Paul Delaroche

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

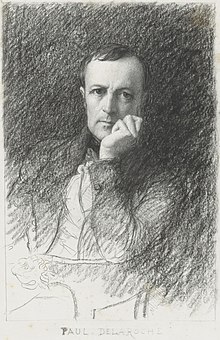

Paul Delaroche | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait | |

| Born | Hippolyte-Paul Delaroche 17 July 1797 Paris, France |

| Died | 4 November 1856 (aged 59) Paris, France |

| Education | École des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) |

| Movement | Romanticism |

| Spouse |

Louise Vernet

(m. 1835; died 1845) |

Hippolyte-Paul Delaroche (French pronunciation: [ipɔlit pɔl dəlaʁɔʃ]; Paris, 17 July 1797 – Paris, 4 November 1856)[1] was a French painter who achieved his greater successes painting historical scenes. He became famous in Europe for his melodramatic depictions that often portrayed subjects from English and French history. The emotions emphasised in Delaroche's paintings appeal to Romanticism while the detail of his work along with the deglorified portrayal of historic figures follow the trends of Academicism and Neoclassicism. Delaroche aimed to depict his subjects and history with pragmatic realism. He did not consider popular ideals and norms in his creations, but rather painted all his subjects in the same light whether they were historical figures like Marie-Antoinette, figures of Christianity, or people of his time like Napoleon Bonaparte. Delaroche was a leading pupil of Antoine-Jean Gros and later mentored a number of notable artists such as Thomas Couture, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Jean-François Millet.

Delaroche was born into a generation that saw the stylistic conflicts between Romanticism and Davidian Classicism. Davidian Classicism was widely accepted and enjoyed by society so as a developing artist at the time of the introduction of Romanticism in Paris, Delaroche found his place between the two movements. Subjects from Delaroche's medieval and sixteenth and seventeenth-century history paintings appealed to Romantics while the accuracy of information along with the highly finished surfaces of his paintings appealed to Academics and Neoclassicism. Delaroche's works completed in the early 1830s most reflected the position he took between the two movements and were admired by contemporary artists of the time—the Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833; National Gallery, London) was the most acclaimed of Delaroche's paintings in its day. Later in the 1830s, Delaroche exhibited the first of his major religious works. His change of subject and "the painting's austere manner" were ill-received by critics and after 1837, he stopped exhibiting his work altogether. At the time of his death in 1856, he was painting a series of four scenes from the Life of the Virgin. Only one work from this series was completed: the Virgin Contemplating the Crown of Thorns.

Biography

[edit]

Delaroche was born in Paris and stayed there for the majority of his life. Most of his works were completed in his studio on Rue Mazarine.[2] His subjects were painted with a firm, solid, smooth surface, which gave an appearance of the highest finish. This texture was the manner of the day[3] and was also found in the works of Vernet, Ary Scheffer, Louis Léopold Robert and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Among his students were Gustave Boulanger, British landscape artist Henry Mark Anthony, British history painters Edward Armitage and Charles Lucy, and American painter/photographer Alfred Boisseau (1823–1901).

The first Delaroche picture exhibited was the large Jehosheba saving Joash (1822).[4] This exhibition led to his acquaintance with Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, with whom he formed the core of a large group of Parisian historical painters. He visited Italy in 1838 and 1843, when his father-in-law, Horace Vernet, was director of the French Academy in Rome.[4][3] In 1845, he was elected into the National Academy of Design, New York, as an Honorary Academician.

Early life

[edit]Paul Delaroche was born into the petty lord de la Roche family, a family of artists, dealers, collectors, and art administrators. His father, Gregoire-Hippolyte Delaroche, was a prominent art dealer in Paris. Paul Delaroche was the second of two sons and was introduced to fine art at a young age. At age nineteen, Delaroche was afforded by his father the opportunity to study at L'École des Beaux-Arts under the instruction of Louis Étienne Watelet. Delaroche was influenced by his father to focus on landscapes while he was at L'École because his brother, Jules-Hippolyte Delaroche, already focused on painting history. After two years at L'École, Delaroche voiced his lack of interest in landscapes and acted on his overall disenchantment with the French academic system by leaving L'École des Beaux-Art in at the end of 1817. The following year he entered the studio of Antoine-Jean Gros where he was able to pursue his greater interest in history painting.[5]

