two halves with one of them upside down, both only showing the left side of his face. Each side includes the track listing and credits for the record, which are also upside down in that part of the picture.[5] Reed held an issue of Harper's Bazaar which was airbrushed out.[12] The cover artwork led to the record being dubbed "The Grey Album".[28]

Release

[edit]

The release date of the band's "third album" was given in a November 1968 article in Los Angeles Free Press as January 1969;[30] the full album was previewed by Danish magazine Superlove in January 1969. Phil Morris of MGM told Record World on February 22, 1969, that the album was ready for release. When the album was released in March 1969, the songwriting credits listed the entire band as its composer, even though Reed wrote all of its songs. Later releases would instead label Reed as the sole composer. The band switched from Verve Records to parent label MGM for unknown reasons—Sesnick says that the rock division of Verve was close to closing, while Morrison says that this simply was "an administrative change".[5] Ultimately, the decision to move to MGM was Sesnick's.[24]

Two mixes of the album were released. The initial mix is Reed's which boosts his vocals and lowers its instruments, which was the first mix sold in the United States. Morrison noted that it sounds like it was recorded in a closet, which led to its label as the "closet mix". Valentin produced a more conventional mix, which Yule would later say he was unaware of.[5] The more widely distributed mix is the one credited to Valentin,[12] which was distributed throughout Europe.[23] The two versions use entirely different performances of "Some Kinda Love", both taken from the same recording sessions. The closet mix was chosen for inclusion in the box set Peel Slowly and See.[26]

While Onsager didn't plan on touring until after two commercially successful singles were released, their touring schedule remained nearly uninterrupted, and only one unsuccessful single was released. "What Goes On" was released in March 1969, with "Jesus" as its B side. MGM promoted it in a full-page advertisement in Cashbox but its distribution was heavily limited. The album suffered from lack of promotion, though a radio ad was used for WNEW-FM in New York, and MGM also listed advertisements in publications such as Rolling Stone, Creem, and the Village Voice. Ultimately it failed to chart on the Billboard Top LPs chart, the band's first record to do so. Tucker attributed it to lack of promotion, while Yule noted how the album was ultimately not mainstream.[5] Due to its failure to chart, MGM was not planning on releasing another album from the band.[23]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| The Village Voice | A[31] |

| Record Mirror | |

Unterberger noted how The Velvet Underground sounded far more commercial than any of the band's previous albums and labeled it as the point where critical reception of the band became more positive.[5] Despite this, however, the album failed to chart, and was less successful than the group's previous two.[14] Reviewing the album for The Village Voice in 1969, Robert Christgau viewed it as the band's best work and found it tuneful, well written, and exceptionally sung, despite "another bummer experiment" in "The Murder Mystery" and some "mystery" regarding the mix.[31] In his ballot for Jazz & Pop magazine's annual critics poll, Christgau ranked it as the sixth best album of the year.[32] He later included it in his "Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings, published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[33]

Lester Bangs, writing in Rolling Stone magazine, felt that it is not on-par with White Light/White Heat and has missteps with "The Murder Mystery" and "Pale Blue Eyes", but ultimately said that its combination of powerfully expressive music and profoundly sentimental lyrics will persuade the band's detractors into believing they can "write and play any kind of music they want to with equal brilliance."[34] Paul Williams of Crawdaddy declared that "everybody loves" the band's new release and labeled it his personal favorite since Forever Changes by Love. Bob Stark for Creem observed how it was "as 'far out' as either of the two [previous albums]". Lenny Kaye reviewed the record for Jazz & Pop, labeling it "almost lyrical in its beauty." Other newspapers such as Chicago Seed, Record World, Cashbox, and the more mainstream Variety praised the album, with the latter stating that it is "an important contribution to the lyrical advancement of rock". Adrian Ribolla of Oz, however, lamented that the "Velvet Underground don't really sound together on this album". Additionally, Broadside from Massachusetts longed for the older sound of the band.[5] Melody Maker, while praising the album, simultaneously dismissed it by commenting it is "not sensational, but interesting". Retrospectively in October 1969, Richard Williams of the same magazine elaborated that "the old cruelty was still there", labeling the old Melody Maker review as erroneous and hailing the band's first three albums as "a body of work which is easily as impressive as any in rock".[35]

Reappraisal

[edit]| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 98/100 (super deluxe)[36] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[40] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 10/10[44] |

The Velvet Underground did not impact the Billboard 200 until its 1985 reissue, when it reached No. 197.[45] According to Billboard in 2013, The Velvet Underground has sold 201,000 copies since 1991, when Nielsen SoundScan began tracking record sales.[45]