Artistic independence

[edit]Delaroche's debuted at the Salon of 1822 where he exhibited Christ Descended from the Cross (1822: Paris, Pal. Royale, Chapelle) and Jehosheba Saving Joash (1822; Troyes, Mus. B.-A. & Archéol). The latter was a product of Gros's influence and was praised by Géricault who supported the beginning of Romanticism. The schooling Delaroche received at L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts tied him to the ideas of Academicism and Neo-Classicism while his time spent in the studio of Gros aroused his interest in history and its representation through Romanticism. His painting, Joan of Arc in Prison (1824; Rouen, Mus. B.-A.), which was exhibited in the Salon of 1824, along with his following works reflect the middle ground he occupied. Delaroche studied the recent tradition of English history painting at the time, which he incorporated into his own productions. In 1828 he exhibited the first of his English history paintings, Death of Queen Elizabeth. Delaroche's focus on English history brought him popularity in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s. In the 1830s, he produced some of his most lauded works, including Cromwell Gazing at the Body of Charles I (1831. Mus. B.-A., Nîmes), The Princes in the Tower (1831, Louvre, Paris) and his most acclaimed piece, the Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833, NG, London). Recognizing his talent and popularity, the Académie des Beaux-Arts elected Delaroche a member of the society in 1832. A year following, he became a professor at L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The same year, he was commissioned to paint a large mural at the central nave of L'Église de la Madeleine in Paris. Delaroche recognized his lack of experience in religious painting and so travelled for one year in Italy to educate himself on the religious works of the past. Upon his return to France, he was told he was to work with Jules-Claude Ziegler, but abandoned the project altogether thinking that Ziegler would soil the image he already had in mind. In 1837 he exhibited St. Cecilia (1836; London, V&A), which was the first of his significant religious paintings. Delaroche's change of subject was less impressive to French critics than his previous works.

As a history painter, Delaroche aimed to present in his work a "philosophical analysis" of a historical event and link it to "the nineteenth-century understanding of historical truth and historical time." Although there are some discrepancies between history and his own history painting, Delaroche saw the importance in being faithful to the presentation of facts. German literary critic, Heinrich Heine, says "[Delaroche] has no great predilection for the past in itself, but for its representation, for the illustration of spirit, and for writing history in colours." Delaroche painted all of his subjects in the same light whether they were great historical figures from the past, founders of Christianity, or important political figures of his time like Marie Antoinette or Napoleon Bonaparte. He carefully researched the costumes and accessories and settings he included in his paintings in order to accurately present his subject. To accentuate historical accuracy, Delaroche painted with meticulous detail and finished his paintings with clear contours. The varying movement of his brush strokes along with the colors and placement of his subjects give each of them a unique appearance and allows them to act in the spirit and tone of their character and the event. The public eye is less observant of fine details and nuances in painting, but Delaroche appreciated the literary value of his paintings over their pictorial value. He balances the literary aspects with the theatricality, narrativity, and visuality of his historical paintings.

Historical works and accuracy

[edit]His dramatic paintings include Strafford Led to Execution, depicting the English Archbishop Laud stretching his arms out of the small high window of his cell to bless Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, as Strafford passes along the corridor to be executed, and the Assassination of the duc de Guise at Blois. Another famous work shows Cardinal Richelieu in a gorgeous barge, preceding the boat carrying Cinq-Mars and De Thou to their execution. Other important Delaroche works include The Princes in the Tower and La Jeune Martyre (showing a young female martyr floating dead on the Tiber).[3]

Delaroche's work sometimes contained historical inaccuracies. Cromwell lifting the Coffin-lid and looking at the Body of Charles is based on an urban legend. He tended to care more about dramatic effect than historical truth: see also The King in the Guardroom, where villainous Puritan soldiers blow tobacco smoke in the face of King Charles, and Queen Elizabeth Dying on the Ground.

Later works and the close of his career

[edit]After 1837, Delaroche stopped exhibiting his work altogether. The disappointing public reception of his painting, St. Cecilia, along with his overall rejection of Davidian values in French society and government led him to his "self-imposed exile from the government-sponsored Salons." Delaroche then commenced the creation of his most famous work, The Hemicycle, painted on a semicircular saloon at L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The Hemicycle was a 27-meter panoramic that included over seventy of the most famous artists since Antiquity. The artists included represent Gothic, Greek, Roman, and Renaissance art. The subjects of this painting appeal to the academic taste of the nineteenth-century. Delaroche painted with encaustic mixtures to create this monumental piece—a technique in which pigment is mixed with hot wax and painted onto the plaster to create a smooth surface. Delaroche did not complete this project alone; four of his students assisted him and together they worked from 1837 to 1841. In 1855 the work was severely damage by fire and Delaroche spent the last year of his life restoring his work. Delaroche died in 1856 and restoration was taken over by Tony Robert-Fleury, a student of Delaroche.

Marriage to Louise Vernet

[edit]

Delaroche's love for Horace Vernet's daughter Louise was the absorbing passion of his life. He married Louise in 1835, in which year he also exhibited Head of an Angel, which was based on a study of her. It is said that Delaroche never recovered from the shock of her death in 1845 at the age of 31. After her loss he produced a sequence of small elaborate pictures of incidents in Jesus's Passion.[3] He focused attention on the human drama of the Passion, as in a painting where Mary and the apostles hear the crowd cheering Jesus on the Via Dolorosa, and another where St. John escorts Mary home after her son's death.

The Hémicycle

[edit]-

Section 2 of the Hémicycle, 1841–1842

-

Central section of the Hémicycle, 1841–1842

-

Section 3 of the Hémicycle, 1841–1842

In 1837, Delaroche received the commission for the great picture that came to be known as the Hémicycle, a Raphaelesque tableau influenced by The School of Athens. This was a mural 27 metres (88.5 ft) long, in the hemicycle of the award theatre of the École des Beaux Arts. The commission came from the École's architect, Félix Duban. The painting represents seventy-five great artists of all ages, in conversation, assembled in groups on either hand of a central elevation of white marble steps, on the topmost of which are three thrones filled by the creators of the Parthenon:[6] sculptor Phidias, architect Ictinus, and painter Apelles, symbolizing the unity of these arts.

To supply the female element in this vast composition he introduced the genii or muses, who symbolize or reign over the arts, leaning against the balustrade of the steps, depicted as idealized female figures.[6] The painting is not fresco but done directly on the wall in oil. Delaroche finished the work in 1841, but it was considerably damaged by a fire in 1855. He immediately set about trying to re-paint and restore the work, but died on 4 November 1856, before he had accomplished much of this. The restoration was finished by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury.

Fake or Fortune

[edit]In 2016, the BBC TV programme Fake or Fortune? investigated the authenticity of a version of Delaroche's Saint Amelia, Queen of Hungary. After reviewing the show's findings, Professor Stephen Bann, a leading Delaroche expert, concluded that the version, bought for £500 in 1989 by the late art collector and dealer Neil Wilson, and housed at Castle of Park in Cornhill, Aberdeenshire, was in fact the lost original.[7] Wilson's widow, Becky, was reported to have decided to keep the painting, but allow it to go on display at the British Museum in London when a Delaroche exhibition takes place.[8] Subsequently, the painting was sold via Christie's in July 2019 for £33,750.[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

Saint Vincent de Paul Preaching to the Court of Louis XIII, 1823

-

Joan of Arc, Sick, Interrogated in Prison by the Cardinal of Winchester, 1824, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, France.

-

The Death of Elizabeth I, Queen of England, 1828, Louvre

-

The Duke of Angoulême at the Taking of Trocadero, 1828, Versailles

-

The Children of Edward, 1830, Louvre

-

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, 1833, National Gallery, London

-

Strafford led to Execution, 1836

-

Charles I Insulted by Cromwell's Soldiers, 1836, thought lost in The Blitz, rediscovered in 2009

-

Peter the Great, 1838

-

Napoleon abdicating at Fontainebleau, 1845, The Royal Collection, London

-

Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1850, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool[10]

-

The Young Martyr (1855)

Photography

[edit]Delaroche is often quoted as saying "from today, painting is dead." The observation was probably made in 1839, when Delaroche saw examples of the Daguerreotype, the first successful photographic process.[11]

See also

[edit]- Charles I Insulted by Cromwell's Soldiers, the 1836 Delaroche painting thought lost in the Blitz, rediscovered in 2009.