In a review of the album's 1985 reissue, Rolling Stone's David Fricke remarked that both The Velvet Underground and its predecessor lack the diverse range of the band's 1967 debut album and the precise accessibility of Loaded (1970). However, he felt that the album is still edifying as a tender, subtly broad song cycle whose stark production surprisingly reveals the essence of Reed's more expressive songwriting. Fricke cited the "ironic pairing" of "Pale Blue Eyes" and "Jesus" as the best summary of "the hopeful warmth at the center of the Velvets' rage."[42]

Professional reviewers hailed the album's subdued production. Colin Larkin, writing in The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (1998), said that the album showcased a new subtlety because of Reed's larger role in the band and that it "unveiled a pastoral approach, gentler and more subdued, retaining the chilling, disquieting aura of previous releases."[46] In The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), Rob Sheffield wrote that after Cale's departure, the band became "acoustic folkie balladeers" and that Reed was unexpectedly charming on the album, whose "every song is a classic".[43] Q magazine called the album "a flickering, unforgettable band performance".[41] Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune highlighted Reed's subdued contribution to the record, summarizing it as "for the first time without John Cale, [Reed] creates quiet, impossibly beautiful folk-rock."[17] Mark Deming for AllMusic wrote that the songs on the record are the most personal and moving that the band had recorded.[37] Brian Eno declared it his favorite album from the band.[5]

Rankings

[edit]The Velvet Underground was voted number 262 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[47] In 2003, it was ranked number 314 by Rolling Stone on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. The 2012 edition saw it dropped to 316, and the 2020 edition moved it up to 143.[48][49][50] NME magazine named it the 21st best album of all time in a list of the 100 Best Albums of All Time.[51] Pitchfork's 2017 list of the 200 best albums of the 1960s ranked it at number 12, above Electric Ladyland by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.[52] Ultimate Classic Rock listed it in its unranked Top 100 Albums of the 1960s.[53] Uncut listed it at number 52 on its 200 Greatest Albums of All Time, above Third/Sister Lovers by Big Star but behind Tapestry by Carole King.[54]

Robert Dimery included the album in the 2018 edition of his book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[55]

Reissues

[edit]Along with the group's first three albums, The Velvet Underground received a reissue in 1985.[8][56] These reissues were unexpectedly successful, which led to further releases under PolyGram such as Another View. The album was included in the box set Peel Slowly and See,[56] and would later be reissued as a Super Deluxe edition for its 45th anniversary, including mono versions of tracks, demos, and live performances.[40]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks written by The Velvet Underground (Lou Reed, Doug Yule, Sterling Morrison, Maureen Tucker). All lead vocals by Reed, except where noted. Running times listed are for the Valentin mix; disc one of the 45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition is the Valentin mix.

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Candy Says" | Yule | 4:04 |

| 2. | "What Goes On" | 4:55 | |

| 3. | "Some Kinda Love" | 4:03 | |

| 4. | "Pale Blue Eyes" | 5:41 | |

| 5. | "Jesus" | Reed with Yule | 3:24 |

| Total length: | 22:07 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Beginning to See the Light" | 4:41 | |

| 2. | "I'm Set Free" | 4:08 | |

| 3. | "That's the Story of My Life" | 1:59 | |

| 4. | "The Murder Mystery" | Reed, Morrison, Yule, and Tucker | 8:55 |

| 5. | "After Hours" | Tucker | 2:07 |

| Total length: | 21:50 | ||

Personnel

[edit]The Velvet Underground

- Lou Reed – lead and rhythm guitar, piano; lead vocals except where noted, verse co-vocals on "The Murder Mystery"

- Doug Yule – bass guitar, organ; lead vocals on "Candy Says"; chorus co-vocals on "Jesus" and "The Murder Mystery"; backing vocals

- Sterling Morrison – rhythm and lead guitar; verse co-vocals on "The Murder Mystery"; backing vocals

- Maureen Tucker – percussion; lead vocals on "After Hours"; chorus co-vocals on "The Murder Mystery", backing vocals

Technical personnel

- Dick Smith – art direction

- Angel Balestier – engineer

- Val Valentin – Director of Engineering

- Billy Name – photography

- The Velvet Underground – production

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[57] | Gold | 100,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ Unterberger, Richie (June 1, 2009). White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day. Jawbone Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-906002-22-0.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. December 31, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ Brown, Bill (December 2013). Words and Guitar: A History of Lou Reed's Music. Colossal Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-615-93377-1.

- ^ Deming, Mark. The Velvet Underground - The Velvet Underground (1969) Review at AllMusic. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Unterberger 2017, chpt. 6.

- ^ a b c d Hogan, Peter (1997). The Complete Guide to the Music of the Velvet Underground. London: Omnibus Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-7119-5596-4.

- ^ Hogan 2007, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Unterberger 2017, chpt. 5.

- ^ Jovanovic 2012, p. 131.

- ^ Bockris 1994, pp. 165–168.

- ^ a b c Hogan 2007, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jovanovic 2012, pp. 133–140.

- ^ a b c d Hogan 2007, pp. 250–252.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grow, Kory (November 24, 2014). "Velvet Underground Reflect on Most Profound LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Troy (2001). "The Velvet Underground". In George-Warren, Holly (ed.). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (3rd ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 1035. ISBN 0-7432-0120-5. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-33847-2. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c Kot, Greg (January 12, 1992). "Lou Reed's Recordings: 25 Years Of Path-Breaking Music". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Hermes, Will (December 8, 2015). "The Complete Matrix Tapes". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 16, 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Steve (2006). The A to X of Alternative Music. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 272. ISBN 0-8264-8217-1. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Rathbone, Oregano (March 7, 2021). "The Velvet Underground See The Light On Self-Titled Third Album". uDiscoverMusic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Lapointe, Andrew. "Interview with Doug Yule". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Addicted to Lou". The Village Voice. August 22, 2017. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Sounes, Howard (2015). "A New VU: 1967–8". Notes from The Velvet Underground: The Life of Lou Reed. Great Britain: Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4735-0895-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Bockris & Malanga 1996, pp. 104–110.

- ^ Unterberger 2017, chpt. 4.

- ^ a b Hogan 2007, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Bockris & Malanga 1996, pp. 100–104.

- ^ a b "The Velvet Underground's 'Grey Album' and the Delineation of a Decade, PopMatters". PopMatters. October 29, 2019. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Randy Kennedy (January 8, 2010). "In Search of an Archive of Warhol's Era". The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Heylin 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (July 10, 1969). "Consumer Guide (1)". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1969). "Robert Christgau's 1969 Jazz & Pop Ballot". Jazz & Pop. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "A Basic Record Library: The Fifties and Sixties". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X. Archived from the original on March 12, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Bangs, Lester (May 17, 1969). "The Velvet Underground". Rolling Stone. No. 33. San Francisco. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ Heylin 2005, pp. 119–121.

- ^ "The Velvet Underground [45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition) by The Velvet Underground Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Deming, Mark. "The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ "The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground". Blender. New York. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Velvet Underground". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ a b Berman, Stuart (November 24, 2014). "The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 25, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground". Q. No. 191. London. June 2002. p. 128.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (March 14, 1985). "The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground & Nico / White Light/White Heat / The Velvet Underground / V.U." Rolling Stone. No. 443. New York. Archived from the original on September 7, 2001. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (2004). "The Velvet Underground". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 847–848. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ Weisbard, Eric (1995). "Velvet Underground". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. New York City: Vintage Books. pp. 425–427. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- ^ a b Gensler, Andy (October 28, 2013). "Lou Reed RIP: What If Everyone Who Bought The First Velvet Underground Album Did Start A Band?". Billboard. New York. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1998). "Velvet Underground". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 7 (3rd ed.). Muze UK. pp. 5626–7. ISBN 1-56159-237-4.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 116. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. New York. December 11, 2003.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. New York. May 31, 2012. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "100 Best Albums of All Time". NME. London. March 2003.

- ^ "The 200 Best Albums of the 1960s". Pitchfork. August 22, 2017. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 '60s Rock Albums". Ultimate Classic Rock. March 19, 2015. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "200 Greatest Albums of All Time". Uncut. January 4, 2016.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2018). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-78840-080-0.

- ^ a b Unterberger 2017, chpt. 9.

- ^ "British album certifications – Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Bockris, Victor (1994). Transformer: The Lou Reed Story. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-306-80752-1.

- Bockris, Victor; Malanga, Gerard (1996) [1983]. Up-tight: The Velvet Underground Story. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-0168-6.

- Heylin, Clinton (2005). All Yesterdays' Parties: The Velvet Underground in Print, 1966–1971. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81477-8.

- Hogan, Peter (2007). The Rough Guide to The Velvet Underground. New York: Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84353-588-1. OL 8931815M.

- Jovanovic, Rob (2012). Seeing The Light: Inside The Velvet Underground. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-00014-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (April 23, 2017) [2009]. White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day by Day. London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-81-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Mauro, J-P (April 13, 2018). "The Velvet Underground's earnest prayer: "Jesus"". Aleteia.

External links

[edit]- The Velvet Underground at Discogs (list of releases)