References

[edit]- ^ "Wallace Collection Online - Delaroche Hippolyte (Paul) Delaroche". wallacelive.wallacecollection.org. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Hippolyte Delaroche (Paul Delaroche), French painter (1797-1856)". www.1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Scott 1911, p. 944.

- ^ a b "Paul Delaroche". Encyclopedia of Visual Artists. visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Paul Delaroche 1797-1856". The National Gallery. The National Gallery (London). Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ a b Scott 1911, p. 945.

- ^ Muñoz-Alonso, Lorena (25 July 2016). "Long-Lost Panting by French Master Paul Delaroche Authenticated on TV Show". artnet News. Artnet Worldwide Corporation. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Davidson, Peter (26 July 2016). "Late North-East Art Dealer's £500 Artwork Revealed to be Rare Masterpiece". Evening Express (Aberdeen). Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Sainte Amélie, Reine de Hongrie – Christie’s.

- ^ "Artwork details, Liverpool museums". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk.

- ^ Bann 1997, p. 17.

Sources

[edit]- Bann, Stephen. 1997. Paul Delaroche: History Painted. London: Reaktion Books; Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01745-X

- Bann, Stephen. 2006. "Paul Delaroche's Early Work in the Context of English History Painting." Oxford Art Journal, 2006. 341.

- Bann, Stephen and Linda Whiteley. 2010. Painting History: Delaroche and Lady Jane Grey. London: National Gallery Company; Distributed by Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-85709-479-4

- Carrier, David. Nineteenth-Century French Studies 26, no. 3/4 (1998): 476–78. JSTOR 23537629

- Chilvers, Ian. "Delaroche, Paul." In the Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-687.

- Deines, Stefan, Stephan Jaeger, and Ansgar Nünning. 2003. Historisierte Subjekte—subjektivierte Historie: zur Verfügbarkeit und Unverfügbarkeit von Geschichte. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Duffy, Stephen. "Delaroche and Lady Jane Grey: London." The Burlington Magazine 152, no. 1286 (2010): 338–39. JSTOR 27823182.

- Jordan, Marc. "Delaroche, Paul." The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 17 November 2016, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t118/e711.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Scott, William Bell (1911). "Delaroche, Hippolyte". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 944–945.

- Tanyol, Derin. (2000) Histoire anecdotique—the people's history? Gras and Delaroche, Word & Image, 16:1, 7–30, doi:10.1080/02666286.2000.10434302

- Whiteley, Linda. "Delaroche." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 4 November 2016, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T021935pg2.

- Wright, Beth S. "The Space of Time: Delaroche's Depiction of Modern Historical Narrative." Nineteenth-Century French Studies 36, no. 1/2 (2007): 72–93. JSTOR 23538480.

- Chernysheva, Maria. "Paul Delaroche: The Reception of his Work in Russia." Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 9, no. 3 (2019): 577–589.

External links

[edit]- Delaroche returned after 70 years

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . . 1914.

- 1797 births

- 1856 deaths

- French romantic painters

- Painters from Paris

- Academic art

- Members of the Académie des beaux-arts

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Pupils of Antoine-Jean Gros

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- 19th-century painters of historical subjects

- 19th-century French male artists

![Herodias [fr], 1843, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, Germany.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Herodias_with_the_Head_of_St._John_the_Baptist_-_Paul_Delaroche_-_Wallraf-Richartz_Museum_-_Cologne_-_Germany_2017.jpg/222px-Herodias_with_the_Head_of_St._John_the_Baptist_-_Paul_Delaroche_-_Wallraf-Richartz_Museum_-_Cologne_-_Germany_2017.jpg)

![Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1850, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Paul_Delaroche_-_Napoleon_Crossing_the_Alps_-_Google_Art_Project_2.jpg/233px-Paul_Delaroche_-_Napoleon_Crossing_the_Alps_-_Google_Art_Project_2.jpg)